McCain: Mr. Uncongeniality « The Washington Independent

Jul 31, 2020798.9K Shares12.1M Views

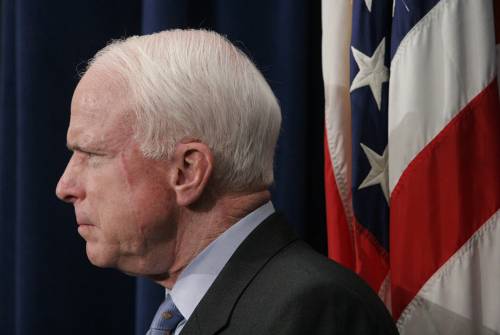

Sen. John McCain (WDCpix)

PHOENIX—When you talk to current and former members of Arizona’s congressional delegation about Sen. John McCain’s legislative style, one element runs through all the accounts — the Republican presidential nominee’s combustible temper.

McCain’s often-cited outbursts are a hallmark of his career, but what triggers them is subject to debate. Some former Democratic colleagues and non-political observers say McCain’s ego is easily bruised; and when that happens, the result can be explosive rage. Republican supporters, however, say that what many describe as “rage” is McCain’s passion to fight for what he believes is right — particularly when defending the downtrodden.

McCain’s Senate office and his presidential campaign office did not respond to a repeated telephone calls and email queries for comment.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Former Sen. Dennis DeConcini, a Democrat who represented Arizona from 1977-95, says, for example, that the GOP presidential nominee does not take criticism well. “[McCain] has a terrible time with anybody questioning his judgment,” said DeConcini, “If you cannot accept somebody questioning your judgment, whether it is to invade Iran or impose sanctions on Russia, how can you come to sound conclusions for the national interest?”

Rep. John Shadegg (R- Ariz.) sees McCain’s reputed sensitivity to criticism differently. “He’s intense, he’s passionate,” Shadegg said. “That’s what has always caused me to admire him” — and that’s what makes him a great leader.

Shadegg doesn’t dispute McCain’s fiery nature, but insists McCain’s temperament doesn’t stop him from consulting a wide range of opinion before making major decisions. “He’ll give your argument thoughtful consideration,” said Shadegg, who has represented Arizona’s 3rd Congressional District since 1994 and is considered to be in the toughest reelection race of his career.

McCain is most likely to factor in differing opinions when it comes to matters affecting Arizona, many former Arizona congressmen say, especially if he is not well versed in those issues. The Grand Canyon state, they insist, has always been of secondary interest to McCain.

“John McCain was a national senator from the very beginning, and he didn’t give much attention to Arizona issues,” said retired GOP Rep. Jim Kolbe, now a fellow at the German Marshall Fund. “But when he did get involved, it was at a level that he really knew and understood the issues. On immigration reform, he was deeply involved.”

On legislative matters important to Arizona, McCain typically defers to his fellow GOP senator, Jon Kyl, according to former Rep. Matt Salmon. A Republican, Salmon served in the House from 1994-2000 before narrowly losing to Democrat Janet Napolitano in the 2002 governor’s race.

“He acknowledged on certain issues that Jon Kyl was more the expert,” said Salmon, now president of Competitive Telecommunications Assn., an industry trade group, “If he was dealing with military issues and Indian affairs, John usually took more of the lead.”

One former GOP congressman, who asked to speak off the record, said that McCain “carefully picked what he wanted to get involved with.” As the congressman describes it, “He had bigger fish to fry.”

Former Sen. Dennis DeConcini (Wikimedia)

DeConcini’s harsh appraisal of McCain perhaps stems, at least in part, from their time as part of the infamous Keating Five. DeConcini believes McCain leaked confidential documents in an attempt to damage him before the Senate Ethics Committee’s 1990-91 hearings into the five senators’ role in seeking banking regulatory relief for financier Charles H. Keating Jr. McCain has denied under oath that he leaked the documents.

In the fall of 1989, a number of confidential Ethics Committee documents were leaked to major newspapers, including the New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and The Arizona Republic, that portrayed DeConcini and the Democrats Don Riegle of Michigan and Alan Cranston of California as the most culpable of the senators. In September 1990, The New York Times, citing “congressional sources,” reported that the committee’s investigator, Robert M. Bennett, had confidentially recommended to the panel that Sen. John Glenn of Ohio and McCain be cleared.

A 1992 investigation into the leaks by special prosecutor Peter Fleming found circumstantial evidence of McCain’s role. “Sen. McCain, his staff, as well as his counsel all deny that they knew Bennett’s recommendation. These denials are contradicted by the evidence,” Fleming wrote in his report. However, he continued, “there is no direct evidence to show that McCain made the disclosures to The New York Times.”

The Boston Globe reported in 2000 that an earlier GAO investigation had found overwhelming circumstantial evidence that McCain was involved in the leaks. Clark B. Hall, a former FBI agent, told The Globe that McCain lost his temper during his interview about the leaks. “His reaction that day was to point the finger at others,” Hall said, “He said I ought to look at DeConcini, I ought to look at Riegle.” Hall said that he found McCain’s finger-pointing “contemptible” and “consistent with the leaks themselves, which were intended to shift the blame elsewhere.”

Hall told The Globe that the ethics committee ignored the evidence implicating McCain. The panel, he said, “smoothed it over.”

In the larger matter of whether McCain had acted improperly, the committee ruled that McCain exercised “poor judgment.” DeConcini was found to have given the “appearance of being improper.”

DeConcini, who served with McCain during the Vietnam War hero’s first 12 years in Congress, claims to “know McCain well.” He said McCain is prone to viewing criticism of his ideas as an attack on his patriotism as well as a personal affront. When McCain does defer to others, “he becomes somewhat erratic,” DeConcini said, “like his recent handling of economic issues.”

McCain’s thin skin became evident early in his Senate career, according to DeConcini. He recalled an incident when McCain voted against a bill DeConcini sponsored. DeConcini made derogatory comments about McCain’s vote, and “he just laid into me on the floor of the Senate, saying ‘How dare you begrudge my name?’ I just walked away.”

Other senators developed different tactics to deal with McCain’s temper. One time, DeConcini said, McCain was upset that Sen. Timothy Wirth, a Democrat from Colorado, refused to move to the Senate floor a bill that both McCain and DeConcini supported.

“McCain started putting his finger into Wirth’s chest,” demanding that Wirth allow the bill to move forward, DeConcini recalled. Wirth responded by getting into McCain’s face, whereupon he “calmed down.”

DeConcini said that Wirth later told him that House members had learned to use this in-your-face tactic when McCain, who served in the lower chamber from 1982-1986, lost his cool. “Whenever John blows up, you move in close to him,” DeConcini said Wirth told him. “He can’t take it.”

Shadegg sees a noble motive behind McCain’s forceful tactics. “He doesn’t like to see the little guy get hurt by big powerful interests.”

Shadegg cites McCain’s investigation of lobbyist Jack Abramoff as an example of McCain’s willingness to go up against powerful interests — even those with close ties to the GOP. “John McCain didn’t give a damn about the fact that he was going after a Republican,” Shadegg said. “He was fighting for what he saw as an injustice.”

McCain was chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee from 2005-2007 and led an investigation into Abramoff’s dealings with Indian tribes and development of casinos. The committee investigation was parallel to a federal criminal probe that led to Abramhoff pleading guilty to three federal counts of mail fraud, conspiracy and tax evasion. Abramoff was sentenced in September to four years in prison. He was already serving a six-year sentence on state charges from Florida.

McCain’s willingness to fight a pitched battle across ideological or party lines has cost him dearly with conservatives, many of whom remain lukewarm about his presidential run. “To the frustration of some Republicans,” Shadegg said, “he doesn’t have a ‘Republican’ or a ‘conservative’ filter. He has a ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ filter.”

Pat Murphy, the former publisher and editor of The Arizona Republic, has closely followed McCain’s political career from its start in 1982. Now retired and living in Idaho, he was one of few Arizona journalists with a record of taking on McCain. His newspaper paid for it. For months at a time, McCain would not talk to the state’s largest daily newspaper.

Murphy said McCain liked to attach himself to causes that would attract attention, rather than doing the work of delving deeply into complex legislation that might effect Arizona — like water rights and mining reform.

“He had his ear turned to issues he could exploit and capitalize on,” Murphy said. Campaign-finance reform and going after certain high-profile defense contracts generated a lot of attention for McCain, Murphy said.

Murphy, a Democrat, disputes the idea that McCain’s irascible temperament should be overlooked because his primary interest is serving his country. “He doesn’t give a crap about the country,” Murphy claims. “It’s all about John McCain.”

Paolo Reyna

Reviewer

Paolo Reyna is a writer and storyteller with a wide range of interests. He graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies.

Paolo enjoys writing about celebrity culture, gaming, visual arts, and events. He has a keen eye for trends in popular culture and an enthusiasm for exploring new ideas. Paolo's writing aims to inform and entertain while providing fresh perspectives on the topics that interest him most.

In his free time, he loves to travel, watch films, read books, and socialize with friends.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles