A $50-Billion Warship Mystery

While costly, the ship was the linchpin in the sea service’s advanced strategy to patrol and fight in the most dangerous shallow sea lanes, known as littorals. Think Iraq’s national waters, where the country’s two oil terminals are located. But the Navy suddenly killed the weapon program. The explanation has pleased no one -- especially Congress.

Jul 31, 20206.7K Shares1.6M Views

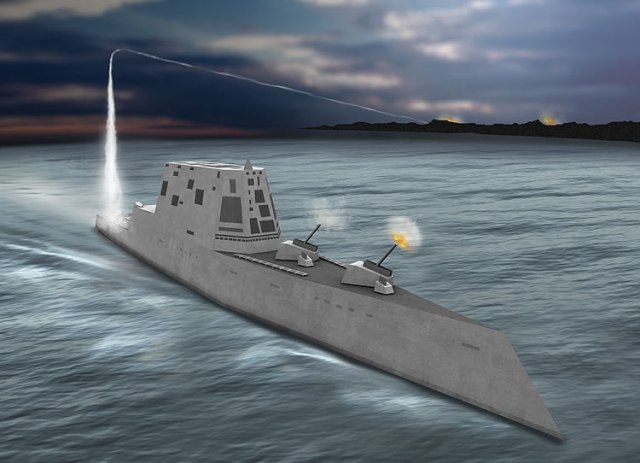

The DDG-1000 Zumwalt (navy.mil)

There was tension in the House of Representatives hearing room July 31 as Rep. Gene Taylor (D-Miss.) called to order a meeting of the Seapower and Expeditionary Forces subcommittee. “This may very well be the most important hearing this subcommittee has held since our hearing last January on the procurement of Mine-Resistant Ambush-Protected vehicles,” Taylor said.

The MRAPs he referred to are specialized armored vehicles designed to protect U.S. troops from roadside bombs in Iraq, the biggest killer of Americans. Since 2006, the Pentagon has spent more than $10 billion in a rush to buy the 15-ton vehicles, which have reportedly saved scores of American lives.

The subject of the July hearing — the topic that had Taylor and his fellow committee members on edge — was a multibillion-dollar warship program that was an order of magnitude more complex than MRAP, five times as expensive and potentially as important. It’s called the DDG-1000 Zumwalt, a ship class that the Navy had hailed as the linchpin of a new military strategy.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

But after more than a decade of development at a cost of billions of dollars, the Navy announced in July that it no longer wanted the new ship. Problem was, the sea service couldn’t come up with a coherent reason why.

The decision on DDG-1000 had come out of the blue. And it turned upside down the Navy’s expensive, delicate plans to boost the size of its fleet and improve its ability to operate close to resource-rich, heavily populated shorelines.

The decision sparked protests from shipyards and defense contractors that had started building DDG-1000s. The munitions industry looked to Congress for an explanation — but Congress had none to offer. The decision to kill the new destroyer had been made without consultation with elected representatives. Even now, five months later, the Navy’s rationale for ending the $50-billion DDG-1000 program seems full of contradictions, casting doubt on the Navy’s ability to manage complex weapons buys at a time when the financial crisis and a new administration might force defense budgets to shrink.

**A Departure for the Navy **

The new destroyer was intended to protect U.S. sailors fighting in the world’s most dangerous sea zones — shallow, rocky, near-shore waters called “littorals.”

The world’s littorals are rich in resources and home to a growing portion of the world’s population. Patrolling and fighting in littorals pose unique dangers. The water is shallow and turbulent, and the proximity to shore means warships can be threatened by land-based weapons and short-range high-speed boats.

Traditionally, the U.S. Navy has kept to deep waters — where big, expensive ships are safe from land-based threats and free to maneuver without risk of running aground. The Navy designed its ships to suit the deep.

That began to change in 1994, when the sea service launched the $10-billion design effort for the DDG-1000 Zumwalt. By 2006, it was time to build the first one, and the Navy had to tell congressional budgeters how many it wanted.

With the per-vessel cost projected to exceed $3 billion — and possibly reach $5 billion, according to one estimate — the Navy decided it could afford only seven DDG-1000s. Congress approved the plans and funded construction of the first two ships.

Then this year the Navy announced it wanted to buy only the two previously funded Zumwalts and cancel the other five. It was the first major shipbuilding decision by the Navy’s new top officer, Adm. Gary Roughead, who had taken command in 2007. It was a big one — an acquisitions program nearly 15 years in the making was scuttled.

Naval shipyards and other defense contractors were out tens of billions of dollars in projected revenue. And Congress — Taylor’s powerful subcommittee, particularly — was caught in the middle, befuddled by the reversal and left holding the purse strings for a Navy strategy that, suddenly, seemed to lack direction.

To be sure, the Navy had an alternate plan. In the place of the axed DDG-1000s, the sea service said it wanted to buy up to 12 more of its older destroyer class, the DDG-51 Arleigh Burke. The Navy has 62 Burkes in service or on order.

While the Navy’s announcement came as a surprise to elected officials and industry representatives, there also were strong arguments to ditch the destroyer. Zumwalt is expensive, with a per-ship price potentially exceeding $4 billion, not counting R&D. The most recent Burkes, by contrast, cost around $2.2 billion apiece, again not counting R&D (most of which was completed in the 1990s).

The Navy now has roughly 280 front-line ships and wants to boost that number to 313 in about 15 years by buying more than a dozen ships a year — double the average rate in the 1990s and early 2000s. Squeezing more ships out of the roughly $20-billion-a-year shipbuilding budget is therefore critical.

In that context, the DDG-1000 costs “a lot of money,” Vice Adm. Barry McCullough, the Navy’s top technologist, testified in March before Taylor’s subcommittee.

A Startling Admission

But when McCullough testified at Taylor’s July hearing, he said little about cost. Now the Navy was killing off its new destroyer project because the ship “cannot perform area air defense; specifically, it cannot successfully employ the Standard Missile-2, SM-3 or SM-6, and is incapable of conducting Ballistic Missile Defense,” McCullough said.

This was a big deal. Recent classified naval studies had found what McCullough called “increased war-fighting gaps, particularly in the area of integrated air- and missile-defense capability,” against ballistic missiles similar to ones that China could fire and against small cruise missiles like those used by the terror group Hezbollah against the Israeli Navy in the 2006 Lebanon war. Both missile types are particularly dangerous in near-shore waters.

As wonky as such technical details might sound, jaws practically dropped when McCullough made the assertion about the Zumwalt and its missile capability. For good reason. As recently as March, the Navy had stated — on the record — that Zumwalt was better at air defense than any other warship and less vulnerable in shallow waters.

McCullough’s pronouncement represented a startling — and, to some, seemingly absurd — 180-degree turn on a program costing as much as $50 billion over two decades.

Bigger Questions

The Zumwalt decision immediately raised questions about the Navy’s ability to plan, execute and rationalize complex weapons programs. There are indications that the shuffle is driven as much by the obscure preferences of the Navy’s top officer as by any careful analysis of U.S. defense needs.

“This whole thing is very strange,” Sen. Susan Collins (R-Me.) said after hearing about the proposed Zumwalt cuts. Collins, a reliable Navy booster, counts one of the nation’s biggest shipyards in her constituency. She said she had not seen any documentation justifying the Navy’s sudden decision.

Neither had the chief Pentagon weapons buyer, John Young. He called the announcement “a little unusual” and said the Navy needed to do more analysis of the potential costs and benefits of a switch.

At least one firm involved in designing and building DDG-1000s is equally perplexed. “It doesn’t make sense,” Dan Smith, a vice president at Raytheon, told The Washington Independent. Raytheon makes Zumwalt’s radars. Smith said that “the pieces were all there” to make the Zumwalt class capable of using all the Navy’s missiles — and even using them better than any other warship, with just a little extra cash.

Smith said that for Zumwalt to fire SM-2s, the Navy needs only to fund the completion of an electronic data-link that allows the missile and the ship’s S-band radar to “talk” to each other. The Navy said that data-link would cost $80 million. With that addition, the DDG-1000 would be as capable as a DDG-51, which also has an S-band radar, Smith said. Indeed, the two ships’ weapons systems would be nearly identical.

With an extra few hundred million — “three times” the cost of the data-link, according to Smith — the Navy could link SM-2 missiles to the DDG-1000’s second radar, a futuristic X-band system, making the vessel an even better “air defender” than the DDG-51.

Smith’s claims weren’t the empty promises of a salesman. As late as March, Capt. Jim Syring, the Navy’s DDG-1000 program manager, was giving briefings that cited DDG-1000’s “significant capability improvements in every warfare area vs. DDG-51” — including air defense using Standard missiles.

As for Ballistic Missile Defense, Smith said it would cost $550 million to do the R&D to give Zumwalt BMD capability, plus $110 million per ship outfitted. That cost is consistent with an Navy plan to add BMD capability to 18 older ships, including DDG-51s, for a total of $1.2 billion, not counting R&D.

So if DDG-1000 really is as capable as DDG-51, if not more so, why did the Navy use capability as a rationale for axing Zumwalts? Smith said he doesn’t know. “They don’t connect,” he said of the Navy’s tactics for justifying shipbuilding decisions. Reached for comment, a Navy spokesman only repeated the major points of McCollough’s controversial July testimony.

To be sure, even if the upgrades for air- and missile-defense for the DDG-1000 are relatively affordable, the total vessel — including special long-range guns and a radar-deflecting hull — is pricey. For that reason, the Navy’s decision to curtail the program “made perfect sense,” according to Bob Work, an analyst with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment. But the sea service “kind of gooned up selling” its destroyer plans to Congress, Work told The Washington Independent.

The “gooned-up” salesmanship belies a year-long campaign by Chief of Naval Operations Roughead to end the Zumwalt program, sources say. Roughead apparently opposed the DDG-1000 when he took over the Navy’s top position last September. He soon began chipping away at support for the program. That meant dealing with four key Zumwalt supporters: Dep. Defense Sec. Gordon England;Pentagon acquisitions chief Young; Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen; and Rear Adm. Charles Goddard, then the Navy’s top shipbuilder.

England, Young and Mullen are all senior to Roughead: changing their minds was a delicate process. “Behind scenes,” Work says, “Roughead was trying to convince those guys they made a bad decision” regarding plans to buy seven Zumwalts. In time, he succeeded.

The fourth key supporter, Goddard, was relieved of command for allegedly mistreating women while drunk during official travel. The path was clear for Roughead to end the DDG-1000 and switch to a vessel he preferred — the tried-and-true DDG-51.

Does the Navy Have a Littoral Strategy?

But if DDG-1000 issuperior to DDG-51 in shallow waters, as the evidence indicates, does the switch to the older warship represent a shift in the Navy’s littoral strategy. In abandoning its potentially most powerful littoral warships, is the Navy actually abandoning littoral warfare?

The consequences of such a move would be enormous. After all, the Navy’s own Maritime Strategy, published last year, emphasized that “lifeblood” global trade “relies on free transit through increasingly urbanized littoral regions.”

The world’s littorals include Iraq’s national waters, a heavily trafficked area where the country’s only two oil terminals are located, and resource-rich Somali waters infested with hundreds of heavily armed pirates riding in speedboats. The Navy currently has only a handful of ships capable of maneuvering around the terminals or chasing pirates close to land. Under plans finalized in 2006, the Navy would have bought more than 60 new littoral warships — 55 lightweight “Littoral Combat Ships” plus seven of the heavier DDG-1000s.

Since the plans were developed, cost overruns on the LCS prompted Congress to cancel three of the first seven. Combined with LCS’s problems, the recent cuts to DDG-1000 might represent a gutting of the future littoral fleet at a time when near-shore threats are growing.

With anti-ship missiles, small gunboats and sea mines proliferating in littoral zones, the Navy seems to have decided to pull back its amphibious vessels, which carry Marines, and keep them at least 25 miles from shore, Gen. James Conway, Marine Corps commandant, said in September. The littorals are just too dangerous for existing Navy ships and their crews.

Without the right warships, the Navy might never “re-take” shallow waters. In that sense, the DDG-1000 perhaps occupies a similar position as other expensive weapons systems — like the bomb-resistant MRAP trucks — whose urgency trumps price.

Nonetheless, under Roughead’s leadership, the Navy does appear to be abandoning its littoral ambitions, as much for cost reasons as anything else. This despite the Maritime Strategy’s promise that “we will not permit conditions under which our maritime forces would be impeded from freedom of maneuver and freedom of access.” The mysterious destroyer shuffle that (publicly) started in July appears to be both a cause and a consequence of the littoral retreat.

But with a new administration about to take office in January, that might change. The Navy can only propose shipbuilding changes: Congress and the president hold the purse strings. Already, Congress has pressured the Navy to add back one of the canceled DDG-1000s, for an eventual total of three. The new administration might restore more.

“Anything could happen,” Work says.

David Axe is the author of “Army 101: Inside ROTC in a Time of War.” He blogs at www.warisboring.com.

Camilo Wood

Reviewer

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles