Foreclosure Machine Grinds On Through Holiday Season

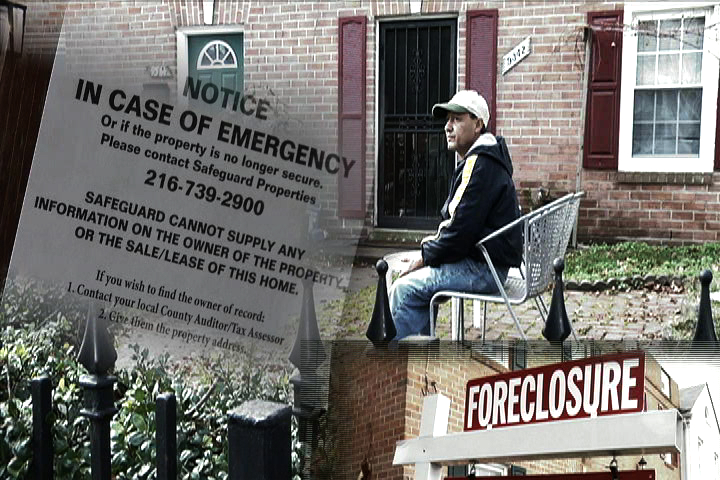

Foreclosures were supposed to pause between Thanksgiving and the new year, but for hundreds of thousands of homeowners, like Julio Angulo of suburban Virginia, they still face losing their homes this month.

Jul 31, 2020202.6K Shares4.7M Views

This is supposed to be the season for a break in home foreclosures, a pause in evictions over the holidays.

But it’s not working out that way for everyone. And certainly not for Julio Angulo of suburban Virginia, another victim of a foreclosure machine that seems to be almost unstoppable.

To great fanfare, mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac announcedlast month they would temporarily halt foreclosures and evictions from Thanksgiving to Jan. 9. One analyst calledthe move “a giant timeout” to help people stay in their homes while they try to get their loans modified. The decision also avoids the spectacle of two government-controlled finance companies throwing families out on the street at Christmas time.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Days before, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac unveiled a major rescue plan to streamlinemodifications of loans to make them more affordable for potentially hundreds of thousands of borrowers. Banks including JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America also suspended foreclosures while tryingto restructure troubled homeowner loans.

And Monday, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson said for the first time that he would considerusing money from the $700-billion Troubled Asset Relief Program to help avoid foreclosures.

But nothing seems to shut down the foreclosure machine — at least so far.

Fannie’s and Freddie’s holiday program, for example, applies only to new foreclosures, not those already in the pipeline, which is full. Some 765,558 properties received default notices, or were foreclosed on, during the third quarter, a new record, RealtyTrac figures show. And while the two mortgage giants together own or guarantee $5 trillion of the nation’s mortgages, they don’t hold most of the riskiest subprime loans at the heart of the housing crisis. That means their suspension program is likely to affectonly a small percentage of homeowners facing foreclosure.

So on a chilly Monday morning in December, at a complexof several hundred modestly priced townhomes in a working-class area of the city of Manassas in suburban Virginia, it was business as usual. Another foreclosed house. An eviction, yet again. One more former homeowner, saying goodbye.

At 8:40, realtor Keith Elliott Jr.was shuffling through paperwork in his car parked outside a three-level brick townhouse with maroon shutters that was scheduled for a lockout eviction. The owner apparently had refused to leave the premises despite getting a foreclosure notice.

Elliott represents the mortgage company, Aurora Loan Services,and has the job of securing the property after the eviction. He explained that Julio Angulo bought the townhouse in 2005 for $280,000, a price that reflected the peak of the housing boom. The property now is assessed at $225,300.

On July 8, Aurora foreclosed on the house. Shortly after that, Elliot visited the property and made Angulo a $1,500 “cash for keys”offer if he left the property within two weeks, and it was in good condition. Angulo spurned the offer, Elliott said.

During his visit, Elliot said he noticed that the three bedrooms upstairs had key locks, a sign the owner was renting them out.

On this December morning, Elliott was waiting for a contractor from a property management company to show up to change the locks. He was in a somber mood.

“This is one aspect of my job,” Elliott said, “that really does suck.”

At 9:17, Fernando Alves, the locksmith for Safeguard Propertiespulled up in his truck. He greeted Elliott, then waited for the sheriff.

Prince William County Sheriff’s Deputy J.M. Zampinoarrived some 20 minutes later. He bounded out of his car and walked to the front door of the townhouse. Five sharp knocks followed. “Sheriff’s office,” he bellowed. “Hello?”

Zampino noticed keys hanging from the door knocker. “Looks like someone left some keys for us,” he said.

He unlocked the door and pushed it open.

Standing in from of him was Angulo, 55, wearing blue jeans, a jacket and a baseball cap with an inscription that read “60th Annual Greater Manassas Christmas Parade.”

“How are you doing, sir?” Zampino asked. He explained he was a deputy sheriff.

“I’m waiting for a friend of mine to help me move,” Angulo replied in a soft voice. “Can I have time? How long can I stay here?”

Zampino stepped inside and began to look around, with Angulo following him. The two continued talking. Zampino turned toward the door and announced to Elliot and Alves the locksmith that only Angulo was inside the house. Angulo slowly trailed Zampino as he headed upstairs. “I broke my knee,” he told him.

“You broke your knee? Oh boy,” Zampino replied, sympathetically.

With Zampino and Angulo inside, Alves drilled away to remove the front-door lock and replace it with a new deadlock. He was done in a flash — by 9:42.

Despite the loud drilling noise and the presence of a sherriff’s car outside, neighbors hardly gave the townhouse a second look as they walked by. About half of the 67 properties listed for sale in the complex, called Georgetown South, are foreclosures, Elliott said. Vacant properties with foreclosure signs in front of them sit adjacent to homes with lawns brightly decorated for Christmas.

At 9:44, 10 minutes after arriving, Zampino finished his inspection of the house and stepped outside.

Zampino’s job has taken its toll on some law-enforcement officers. In Cook County, Ill., the sheriff recently refusedto evict renters from foreclosed homes in a Chicago neighborhood, citing the need for more legal notice. In Philadelphia, the sheriff suspended foreclosure evictions to allow homeowners and mortgage servicers to work out alternatives.

Zampino said he couldn’t speak for the sheriff in Prince William, but he expected evictions to continue.

“We’re not going to hang up the process in any way,” he said. “We’re just here to do our job. We just keep the peace.”

Two years ago, Zampino did two foreclosure evictions. This year, he’s done “in excess of 100.”

The most difficult cases are ones like Angulo’s, where the former owner remains in the house. “You run into obstacles from time to time,” Zampino explained. “Angry folks … handicapped people with no place to go.”

Asked how Angulo was doing, Zampino paused, then said, “Um … you know.”

Zampino headed back into the house to find Angulo. He told him that the lockout was complete, that all the locks on the doors had been changed and that he had 24 hours to get everything out of the house, or it would be hauled away.

The eviction was officially over, less than a half hour after it began. But Angulo still was allowed to wait a few more hours for his friend to help him move.

Angulo leaned against the wall of the townhouse’s front hallway, still strewn with construction debris, including 2x4s and empty buckets. He constantly worked on the house, he said, trying to fix it up. He spoke quietly in halting English, stopping frequently to keep his emotions in check.

“I tried to talk with the bank, but they wouldn’t help me,” he said. “I got an attorney but he didn’t do anything. I paid him $1,500, but he didn’t do anything.”

He said his troubles began last spring, when he told his renters they had to leave because “they didn’t have their papers.” Both Manassas and Prince William County have law enforcement and zoning efforts that targetillegal immigrants.

At the same time, Angulo’s monthly mortgage payment on an adjustable-rate loan jumped from $1,400 a month to $2,600. He earns about $500 a week as a housepainter.

“I didn’t know what happened,” he said. “I got charged. I can’t pay that.”

Aurora Loan Services, which was foreclosing on Angulo’s house, is a subsidiaryof the failed Lehman Bros. It specializedin Alt-A loans, which required no documentation or downpayment. The firm still services Alt-A loans.

A month ago, knowing that foreclosure and eviction were coming, Angulo sent his wife and two children, a son, 18, and a daughter, 12, back to their native El Salvador.

Does he have someplace to stay tonight?

He shakes his head.

No.

Does he have someone to help him find a place?

No.

“It’s very hard,” Angulo said. He started to say something else, but couldn’t.

Angulo said he looked for an apartment to rent, but $1,500 a month was too much for him. He hasn’t worked in the past few days because of his knee. He owns a truck, a 1986 Nissan, that doesn’t run very well.

He turned down the cash-for-keys offer, he said, because “I wanted to keep the house.” It was a mess when he bought it, and he put a lot of work into it.

At 10:06, as church bells began ringing throughout the neighborhood, Angulo stepped out into the front yard of his former townhouse, listening to Elliott gently repeat the lockout rules and the need for Angulo to get his belongings out of the dwelling. “I’m sorry for your troubles,” Elliott told him.

Angulo said he was still waiting for his friend with the truck.

At 10:14, Angulo sat down, in the cold, on a rusted patio chair next to a small round table in the townhouse’s tiny front yard. He looked down at his hands. He lifted his head, stared into nowhere, rested his hand on his knee, sighed. He put his head down again.

Zampino, who had gone to his car, returned with some brochures for homeless shelters and social service agencies and gave them to Angulo.

“Sir,” he said, “are you going to be OK?”

Angulo said nothing. He took the brochures.

The church bells still were ringing.

Angulo shivered slightly and glanced at the brochures. Zampino and Elliott went to their cars.

As they drove away, Angulo stayed in his chair, holding the brochures and sometimes glancing up at the sky. Just sitting, outside a house that once was his home.

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Hajra Shannona is a highly experienced journalist with over 9 years of expertise in news writing, investigative reporting, and political analysis.

She holds a Bachelor's degree in Journalism from Columbia University and has contributed to reputable publications focusing on global affairs, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

Hajra's authoritative voice and trustworthy reporting reflect her commitment to delivering insightful news content.

Beyond journalism, she enjoys exploring new cultures through travel and pursuing outdoor photography

Latest Articles

Popular Articles