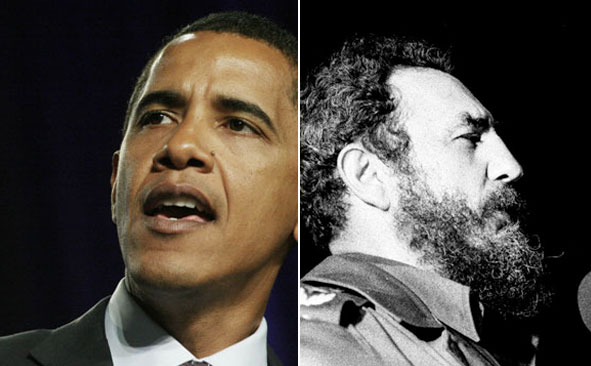

Obama Suggests Cuba Policy Reform

As Cuba celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of its revolution on New Year’s Day, political shifts in the United States present Barack Obama with an opportunity to change long-standing policies.

Jul 31, 2020558.2K Shares7.4M Views

As the world ushers in the new year, Cuba will celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power and sparked an intense political conflict with the United States that has far outlived the Cold War.

President-elect Barack Obama had not yet been born when Castro drove the military dictator Gen. Fulgencio Batista from the island on January 1, 1959. Now, half a century and ten U.S. presidents later, Obama appears likely to lead the first major liberalization of America’s draconian Cuba policy in decades.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

In his U.S. Senate and presidential campaigns, Obama pledged to reverse some of the harsh sanctions on Cuba, imposed over the past fifty years and intensified under President Bush, that have cut off nearly all interaction between the two countries. But while he is likely to open the channels of communication and travel, particularly for Cuban-Americans, it is doubtful that he will make significant reforms to the trade restrictions under the longstanding embargo.

A number of factors free Obama’s hand to make the sorts of changes that have eluded his predecessors. The end of the 49-year reign of Fidel Castro, who in February officially ceded power to his brother Raúl, inspired hope that Cuba would begin to democratize, and very modest reforms have indeed been initiated. But the most significant precondition for improved U.S.-Cuban relations, Latin American policy experts say, has taken place not in Cuba, but here in the United States, with the November presidential election. Where past presidents have been beholden to Cuban-American voters in Florida, Obama proved he could win an election without the previously critical voting bloc.

“U.S. Cuba policy has not been a foreign policy,” explained Shannon O’Neil, the Douglas Dillon Fellow for Latin America Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. “It’s been a domestic policy, based on the Cuban vote in Florida.” In 2000 and 2004, George W. Bush relied on the Cuban vote to carry Florida by narrow margins. Without the Sunshine State, he would not have won either election.

In 2008, however, the equation changed, as Obama won while carrying just 35 percentof the Cuban-American vote in Florida. “The Cubans voted overwhelmingly against Obama,” said Daniel Erikson, director of Caribbean programs at the Inter-American Dialogue and author of The Cuba Wars. “So what the November election shows is that he did not need the Cuban vote to win Florida, and he did not need the Florida vote to win the presidential election.”

Released from the pressures of the Cuban-American constituency, which has generally taken a hard line against Castro’s Cuba and opposed efforts to ease sanctions on the island nation, Obama has some latitude to pursue reform of the country’s Cuba policy. However, it is unclear how this opportunity will translate into reform.

Campaigning in Illinois for the U.S. Senate in 2004, Obama said in a speechthat he wanted “to end the embargo with Cuba” that had “utterly failed in the effort to overthrow Castro.” In the same campaign, he pushedfor the “normalization of relations with Cuba” to “help the oppressed and poverty-stricken Cuban people while setting the stage for a more democratic government once Castro inevitably leaves the scene.” (Instead of an embassy that would allow for full diplomacy, each of the two countries has an “interests section” in the other’s capital with little more than nominal authority.)

But his message during his presidential campaign was substantially different. In August 2007, he told a Miami audiencethat he would not “take off the embargo,” but would preserve it as “an important inducement for change.” However, he did promiseto “grant Cuban Americans unrestricted rights to visit family and send remittances to the island.”

Currently, under the stringent limits imposed by President Bush in 2004, Cuban-Americans can visit Cuba just once every three years, and they are limited to sending no more than $300 annually to their families there.

Obama’s apparent plan to lift these restrictions would have broad support. According to a pollreleased on Dec. 3 by Florida International University, 66 percent of Cuban-Americans in Miami-Dade County — usually among the most vocal opponents of reduced sanctions — want to end the travel limits, and 65 percent hope to see the restriction on remittances lifted.

Still, there will be some resistance if Obama eases the limits on travel and remittances. “There’s a small but influential group of anti-Castro hard-liners in both Cuba and Miami who will fight tooth and nail to prevent these kinds of changes,” said Erikson.

Ray Walser, the Senior Policy Analyst for Latin America at the conservative Heritage Foundation, expressed concern over Obama’s plans. “You’re giving something away to a totalitarian regime without asking for anything in return,” he said. However, he acknowledged that he was probably on the losing end of this battle. “The likelihood is that there will be unilateral concessions from the Obama administration.”

In fact, the changes to the travel restrictions could extend beyond Cuban-Americans. “There is pretty broad support for lifting the travel ban for all Americans,” said Erikson. O’Neil agreed that we might “see the travel restrictions eased, if not lifted, for non-Cubans.”

What is unlikely to change in the near future is the embargo. Instituted by President Kennedy as a security measure — but not before he had an aide buy him 1,200 of his favorite Cuban cigars — the embargo was codified and expanded by the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 and the Helms-Burton Act of 1996. These laws prevent the president from lifting the embargo without congressional approval or from normalizing relations with Cuba while a Castro is still in power.

“Before the passage of Helms-Burton, it was largely a question of presidential discretion,” said Larry Birns, director of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, a liberal think tank. “But Clinton made that concession to the Cuban hardliners.”

Every major presidential candidate since 1992 has supported the trade sanctions against Cuba, according to Erikson. And Obama is no exception. Like other leading politicians, he has described the embargo in terms of leverage, arguing that it should not be lifted until Cuba makes significant democratic reforms.

Walser endorses this notion of reciprocity. “The essence is some willingness on the part of the Cuban regime to change some of its fundamentals,” he said. But because the chances for change are remote, he said that lifting the embargo while Raúl Castro is still in power is going to be difficult.

The idea that the embargo creates leverage has drawn criticism from a number of camps, encompassing both liberals and free trade advocates. “Many people, including Obama, have described the embargo as leverage, but I think that’s a conceptually confused notion,” said Erikson. “What the embargo represents is an absence of leverage.” A free exchange of goods and ideas, embargo critics argue, would much more effectively enable compromise and reform.

While the embargo’s repeal does not appear imminent, O’Neil says it could receive a boost from the agricultural lobby. Farmers would like to gain a new market in Cuba, where they could sell their produce more widely if sanctions were removed.

“Obama doesn’t owe anything to Cuban-Americans,” she said, since they did not contribute to his electoral victory. “On the other hand, Obama doesowe quite a lot to the folks in Iowa for his win.” Obama’s upset victory over Democratic rival Hillary Clinton in the Iowa caucus proved that he could win in rural, majority-white areas and laid the foundation for his eventual nomination.

Kal Wagenheim, editor and publisher of the business website Caribbean Update, agrees that the prospect of new buyers in Cuba is enticing to American growers and manufacturers. “The American business community is dying to get in there,” he said. “There is a strong consensus in the business community — and they’re certainly not communist — to normalize relations with Cuba.”

The embargo has also lost considerable support among the general populace, particularly Cuban-Americans. This year, for the first time, a majority (55 percent) of Miami-Dade Cuban-Americans favor lifting the embargo, according to the Florida International University poll. Just a year ago, that number was 42 percent.

The power to make that change, however, lies with Congress, and a strong and growing contingent of Cuban-American senators and House members continues to oppose any easing of sanctions. Cuban-American lobbying groups in Miami such as the U.S.-Cuba Democracy PAChave raised substantial funds for candidates who share their hard line on Cuba. The result is a Democratic Party that remains split on Cuba, even as a small number of Republicans, including Obama’s new transportation secretary Ray LaHood, have pushed for reform.

So how will the next 50 years of the United States’ relationship with its neighbor across the Florida Straits differ from the half century that is now drawing to a close? According to Erikson, it’s too early to tell.

“The last 50 years of U.S.-Cuban relations have not only been negative for the two countries, but they’ve almost been uniquely bad for bilateral relations between any two counties anywhere in the world,” he said. “So it seems like the future should be much better than the present. But if history has taught us anything about U.S.-Cuban relations, as much as people would like them to get better, they can always get worse.”

Between the economic crisis and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Cuba may not be Obama’s most pressing priority. But as the island crosses this historical milestone, he has an opportunity to apply his mantra of change to an area where it has long been lacking.

Paolo Reyna

Reviewer

Paolo Reyna is a writer and storyteller with a wide range of interests. He graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies.

Paolo enjoys writing about celebrity culture, gaming, visual arts, and events. He has a keen eye for trends in popular culture and an enthusiasm for exploring new ideas. Paolo's writing aims to inform and entertain while providing fresh perspectives on the topics that interest him most.

In his free time, he loves to travel, watch films, read books, and socialize with friends.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles