Don’t Drink the Water: Clean Coal’s Downside

Merle Wertman, now 62, was diagnosed with Polycythemia Vera five years ago. He had no idea what Polycythemia Vera was. That isn’t surprising, considering

Jul 31, 2020423K Shares5.7M Views

Photo Credit: iStockphoto

Merle Wertman, now 62, was diagnosed with Polycythemia Vera five years ago. He had no idea what Polycythemia Vera was. That isn’t surprising, considering less than one in 100,000 Americans a year are diagnosed with the extremely rare form of bone marrow cancer, that causes an abnormal increase in blood cells. What is surprising is that Wertman is one of 131 people near his hometown of Tamaqua, Penn., now battling this rare cancer.

Illustration by:Matt Mahurin

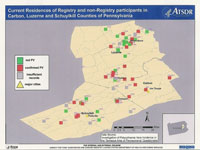

In eastern Pennsylvania’s Carbon, Luzerne, and Schuylkill counties, that surround the Tamaqua borough, the rate of the rare blood cancer is 4.5 times the national rate, according to data from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), a federal public health agency of the Dept. of Health and Human Services. The cancer “cluster” (shown on the mapbelow) follows along Ben Titus Road, next to the Big Gorilla coal combustion waste dump of the Northeastern Power Co. The area is also home to the Superfund sites McAdoo Associates, Air Product & Chemicals Inc., Expert Management Inc. and ICI Americas Inc.

“They have no idea what it comes from. Nobody knows,” said Wertman. “Is it the environment, is it the water? No one knows.” A retired prison guard, Wertman has lived in and around Tamaqua his entire life. He gets angry when he thinks abou

This is also of concern to Dr. Paul Roda, an oncologist and hematologist who is now treating roughly one-third of the PV patients in the area. “In my mind,” he said, “it’s certainly a cluster. You don’t see that many cases in a very small area — particularly a very low population area.”

Roda did point out that another cause could be the materials dumped at the nearby McAdoo superfund site. In the 1970s, toxic chemicals were dumped down a mine ventilation shaft, which led to the Environmental Protection Agency classifying it as a superfund site. “We haven’t done enough studies to know if this is due to coal ash or the material that was dumped down the site.” Roda said.

“„In many areas, where residents get their water from wells, those toxins dissolve directly into the drinking water.

Coal combustion waste, or coal ash, is the solid waste byproduct created when coal is burned. One million railroad cars could befilled with the amount of coal ash produced from coal combustion in the United States each year. When coal combustion waste is disposed in a dump site — usually a mine, landfill, waste pond or out in the open in a sand-and-gravel pit — the toxins from the ash can leach into the groundwater and surface water, often migrating to the drinking water. In many areas, where residents get their water from wells, those toxins dissolve directly into the drinking water.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s own research, coal ash dumping can lead to higher rates of cancer, developmental problems in children and adverse effects in women of child-bearing age. Despite the fact that coal ash contains mercury, lead, arsenic, chromium, cadmium, selenium, beryllium, and other toxic metals, the EPA has yet to categorize coal ash as hazardous waste. In addition, coal ash has been foundto be up to 100 times more radioactive than nuclear waste, due to the concentrations of uranium and thorium that increase 10-fold after coal is burned.

But Northeastern Power Co. Plant Manager Edward Missal says he isn’t aware of any links between coal ash dumping and cancer. “The EPA has taken a look at that and pretty much ruled that out as far as what I’m under the understanding of,” he said.

The solid waste side of coal is being overlooked as environmentalists focus their attention on air pollution and as government agencies and coal companies push “clean” coal technologies. “Cleaner” coal technologies actually produce more toxic coal ash in the resulting solid wase than “dirty” coal technologies, says Jeff Stant of the Clean Air Task Force. These technologies pulverize low-grade fuels in a way that releases fewer pollutants into the air. But those pollutants have to go somewhere, and they end up as ash.

Stant was a contributing author for a recently released report investigating 15 mine disposal sites in Pennsylvania, most of which are dumping sites for ash from Fluidized Bed Combustion (FBC), a “clean” coal technology.

“„The study…found coal ash to be contaminating the groundwater and surface water at levels exceeding federal drinking water standards by 30 to 40 times.

The study, entitled “Impacts on Water Quality from Placement of Coal Combustion Waste in Pennsylvania Coal Mines,” found coal ash to be contaminating the groundwater and surface water at levels exceeding federal drinking water standards by 30 to 40 times.

“Clean” FBC plants produce at least five times more coal ash by volume than standard plants do. These plants inject limestone into the burn chamber to capture more emissions and therefore release fewer emissions-thus the misnomer, “clean.” But, the limestone leaves behind a burned residual, which ends up in the ash. The bigger problem is that “clean” plants burn more waste-coal than actual coal. Waste-coal consists of the impurities removed from coal in addition to some coal itself, and it contains an ash content that’s three times higher than regular coal. Most of the new “clean” coal plants proposed in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and other states will be located next to mines expected to serve as dump sites for coal ash.

The Department of Energy and the coal companies actually promotecoal ash disposal as a “clean coal technology.” The following methods for disposal are being promoted as “beneficial” uses for the environment: mine-filling, agricultural use, use in cement, incorporation into concrete, and use in wallboards. The DOE and the coal industry say these uses are eco-friendly. They say that dumping in mines — or “mine reclamation” as they call it — will clean up the water draining from mines by lowering its acidity. The opposite is actually true, according to the Pennsylvania study, which found that in two-thirds of the sites, more toxic concentrations known to leach from ash were measured in the water after the ash was dumped in the mines. When used for soil amendment in agricultural use, the toxic metals from the ash can be taken up by plants and, again, leech out of the soil into the groundwater. The toxins in the ash can potentially pose problems in cement and concrete, especially in unmonitored facilities.

“I have never seen levels of lead in a mine pool of that magnitude,” says Robert Gadinski, another contributing author of the report. “And that includes lead sites where lead waste is supposed to be dumped. One example — at Marjol Battery in Scranton, Penn., where they dump battery casings and battery waste–even at that site, we never found lead at such high levels.”

Gadinski, a geologist retired from Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection, knows about the dangers of coal ash. That’s why he was none too pleased when he first read in the newspaper about a plan by PPL Utilities to start dumping coal ash in the mine by his house in Mowry, Pennsylvania. “I know that there are mine tunnels from the valley where I live into these mine workings,” Gadinski said. “Any water that comes out of it is going to drain into the valley and go right to the groundwater. Hundreds of wells are at risk here.”

A month later, PPL was ordered by the state Dept. of Environmental Protection to clean up a spill of 100 million gallons of coal ash in the Delaware River due to the toxic and carcinogenic nature of the discharge. “And that’s the same stuff they want to dump here, saying it’s beneficial,” said Gadinski referring to the Dept. of Environmental Protection.

Gadinksi has been fighting the initiative for three years, filing complaints with the state government and appealing the matter to the federal government’s Office of Surface Mining. All to no avail. Though the project was on hold while a new co-generation plant (Schuylkill Energy) took over, the Dept. of Environmental Protection still supports plans to go forward.

The EPA acknowledgesthat coal ash dumping has contaminated the water at levels exceeding federal drinking water standards in Indiana, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin. The only reason more cases have not been documented is that most dump sites lack monitoring systems to detect contamination, says Lisa Evans, an attorney with the Earth Justice environmental group.

“Where we’re finding cases of damage is where there is monitoring data,” said Evans. “But it’s not where the worst disposal practices are. [For example,] data from around 2000 showed that Wisconsin had more sites with contaminated water than other states, but that’s because Wisconsin actually had a better state program, so they were able to detect the contamination.” Evans insists that even though hard data has only been documented in certain states, “this is really an issue everywhere you have coal and don’t have strict regulations for its disposal.”

“„Certainly it suggests that there’s something environmental in that area that would promote an increased instance of that disease.

The EPA released a report publicizingthe health risks of coal ash dumping in 2000. Eight years later, the agency has still taken no action to regulate disposal practices. In August 2007, the agency released a Notice of Data Availability on the Disposal of Coal Combustion Wastes requesting public comments on the data. Now, in the coming weeks, environmental groups will submit their comments and proposals to the EPA, calling for stricter regulations, better monitoring, and investigations to obtain data on coal ash dump sites all over the country.

Whether anything will actually come of this is debatable. Wertman, the former prison guard from Tamaqua, says that in his hometown, politics gets in the way of tackling any of the environmental factors that could have caused his illness.

He talks about a specific case in which the ATSDR admitted that Polycythemia Vera can be tied to environmental factors. Soon after the the public health agency published an abstract (available here) reporting this information in Blood, the science journal for the American Society of Hematology, agency officials started backpedaling. Now, anyone who tries searching for this information on the agency’s website will find a statement contradicting the agency’s own findings by claiming, “No link has been found between environmental factors and PV cases in the Pennsylvania counties Schuylkill, Luzerne and Carbon.”

Dr. Zev Wainberg, an oncologist/hematologist at the Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center and Orthopaedic Hospital, said that the high rates of such a rare disease in this area are surprising. “Certainly it suggests, ” Wainberg said in an interview, “that there’s something environmental in that area that would promote an increased instance of that disease. Because this is an uncommon disease — it’s not a disease that affects that many people, typically, in a small population. But that being said, it’s a lot easier to say that than it is to prove it.”

Paolo Reyna

Reviewer

Paolo Reyna is a writer and storyteller with a wide range of interests. He graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies.

Paolo enjoys writing about celebrity culture, gaming, visual arts, and events. He has a keen eye for trends in popular culture and an enthusiasm for exploring new ideas. Paolo's writing aims to inform and entertain while providing fresh perspectives on the topics that interest him most.

In his free time, he loves to travel, watch films, read books, and socialize with friends.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles