Can U.S. Courts Free Innocent Gitmo Prisoners?

A petition to the Supreme Court filed Monday is being called the first major challenge to the Obama administration’s detention policies.

Jul 31, 20202.2K Shares743.8K Views

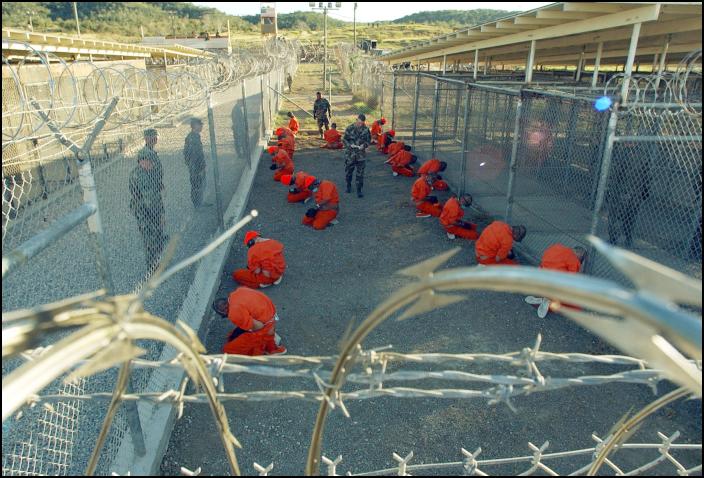

Donald Rumsfeld called the Gitmo detainees "the worst of the worst." (Wikimedia Commons)

In what’s being called the first major challengeof the Obama administration’s detention policy, lawyers on Monday filed a petitionwith the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case of Kiyemba v. Obama, in which a Court of Appeals ruledthat federal courts do not have the power to order innocent Guantanamo detainees released into the United States.

The significance of that ruling goes far beyond the now-notorious caseof the 17 Chinese Muslim Uighursdirectly involved. At its core, the petition asks the Supreme Court more broadly: does a federal court have any power at all over innocent prisoners of the “war on terror”?

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

In the Kiyembacase, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that even though the government had no grounds to continue to hold the Uighurs, imprisoned for more than seven years, the federal courts had no authority to order them released into the United States, either. Their lawyers say that makes their right to habeas corpus — confirmed by the Supreme Court last June in Boumediene v. Bush— meaningless.

“What happens in a habeas case is the judge orders the jailer to release the prisoner,” explained Sabin Willett, the lead lawyer representing the Uighurs. “But there’s no sovereign [government] the court can order except our own. Now the DC circuit is saying the court can’t even do that.”

The result is that not only are these Chinese Muslim dissidents still stuck at Guantanamo Bay, but the Obama administration has used the Kiyemba ruling broadly to argue that all habeas corpus proceedings brought by prisoners approved for release should be halted because the courts have no power to release the men from prison anyway. In other words, when it comes to innocent men imprisoned indefinitely at Guantanamo, the judiciary has no role to play at all.

What’s more, the Obama administration hasbeen using the latest Kiyembaruling to seek a ban on all lawsuitsbrought by former Guantanamo prisoners claiming constitutional violations by U.S. military officials, claiming that the D.C. court ruled that prisoners at Guantanamo Bay have no due process rights.

As I’ve written before, the Uighurs were abducted in Afghanistan (some claim they were sold to U.S. troops for bounty) and sent to Guantanamo Bay, where they’ve been imprisoned for more than seven years even though the Department of Defense and a federal judge have said that they’re not “enemy combatants” and were not fighting against the United States. Some have been cleared for release since 2003. Because they are a persecuted minority in China, however, they cannot return home because they’d face a significant risk of being tortured.

In October, district court Judge Ricardo Urbina ruled, based on “the court’s authority to safeguard an individual’s liberty from unbridled executive fiat” that they must be released.

The Bush administration appealed, arguing that the federal courts have no power to order the release of any foreigners into the United States. That’s a matter only for the executive and his immigration authorities, the government reasoned. Unless the Uighurs apply for asylum and win, they’re doomed to remain at Guantanamo until the administration can find some other place for them to go.

So far, only Albania has been willing to take any; five were sent therein 2006. The U.S. government — which under President Bush deemed all Guantanamo prisoners “the worst of the worst” — hasn’t been able to convince other countries to accept them.

In their petition to the Supreme Court, Willett and his colleagues write that instead of applying the usual standard for a petition for habeas corpus that requires the government to justify the men’s imprisonment, the court wrongly put the burden on the Uighurs to prove their right to release.

Significantly, “no evidence was everoffered to the district court demonstrating dangerousness, involvement in terrorism, criminal activity or any other putative basis for detention,” the lawyers write in their brief to the Supreme Court. “To the contrary, the record contains powerful evidence that Petitioners release would create norisk to the public.”

Given one last opportunity to provide such evidence at the district court hearing, the Justice Department lawyer responded: “I don’t have available to me today any particular specific analysis as to what the threats of — from a particular individual might be if a particular individual were let loose on the street.”

Continuing to hold the innocent men indefinitely, then, violated a “fundamental right of liberty” that the courts must protect against “unbridled executive fiat,” the court ruled. “[T]he carte blanche authority the political branches purportedly wield over [the Uighurs] is not in keeping with our system of governance,” Judge Urbina wrote, and ordered that the Uighurs be released.

A three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals, however, disagreed. In a 2-1 decision, the court decided that the question ultimately fell under the immigration laws, even though the Uighurs had never applied for refugee status or to immigrate to the United States. Citing a 1889 case that upheld the executive’s right to exclude all Chinese immigrants, the court held that it is “the exclusive power of the political branches to decide which aliens may, and which aliens may not, enter the United States, and on what terms.”

“Not every violation of a right yields a remedy, even when the right is constitutional,” the circuit court majority wrote, and ultimately, no alien has a right to admission to the United States. The court could provide nothing more for the prisoners than an assurance that the executive branch would keep trying to resettle them in another country.

Lawyers for the prisoners argue that the ruling essentially eviscerates the Supreme Court’s ruling in Boumediene v. Bush, which confirmed that prisoners at Guantanamo Bay have the right to habeas corpus review.

“The Kiyembamajority’s taxidermy would hang Boumedieneas a trophy in the law library, impressive but lifeless,” write the lawyers in their petition.

Put another way, “if the court doesn’t take this case and reverse this case, then Boumediene was a whole lot of nothin’,” said Willett yesterday. “Because right now they’re in the strange situation that they’re all sitting in Guantanamo.”

In effect, the ruling applies not only to the 17 Uighurs but to every detainee that has been, or will be, cleared for release, he said. So far, more than 60 prisoners have been cleared but remain at the prison. “You can’t order a foreign government to accept anyone, even its own citizen,” said Willett. “So the court can’t make those prison gates open in any case if they don’t take and reverse this case.”

Some legal experts are more sympathetic to the government’s view that the prisoners’ release should be handled by the executive.

Glenn Sulmasy, for example, an expert on national security law at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, said the D.C. Circuit was right that the district court’s ruling interfered with immigration laws. The Court of Appeals was “trying not to trump existing immigration law that might have long term consequences for those who did not live in the U.S.,” he said.

Indeed, a part of the federal immigration law — the REAL ID Act of 2005— would exclude any immigrant who has received terrorist training or belonged to an organization that promotes terrorism. Although the Uighurs were not planning to fight the United States, at least some are alleged to have been in weapons training in Afghanistan.

“The Uighurs are excludable on both grounds, even if one accepts, for argument’s sake, that they were trained for the purpose of conducting operations against China,” wrote Andrew McCarthy, senior fellow of the National Review Institute in a recent debatein The New York Times about the Uighurs’ situation.

To the lawyers representing the prisoners, however, that’s irrelevant, because the Uighurs were not trying to immigrate to the United States. The case therefore shouldn’t be decided under immigration law, but under the law governing the writ of habeas corpus. “The core proposition of the Great Writ is that the jailer has the burden to demonstrate positive law authorizing imprisonment,” they write in their brief to the Supreme Court. “Where he cannot do so, the court must order release, and the jailer must comply.”

More broadly, the Uighurs’ case highlights the complex problem facing the Obama administration due to Bush administration’s waging of the so-called “war on terror.”

“The authorization for the use of military forcewas so broad, using terms like the ‘war on terror,’ that it provided an opportunity for folks we were not engaged in armed conflict with to get swept up in this,” said Sulmasy. “Words matter. ‘War on terror’ means we’re at war against all terrorists. Even folks like the IRA, The Red Brigades, Shining Path, FARC. But we’re clearly not at war with those people,” he said. “What we’re really at war with is al Qaeda.” Because of the language used, “we’re holding folks alleged to be terrorists, but not enemies of the United States.”

How the Supreme Court will view the case — and how the Obama administration, which has so far supported its predecessor’s broad claimsof executive power, will argue it — is hard to predict.

“There are no exceptions to the habeas provision as written in the constitution that would permit this kind of detention,” said Diane Marie Amann, a law professor at University of California, Davis who specializes in international and cross-border crime. Then again, she added: “the constitution wasn’t written after September 11.”

Camilo Wood

Reviewer

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles