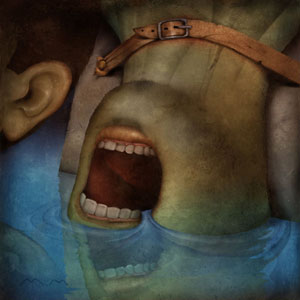

A Torture Mystery

In one technique, the detainee’s weight is borne by his legs and feet during sleep deprivation, ensuring that he had to keep awake, for if he los his balance from exhaustion he would feel the restraining tension of the shackles.

Jul 31, 202030.8K Shares3.8M Views

The floor of the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters (Wikimedia)

Hidden in plain sight in the Office of Legal Counsel memos on the CIA interrogation is a mystery: How did the “enhanced interrogation” technique of sleep deprivation come to depend on stress positions?

Somehow, between 2002 and 2005, CIA interrogators began using what the International Committee of the Red Cross called “prolonged stress standing” as a means to keep detainees from falling asleep so as to make them docile and cooperative when questioned. What isn’t clear is how that non-intuitive sense of “sleep deprivation,” which was not mentioned in the initial legal authorization for the technique, came into official CIA usage. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence will examine that development in its ongoing review of CIA interrogations and detentions, according to knowledgeable sources.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

In an August 1, 2002 memorandum outlining interrogation methods that the CIA could lawfully employ on captured al-Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah, then-OLC chief Jay Bybee authorized the technique of sleep deprivation, writing that the CIA’s goal was “to reduce the individual’s ability to think on his feet and, through the discomfort associated with lack of sleep, to motivate him to cooperate” with his interrogators. There is no discussion in the memorandum, declassified by the Obama administration on April 17, about how the CIA would keep Abu Zubaydah awake. Yet Bybee wrote, “it is clear that depriving someone of sleep does not involve severe physical pain within the meaning of the [federal anti-torture] statute. … Based on the facts you have provided us, we are not aware of any evidence that sleep deprivation results in severe pain or suffering.”

But by the time the OLC reevaluated the CIA’s interrogation program in 2005, it revealed that the technique was overwhelmingly physical. “The primary method of sleep deprivation involves the use of shackling to keep the detainee awake,” wrote Bybee’s eventual replacement, Steven Bradbury, on March 10, 2005. “In this method, the detainee is standing and is handcuffed, and the handcuffs are attached by a length of chain to the ceiling.” The detainee’s feet are shackled to a bolt in the floor, giving him a “two-to-three-foot diameter of movement.” His hands “may be raised above the level of his head, but only for a period of up to two hours.” His weight is “borne by his legs and feet during sleep deprivation,” ensuring that he had to keep awake, for if he “los[t] his balance” from exhaustion he would feel “the restraining tension of the shackles.”

Both memos gave legal approval to the use of stress positions like shackling. And both memos contemplated and blessed the use of techniques in combination with each other, finding that no conceivable permutation of combined techniques would constitute “severe pain or suffering” or “severe mental pain or suffering.” But until the release of the 2005 memo, there had been no official acknowledgment that sleep deprivation as practiced by the CIA depended on physically restraining a detainee.

Experts say individual methods of torture are commonly combined, and can have more than one physiological or psychological effect. “Each term, like ‘stress positions,’ covers a wide variety of techniques, but they’re used together,” said Scott Allen, a Rhode Island-based doctor and medical adviser to Physicians for Human Rights. “With the use of a stress position, it’s virtually impossible for someone to sleep.”

The stress positioning was not the only technique involved in the sleep deprivations. According to Bybee in the 2005 memorandum, detainees undergoing sleep deprivation could also be “subject to nudity as a separate interrogation technique.” Whether nude or not, a detainee experiencing sleep deprivation wore “an adult diaper,” which the CIA assured Bradbury would be “checked regularly and changed as necessary.” Since the use of the diaper “is not used for the purpose of humiliating the detainee,” the CIA did not consider it to be “an interrogation technique.” According to the memo, the “maximum allowable duration for sleep deprivation” is “180 hours,” or seven and a half days, “after which the detainee must be permitted to sleep without interruption for at least eight hours.”

A footnote to the memo indicated that there was an associated technique of keeping a detainee awake through “horizontal sleep deprivation.” In that technique, “the detainee’s hands are manacled together and the arms placed in an outstretched position — either extended beyond the head or extended to either side of the body — and anchored to a far point on the floor in such a manner that the arms cannot be bent or used for either balance or comfort.” Interrogators would place similar restraints on the detainee’s legs. “The position is sufficiently uncomfortable to detainees to deprive them of unbroken sleep, while allowing their lower limbs to recover from the effects of standing sleep deprivation,” Bradbury wrote.

It is unclear how the CIA came to believe that shackling and stretching a detainee was an allowable form of inducing sleep deprivation, but senior CIA officials approved of the determination. According to the memorandum, on January 28, 2003, then-CIA Director George Tenet issued two “guidelines,” one on interrogations and one on detentions policy, which are still classified. Hints appear in the May 10, 2005 memorandum: use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” required prior written approval “from the Director [of the] Counterterrorist Center, with the concurrence of the Chief, CTC Legal Group,” and a “contemporaneous record shall be created setting forth the nature and duration of each such technique employed.”

Attempts to reach Tenet for comment were unsuccessful, as were attempts to solicit responses from key Tenet-era CIA deputies. The CIA declined to comment for this article.

In a confidential February 17, 2007 report by the International Committee of the Red Cross — recently obtained and published by the New York Review of Books’ Mark Danner — several detainees formerly in CIA custody who had been subjected to stress-position-based sleep deprivation described the practice. “I was kept sitting on a chair, shackled by hands and feet for two to three weeks,” said Abu Zubaydah. “If I started to fall asleep a guard would come and spray water in my face.” The cell in which he was kept was “kept very cold” through air conditioning, according to the Red Cross report, and “very loud ‘shouting’ music was constantly playing on an approximately fifteen minute repeat loop twenty-four hours a day.” Other detainees said that feces would run down their legs “when they defecated while held in the prolonged stress standing position.”

Several other detainees — 9/11 architect Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and his aide Ramzi bin al-Shibh; as well as Majid Khan, Khalid bin Attash, Abdulrahim Hussein Abdul Nashiri, Mohammed Nazir bin Lep and Encep Nuraman — described being “shackled to a bar or hook in the ceiling above the head for periods ranging from two or three days continuously, and for up to three months intermittently,” according to the Red Cross report. If a detainee managed to fall asleep despite the shackling, “the whole weight of their bodies was effectively suspended from the shackled wrists, transmitting the strain through the arms to the shoulders.”

Allen of Physicians for Human Rights said a number of long-term ailments could emerge from extended use of the stress position. “There’s traumatic arthritis, tendon and muscle problems further down the road,” he said, including long-term nerve damage, swelling of the feet and ulceration, among other ailments.

While much remains unclear about the CIA’s merging of stress positions and sleep deprivations, Allen found one aspect of the story to be less than mysterious. “Common sense will tell you that the longer someone is held in these positions, the greater risk of injury,” he said.

Camilo Wood

Reviewer

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles