Obama Administration Abandons Cramdown

Once a central element to the administration’s plan to help underwater homeowners, cramdown is no longer part of the debate.

Jul 31, 20207.3K Shares366.2K Views

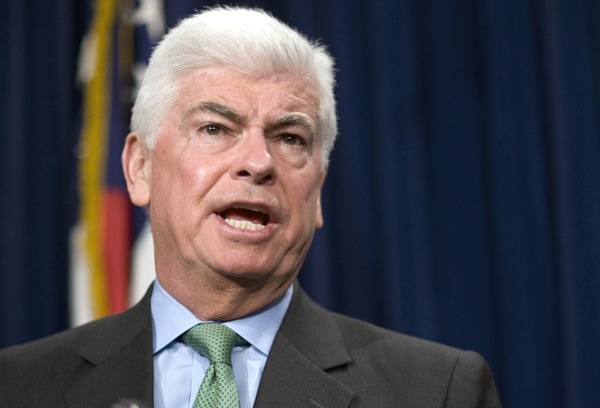

Sen. Chris Dodd (R-Conn.) (WDCpix)

As housing foreclosures top the 1.5-million mark this year, the Obama administration has openly abandoned cramdown as a strategy for tackling the crisis.

That approach — which would empower homeowners to avoid foreclosure through bankruptcy — was once a central element of the administration’s plans to stabilize the volatile housing market. Some financial analysts say the strategy would prevent 20 percent of all foreclosures. But, appearing before a Senate panel Thursday, two White House officials said that current policies are enough to address the problem.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

“We have enough tools,” Herbert Allison, the Treasury Department’s assistant secretary for financial stability, told members of the Senate Banking Committee. “The challenge is to roll them out.”

The tools Allison invoked are several federal programs that offer financial incentives to mortgage lenders and servicers — the companies that buy the rights to manage loans — to modify the terms of mortgages in efforts to help homeowners escape foreclosure. Yet those programs rely largely on the cooperation of the finance industry to alter the loans voluntarily. Many lawmakers and consumer advocates argue that the companies aren’t doing enough to comply with the modification programs. The carrots without a strong stick, they say, just aren’t working.

“Why am I still reading stories about homeowners, community advocates, even my own staff acting on behalf of constituents, shuffled from voicemail to voicemail as they attempt to help people stay in their homes?” asked Sen. Christopher Dodd (D-Conn.), chairman of the Banking Committee.

It wasn’t supposed to work out this way. When the Obama administration unveiled its Making Home Affordable program in February, it estimated that the initiative would entice servicers to modify loans helping between 3 million and 4 million families keep their homes. To date, 325,000 modifications have been offered under the program, according to Allison. Of those, 160,000 are currently in a three-month “trial-modification” period. If borrowers prove they can meet the terms of the modifications over that span, then the changes become permanent.

Under a separate program to help underwater borrowers refinance their loans, just 43,000 homeowners have been helped, Allison said.

Those numbers pale in comparison, however, to the wave of foreclosures that continues to wash across the country. In the first half of this year, more than 1.5 million homes have entered into the foreclosure process — up 15 percent from the same period last year, according to the latest figures from RealtyTrac, an online foreclosure database. More than 336,000 filings occurred in June alone, RealtyTrac found — a jump of about 15,000 from the month before.

And the numbers are expected to increase alongside rising unemployment — a trend that’s expected to continue through the end of the year.

For supporters of cramdown, the numbers offer compelling evidence that the voluntary programs aren’t doing enough to stem the foreclosure crisis. Providing homeowners with the option of bankruptcy, they say, would offer the threat to accompany the administration’s incentives, empowering judges to reduce, or “cramdown” the rates and principals of primary loans. Under current law, that option is available to owners of vacation homes, yachts and almost any other material possession, but family homes are exempt.

Mary Coffin, executive vice president of Wells Fargo’s mortgage servicing division, said the bank has already helped nearly 1 million homeowners this year with refinancings and loan modifications. In June, Coffin noted, 83 percent of the modifications resulted in lower payments for homeowners.

The cramdown issue is hardly new to Capitol Hill. In March, the House passed a cramdown bill that was widely expected to sneak through the Senate on its way to becoming law. It didn’t happen. Instead, the bill fell 15 votes short of upper chamber approval — a failed effort occurring while the White House watched in silencefrom the sidelines.

Last week, House Democrats on the Financial Services Committee staged a hearingto rue the bill’s failure in the Senate. But upper-chamber lawmakers appear resigned to the fact that it simply doesn’t have the votes to pass.

“Obviously, it would have been better to have the stick of bankruptcy involved,” Sen. Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) said of Washington’s anti-foreclosure efforts. “But it’s not in the cards.”

Indeed, during Thursday’s three-hour Banking hearing, Schumer’s words marked the only explicit mention of cramdown at all. Afterward, Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.), who chairs the Banking Committee’s housing subpanel, said bankruptcy reform was among “the quickest and least costly” ways to stem foreclosures, but supporters lacked “the political capital to make it happen.”

Allison declined to take questions following the hearing, and the White House did not respond to additional calls for comment.

The lack of interest on Capitol Hill could spell bad news for millions of homeowners around the country. The White House hopes to have their programs running at full throttle by the fall, Allison said. But he warned that they are multi-year efforts, and the administration anticipates “millions” more foreclosures, even if the programs underway meet all of their goals.

A Credit Suisse report unveiled in December found that cramdown would prevent 20 percent of foreclosures — a number that remains relevant, one author of that report said Thursday.

Hampering efforts to tackle the crisis, there remains some disagreement over why lenders and servicers have been reluctant to repackage loans so that they become affordable. Paul Willen, senior economist at Boston’s Federal Reserve, had perhaps the simplest theory.

“The most plausible explanation for why lenders don’t renegotiate,” Willen said, “is that it simply isn’t profitable.”

Willen suggested a foreclosure-prevention program in which the borrowers receive direct assistance — either through grants or affordable loans — rather than offering the incentives to the servicers to help homeowners only if they choose to. “If such a program existed, Willen said, “we would have solved this problem by now.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles