Obama Defies Federal Courts in Holding Yemeni Detainees

On Monday a federal court judge ordered the Department of Defense to release a 47-year-old father of two with a heart condition who it has imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay for the past seven years without justification.

Jul 31, 2020178K Shares6.5M Views

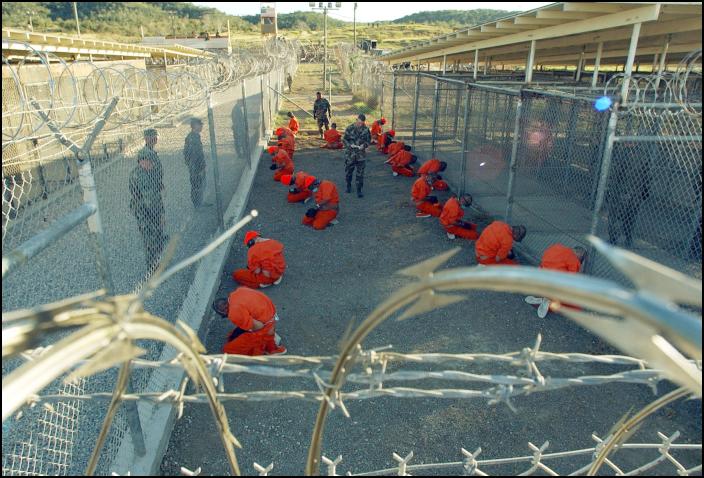

Donald Rumsfeld called the Gitmo detainees "the worst of the worst." (Wikimedia Commons)

On Monday a federal court judge ordered the Department of Defense to release a 47-year-old father of two with a heart condition who it has imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay for the past seven years without justification. But like the other Yemeni men cleared for release but still held at the detention facility, it’s not clear when or even if Mohammed al-Adahi will get to go free.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Obama administration officials on Wednesday boastedthat they’d secured agreements from six European countries to accept Guantanamo detainees, although the United States itself has still refused to free any Guantanamo prisoners on U.S. soil. But since President Obama’s inauguration in January, the administration has not released a single prisoner to Yemen, although that country is willing to have them back and many would be happy to go there. (Some prisoners from other countries, such as the Uighurs from China, cannot be returned to their home countries for fear of persecution.) The administration has not stated its reasons, but said only that the State Department is negotiating with the Yemeni government over the prisoners’ return. At least three Yemeni prisoners since April have won their petitions for habeas corpus in federal court — meaning a judge has ordered that the government must let them go. (The government has cleared for release an unknown number of others.) So far, though, the Obama administration has not complied with those court rulings.

The United States has long been reluctant to return Guantanamo detainees to Yemen, where al-Qaeda is believed to be active. As a result, of about 550 prisoners released from Guantanamo by Bush officials, only 14 were from Yemen. But that trickle has slowed to a complete halt under the Obama administration, despite court rulings that the government hasn’t shown the men have done anything wrong or present any security risk.

Nearly 100 of the remaining 223 detainees at Guantanamo Bay are from Yemen. A government official on Wednesday said that negotiations are ongoing. Now that two U.S. federal courts have ordered at least three Yemeni prisoners freed, however, it’s not clear under what power the United States can continue to hold them.

“We appreciate that the United States has security concerns about Yemen, but continuing to hold these men without charge is morally wrong, is in violation of court orders, and it’s handing al-Qaeda a recruiting tool,” said Letta Taylor, a researcher for Human Rights Watch who wrote a report on the Yemeni detainees’situation in March. “It creates its own sets of risks.”

The standoff between the court and the president in the Yemeni prisoner cases is another example of the executive branch ignoring the orders of the federal judiciary. In previous court cases, the government has refused to turn over evidencethat it deemed a “state secret,” for example, even after a federal judge ordered the evidence be disclosed.

“The way our system is supposed to work is that if a federal district court orders that a branch of the government do something, they’re supposed to do it,” said John Chandler, a lawyer in Atlanta who represents al-Adahi in his court case and won his order of release on Monday. “I have every hope that they will. But they haven’t done anything yet. And he’s not the first one to be ordered released.”

In April, Judge Ellen Huvelle granted the habeas corpus petition of Yasin Muhammed Basardah, a Yemeni who was known to have provided information— often found to be unreliable — against other Guantanamo detainees. As a result, he faces security risks wherever he’s released.

And in May, Judge Gladys Kessler ordered the release of Alla Ali Bin Ali Ahmed, a Yemeni man arrested seven years ago as a teenager. The Pentagon claimed he was a terrorist based largely on statements from other Guantanamo prisoners whose testimony the judge deemed unreliable, as well as bits and pieces of other circumstantial evidence that Judge Kessler found were too “weak and attenuated” to support his continued detention.

Despite the federal court orders to release them, both men are still at Guantanamo Bay. And many more Yemenis have been cleared for release by the U.S. government, although in a strange twist, the government refuses to say how many and their lawyers are forbidden from divulging this information to the media. Among them is a 38-year-old orthopedic surgeon captured in Afghanistan in January 2002, who the Justice Department announced in March that it had cleared for release. Two more Yemeni prisonersat Guantanamo apparently committed suicide, according to the government.

“The government is designating the very fact of approval for transfer ‘protected’ information, meaning it can’t be disclosed to anyone who has not committed to obeying the protective order – which in turn prohibits the disclosure of ‘protected’ information,” explained David Remes, Executive Director of the nonprofit group Appeal for Justice, and a lawyer representing more than a dozen detainees from Yemen. “All of us are fighting that ["protected"] designation in our cases.”

Al-Adahi, who won his order of release on Monday, was captured by Pakistani troops while fleeing Afghanistan after the U.S. invasion. Because he was on a bus that also carried some wounded Taliban soldiers, the Defense Department claimed he was working for the Taliban and sent him to Camp X-Ray at Guantanamo Bay in January 2002.

An oil worker who lived in Yemen, Al-Adahi was originally suspected of acting as Osama bin Laden’s bodyguard, but he has consistently maintained his innocence. In June, he testified to a closed federal courtroom via video camera from Guantanamo, where he was chained to the prison floor and sweating in the Caribbean heat. Al-Adahi talked about his high blood pressure, and Guantanamo officials have confirmed he has heart problems.

According to declassified portions of the transcript, Al-Adahi testified that he was introduced to Osama bin Laden during the summer before the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks while he was in Afghanistan, where he was bringing his sister, who the family had arranged to marry a Yemeni man in Kandahar. Bin Laden, then considered the de facto “governor” of Kandahar, was at the wedding celebration. Al-Adahi has consistently maintained that he never worked for bin Laden, and Judge Kessler apparently believed there was insufficient evidence to support the government’s claims. Her written opinion in the case has not yet been declassified, however, so the basis for her findings remain unclear.

“I did not fight the American alliance,” Al-Adahi testified. “I did not deal with Taliban or al-Qaeda. I am a working man in my country. I have never committed a crime.”

The Department of Justice referred questions about the repatriation of Yemeni detainees to the State Department. A State Department spokesman said he cannot comment on the situation of Yemenis who have brought their cases to federal court.

Of the 35 habeas corpus cases heard so far, federal courts have granted the petitions and ordered the release of 29 Guantanamo Bay detainees, finding the government has not produced enough evidence to keep holding them. In addition to the three Yemeni prisoners whose petitions have been granted, the petitions of three others from Yemen have been denied.

Update: Judge Kessler released this unclassified, redacted version of her opinionin the al-Adahi case late on Friday. In the opinion, she says there is no reliable evidence that al-Adahi was ever a member of or fought for al-Qaida or the Taliban, or provided either group any affirmative support.

Dexter Cooke

Reviewer

Dexter Cooke is an economist, marketing strategist, and orthopedic surgeon with over 20 years of experience crafting compelling narratives that resonate worldwide.

He holds a Journalism degree from Columbia University, an Economics background from Yale University, and a medical degree with a postdoctoral fellowship in orthopedic medicine from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Dexter’s insights into media, economics, and marketing shine through his prolific contributions to respected publications and advisory roles for influential organizations.

As an orthopedic surgeon specializing in minimally invasive knee replacement surgery and laparoscopic procedures, Dexter prioritizes patient care above all.

Outside his professional pursuits, Dexter enjoys collecting vintage watches, studying ancient civilizations, learning about astronomy, and participating in charity runs.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles