Democrats Split on Patriot Act

Republicans and Democrats have been sniping about the USA Patriot Act ever since Congress passed the law in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks to try to forestall another such disaster.

Jul 31, 202021.2K Shares3.5M Views

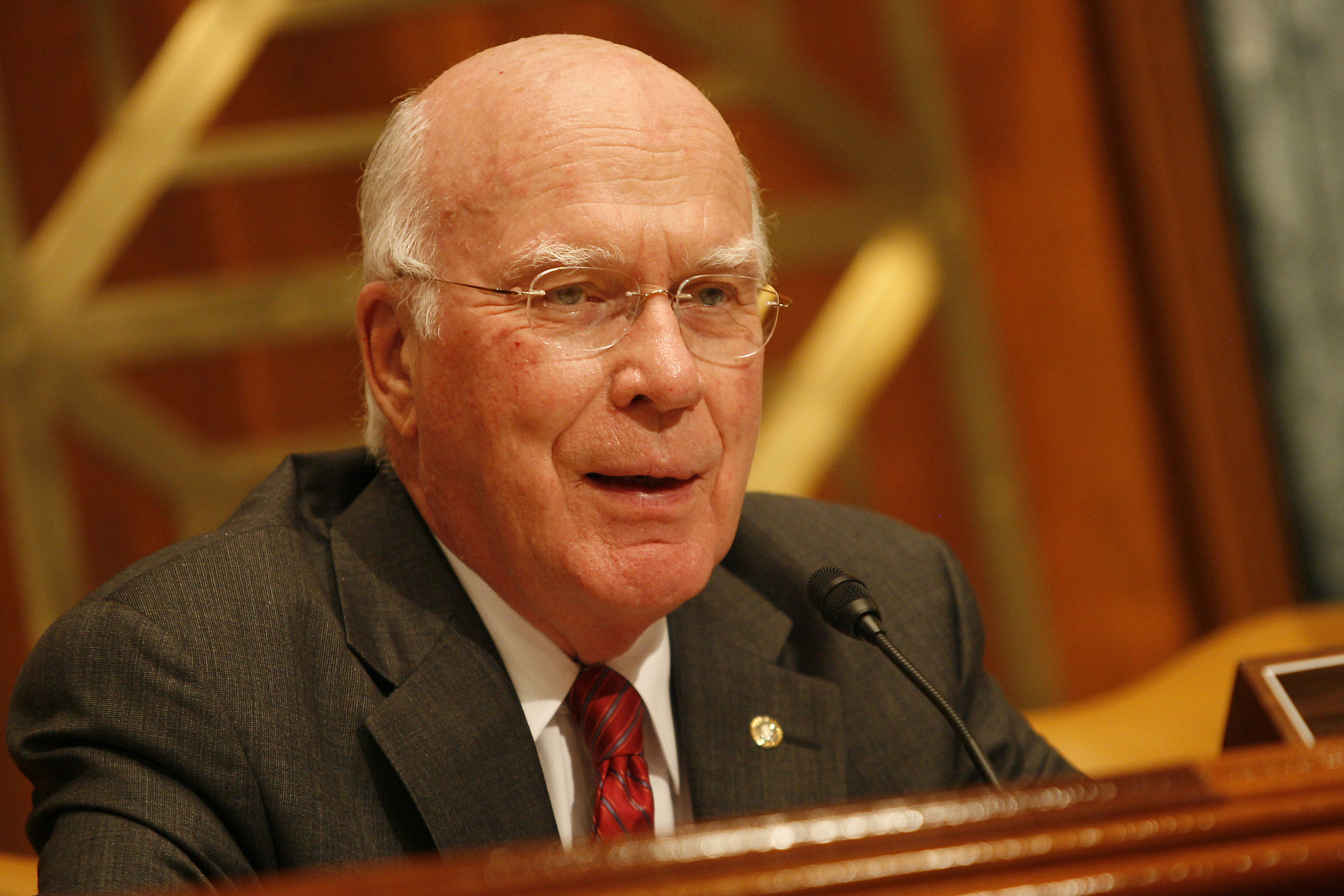

Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) (Zuma Press)

Republicans and Democrats have been sniping about the USA Patriot Act ever since Congress passed the law in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks to try to forestall another such disaster. But now, it’s the Democrats who are sniping among themselves about it. While some lawmakers, like Sens. Russ Feingold and Dick Durbin, have insisted that Congress must amend the law to rein in the FBI’s powers to snoop into innocent private activities, other Democratic lawmakers, such as Sens. Dianne Feinstein and Patrick Leahy, have resisted significant reforms.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Three provisions of the law will expire by the end of this year if they’re not renewed, and have been the subject of recent hearings. Those are: the “roving wiretap” provision, which allows the government to tap phones and other electronic devices used by any person suspected of involvement in terrorism; section 215 of the Patriot Act, which allows the government to obtain a broad range of business records and other tangible things, including library records, subscription information and credit card statements, so long as the FBI shows these are “relevant” to some terrorist investigation; and the so-called “lone wolf” provision, which allows the government to wiretap any suspect believed to be involved in terrorism, even if that person has no connection to any known terrorist organization.

The other controversial provisions include the FBI’s authority to issue National Security Letters, or NSLs, which seek a broad range of information from businesses about their customers but do not require a warrant or any other court order; and the “sneak and peak law”, which allows the FBI to search a suspect’s home without informing the target that they’ve been searched.

Civil liberties advocates insist these provisions are all too broad as currently written, and allow the FBI to abuse its authority to conduct wide-scale “data mining” of the general population, searching innocent people’s records and personal information while the government tries to root out wrongdoing. Because in many cases it’s not clear how the government is using its broad authority and who gets access to the information, privacy advocates worry that the government could retain such information and use it in ways unconnected to terrorism investigations.

A 2007 report from the FBI Inspector Generalconcluded that the FBI had issued almost 150,000 NSL requests between 2003 and 2005, often collecting information about people not even suspected of having done anything illegal. The Inspector General also found that the FBI’s record-keeping was so poor that it often didn’t know how many letters it has issued, and requested information it wasn’t entitled to receive.

Advocates worry that many sections of the Patriot Act allow similar abuses. “The concern is that the changes the Patriot Act made were such that so long as the FBI agent certifies that the information they’re seeking is relevant to a terror investigation, they can get it,” explained Farhana Khera, Executive Director of Muslim Advocates, which recently sued the governmentfor more information about FBI surveillance practices. “We argue that’s way too broad. It should be tied to a suspected terrorist or terrorist activity.” The FBI’s current authority “has unleashed concerns about the FBI getting access to data on literally millions and millions of Americans,” she said.

Advocates for Muslim-Americans also worry that the laws are being used to target and harass law-abiding American muslims, landing them on no-fly lists, preventing them from getting hired for federal jobs, or deterring them from contributing to legal charitable organizations that assist needy Muslims in other countries.

To address these problems, in mid-September, Feingold and Durbin, both of whom have long expressed concerns about the Patriot Act, introduced the JUSTICE Act (Judiciously Using Surveillance Tools In Counterterrorism Efforts), which would renew section 215 and the roving wiretap provisions, but would require the government to provide more justification for using them, and to specify more clearly the targets of their investigation.

The bill would also rein in the FBI’s authority to issue National Security Letters by requiring the government to specify what it’s looking for and how the information is relevant to an ongoing national security investigation. Meanwhile, it would repeal the part of the FISA Amendments Act that immunized telecommunications companies such as AT&T that assisted the government in its warrantless wiretapping program.

But a week later, to the dismay of many civil libertarians, Sen. Leahy introduced the USA Patriot and Sunset Extension Act. Cosponsored by Sens. Benjamin Cardin (D-Md.) and Ted Kaufman (D-Del.), it would extend the expiring provisions with only minor modifications, and would leave the “lone wolf” and “roving wiretap” provisions intact. It also would not include any reforms to the FISA Amendments Act.

By the time of the Senate markup session last week, Sen. Leahy, the Judiciary Committee Chairman, had produced a substitute version of his bill, co-sponsored by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), who chairs the Intelligence subcommittee. This bill became the basis for the markup, effectively destroying the chances for adoption of the JUSTICE bill, although pieces of it could still be introduced as amendments.

Civil liberties advocates quickly expressed their disappointment. The American Civil Liberties Union called it“a watered-down version” of the original Leahy bill. Kevin Bankston of Electronic Frontier Foundation similarly described itas having “even fewer PATRIOT reforms than the original Leahy bill.” Although Feingold and Durbin offered amendments, the only one that succeeded was one amending the “sneak and peak” provision. The amendment would require the government to notify the subject of a search within seven days, instead of 30, as the law stands now. An amendment offered by Senator Durbinto narrow the broad Section 215 powers, which now allows the government to gain access to “any tangible thing,” failed.

Even Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.), who at the recent Senate Judiciary Committee hearing took the time to read the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitutionto Justice Department official David Kris, voted to support the Leahy-Feinstein substitute bill, and against the Durbin and Feingold amendments.

Feingold has repeatedly expressed concern that the government is not providing enough information for the public to know how the Patriot Act is being used.

“I remain concerned that critical information about the implementation of the Patriot Act remains classified,” said Feingold at a recent hearing, noting that he believes that much of that classified information “would have a significant impact on the debate.” Although the Justice Department recently acknowledged that the “lone wolf” authority has never been used, said Feingold, “there also is information about the use of Section 215 orders that I believe Congress and the American people deserve to know.”

Some representatives in the House, where they’re also debating changes to the Patriot Act and will eventually put forward their own bill, feel the same way. Earlier this week, Reps. John Conyers (D-Mich.), Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), and Bobby Scott (D-Va.) wrote a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder asking for more information about how Section 215 orders have been used to help inform the House debate. (Eventually, the House and Senate bills to amend the Patriot Act will have to be reconciled before they go to the President for his signature.)

Although Feinstein has cited classified informationas her reason for supporting the re-authorization of section 215 as is, Feingold disagrees. The Feingold amendment would have limited what kinds of records could be obtained under section 215, and required that the government show that those records are related either to terrorist activities, or to people in contact with a terrorist.

Interestingly, notes Michelle Richardson, legislative consultant to the ACLU, during the Patriot Act reauthorization process in 2005, “Democrats and Republicans supported amendments to section 215 to limit it to terrorist activities,” she said. “But now they don’t.”

The problem with reauthorizing many of these provisions, says Richardson, is that “we don’t know what information they’re getting, how much, and who has access,” she said. “But we believe that anytime you get the information, it’s a violation. These are principles over 200 years old in this country, that government should not be getting this information about you unless they have reason to believe you’ve done something wrong.”

That principle is increasingly being discarded. Attorney General Guidelines issued at the end of the Bush administration, for example, eliminated the requirement that the FBI must have reason to believe the target of an investigation has committed a crime before initiating that investigation.

“Who knows if the information comes back to haunt you,” said Richardson. “If you apply for federal student aid, for a federal job, or end up on a no-fly list. We don’t know who has access to the information, and where it’s supposed to go. That’s not how things are supposed to work in this country.”

On Thursday, the markup session will continue in the Senate Judiciary Committee, as specifics on the bill get hammered out. Much of the critical information necessary to determine how it’s working, though, will remain secret.

Camilo Wood

Reviewer

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles