9/11 Masterminds Could Face Trial in Federal Court

The possibility prompts fervent opposition from Republicans, who say the 9/11 terrorists should never be allowed anywhere on U.S. soil, let alone in a civilian U.S. court.

Jul 31, 2020263.1K Shares6.2M Views

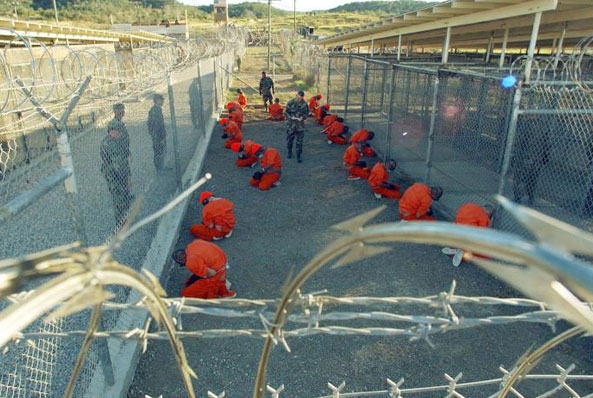

Salim Hamdan, Osama bin Laden's alleged driver, was held in Cuba at Guantanamo Bay prison camp like these detainees. (Department of Defense photo by Petty Officer 1st class Shane T. McCoy, U.S. Navy)

As the Obama administration nears its deadline for deciding where to try the men suspected of masterminding the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorists attacks, there are strong indications that those trials could take place in federal courts in the United States. That’s prompting fervent opposition from Republicans, who say the 9/11 terrorists should never be allowed anywhere on U.S. soil, let alone in a civilian U.S. court.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Military Commissions lead prosecutor Capt. John F. Murphy told reportersin September that four different U.S. attorneys offices in New York, Washington and Virginia were vying for the opportunity to try the five now-infamous defendants, which include Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the self-described mastermind of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Walid Muhammad Salih Mubarek Bin ‘Attash; Ramzi Binalshibh; Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, and Mustafa Ahmed Adam al Hawsawi are the other four. According to Murphy, the Eastern and Southern Districts of New York, based in Brooklyn and Manhattan, respectively; the Eastern District of Virginia, based in Alexandria; and the District of Columbia had all submitted requests to hold the high-profile trials in their courthouses, and to detain the suspects in their jails during trial. The military commissions are also seeking to try the defendants.

Meanwhile, White House lawyers, a task force advising the president, and President Obama have all said that their preference is to try terror suspects in federal courts whenever possible, although they have not ruled out the possibility of using military commissions to try some of them. It remains unclear which ones.

The administration has promised to make its final decision on where to try the 9/11 suspects by Nov. 16. Fearing that the administration is inching toward bringing them to New York City or the Washington, D.C., area, opponents of trying high-level terrorists in U.S. federal courts are stepping up their efforts to keep the five men out of the United States for any purpose. On Oct. 9, Sen. Lindsey Graham said he’d attached an amendment to an appropriations bill that would prohibit the Obama administration from spending money on prosecuting and trying these five alleged terrorists in U.S. civilian federal courts.”Khalid Sheik Mohammed needs to be tried in a military tribunal,”Graham told McClatchy Newspapers. “He’s not a common criminal. He took up arms against the United States.”

Graham is not alone in that view. In August, he joined Sens. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.), John McCain (R-Ariz.), and Jim Webb (D-Va.) in sending a letter to President Obama expressing concern over reports that the Administration may try Khalid Sheik Mohammed and other alleged war criminals in civilian courts. The senators urged the administration to try them in military commissions instead, saying in part:

The individuals detained at Guantanamo Bay are not held because of violations of domestic criminal law. They are detained because they have been found to be members of al-Qaida or other terrorist organizations, and have taken up arms against the United States of America. The forum for their trial should reflect the fact that these detainees were captured as part of a military operation and face trial for violations of the law of war. As a result, we urge you to prosecute these suspected war criminals by military commission at Guantanamo Bay. The bill, H.R.2847, is pending in the Senate as an amendment to an appropriations bill.

On Tuesday, former Attorney General Michael Mukasey made a similar argument against allowing the 9/11 defendants to be tried in a civilian federal court in an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal. Mukasey warned that the costs and burdens of security would be enormous, that housing suspected terrorists in U.S. prisons would threaten national security, and that a public trial would elicit sensitive evidence that would compromise intelligence sources and that terrorists will later use against us.

Those sorts of arguments outrage many legal experts and former military officers, who say that only a public trial in a U.S. federal court that affords terror suspects the same rights as all ordinary criminal suspects will carry the legitimacy necessary for such an important trial. And they dismiss the claims that housing terrorists in U.S. maximum security prisons, where terror suspects have been imprisoned for many years, would create any danger at all.

“The federal criminal justice system has adjudicated nearly 200 cases involving international terrorism in the year shortly before and since 9/11,” said Gabor Rona, International Legal Director of Human Rights First, which opposes the use of military commissions to try any Guantanamo detainees. “The idea that it cannot handle classified evidence, evidence from abroad, evidence obtained in the context of armed conflict, all of those have been proven false by the existence and the adjudication of all of those case in the federal criminal justice system, and many of those cases feature precisely those problems.”

“The bulk of resistance to bringing Guantanamo detainees to the U.S. is simply uninformed,” Rona continued. “The ‘not in my backyard idea,’ which I think is a crazy notion of people fearing that they’re going to have to be sitting next to a member of al-Qaeda when they go into Starbucks, is just nuts. We’re not talking about releasing suspected or known terrorists into the streets. We’re talking about transferring them to highly secure correctional and detention facilities for purpose of trial. If they’re found not guilty or guilty and they serve sentences, they’re still not entitled to be in the U.S., they will be deported. I think the administration is confident, and should be confident about being able to convey that this is not a situation that involves risk to Americans.”

Some former military officials hope the president will see it that way as well. On Tuesday, a group of retired generals sent an open letter to Congress, kicking off a campaign to close Guantanamo Bay and have the detainees brought to the United States for federal court trials.

“With 145 convicted international terrorists being held in our prison system, there has been no escape from a supermax correctional facility in the United States,” said retired Lt. Gen. Robert Gard, Chairman of the Center for Arms Control and Nonproliferation, on a conference call with reporters on Tuesday. “It does not threaten the security of this country to move however many of the remaining 226 detainees that we cannot farm to other countries or try and incarcerate, to move them from Guantanamo into our supermax facilities. The claim from members of Congress that this threatens American security is shameful and without a basis.”

Still, even some civil libertarians believe it would be legitimate for the administration to try the Sept. 11 suspects in military commissions at Guantanamo Bay or on U.S. military bases. “Our view is that as a legal matter, the 9/11 conspirators, unlike some other detainees at Guantanamo, could be tried in either federal court or military commissions,” said Kate Martin, director of the Center for National Security Studies. “Then it’s a matter of policy considerations.”

Although Martin says a defendant could get a fair trial in a military commission, that’s not necessarily the case under the current Military Commissions Act, even if recent amendments passed by the Housewere adopted. “One of the hallmarks of a fair trial is that it’s public,” and the military commissions have so far severely restricted public access. “If they choose the forum based on an interest in keeping parts of the trial secret, then they will lose their legitimacy right there,” she said.

Some military commission critics claim that one reason some Republicans support using military commissions is to keep hidden any evidence that the detainees were tortured by U.S. authorities, which the defendants or their lawyers would almost certainly present in their trials.

“There is a second objective in everything that someone like Mukasey is saying,” said American Civil Liberties Union attorney Denise LeBoeuf, who directs the John Adams Project, which organizes defense lawyers to represent the Guantanamo detainees. “That is covering up the details and the identities of torturers. This country had a systematic system of torture through the military and through contractors. Some of those people objecting to federal court trials now either implemented it, or knew about it and should have said something,” she said, adding that some are still in the administration and have an interest in preventing the information from surfacing.

Indeed, according to Justice Department memos revealed earlier this year, Khalid Sheikh Muhammed was waterboarded 183 times. Details of his treatment would likely come up in his defense, if he were to present one. On the other hand, he has confessed and even boasted to having masterminded the attacks numerous times, and has said he does not want a lawyer and wants to be martyred. He still could bring up his treatment by U.S. authorities in a trial, however.

LeBoeuf and other lawyers involved in the defense of high-level detainees say they’ve heard rumors that the administration wants to try the 9/11 detainees in federal court, but it’s impossible to know for sure what U.S. officials will do until they issue their decision.

To LeBoeuf, the fact that the 9/11 case is so high-profile is a strong reason for trying the suspects in public, in a civilian federal court in the United States.

“When you say the whole world is watching a case, this is the one,” LeBoeuf said. “This is the one where the administration has the greatest urgency and pressure to do it in a fair court. It’s also the one where there are mountains of evidence — for both sides. It’s the most investigated crime in the history of the United States. If you can’t put this case into a federal court, then what case can you?”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Hajra Shannona is a highly experienced journalist with over 9 years of expertise in news writing, investigative reporting, and political analysis.

She holds a Bachelor's degree in Journalism from Columbia University and has contributed to reputable publications focusing on global affairs, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

Hajra's authoritative voice and trustworthy reporting reflect her commitment to delivering insightful news content.

Beyond journalism, she enjoys exploring new cultures through travel and pursuing outdoor photography

Latest Articles

Popular Articles