Army Data Shows Constraints on Troop Increase Potential

If President Obama orders an additional 30,000 to 40,000 troops to Afghanistan, he will be deploying practically every available U.S. Army brigade to war, leaving few units in reserve in case of an unforeseen emergency and further stressing a force that has seen repeated combat deployments since 2002.

Jul 31, 20208.8K Shares2.9M Views

Army Gen. Stanley McChrystal (defenselink.mil)

If President Obama orders an additional 30,000 to 40,000 troops to Afghanistan, he will be deploying practically every available U.S. Army brigade to war, leaving few units in reserve in case of an unforeseen emergency and further stressing a force that has seen repeated combat deployments since 2002.

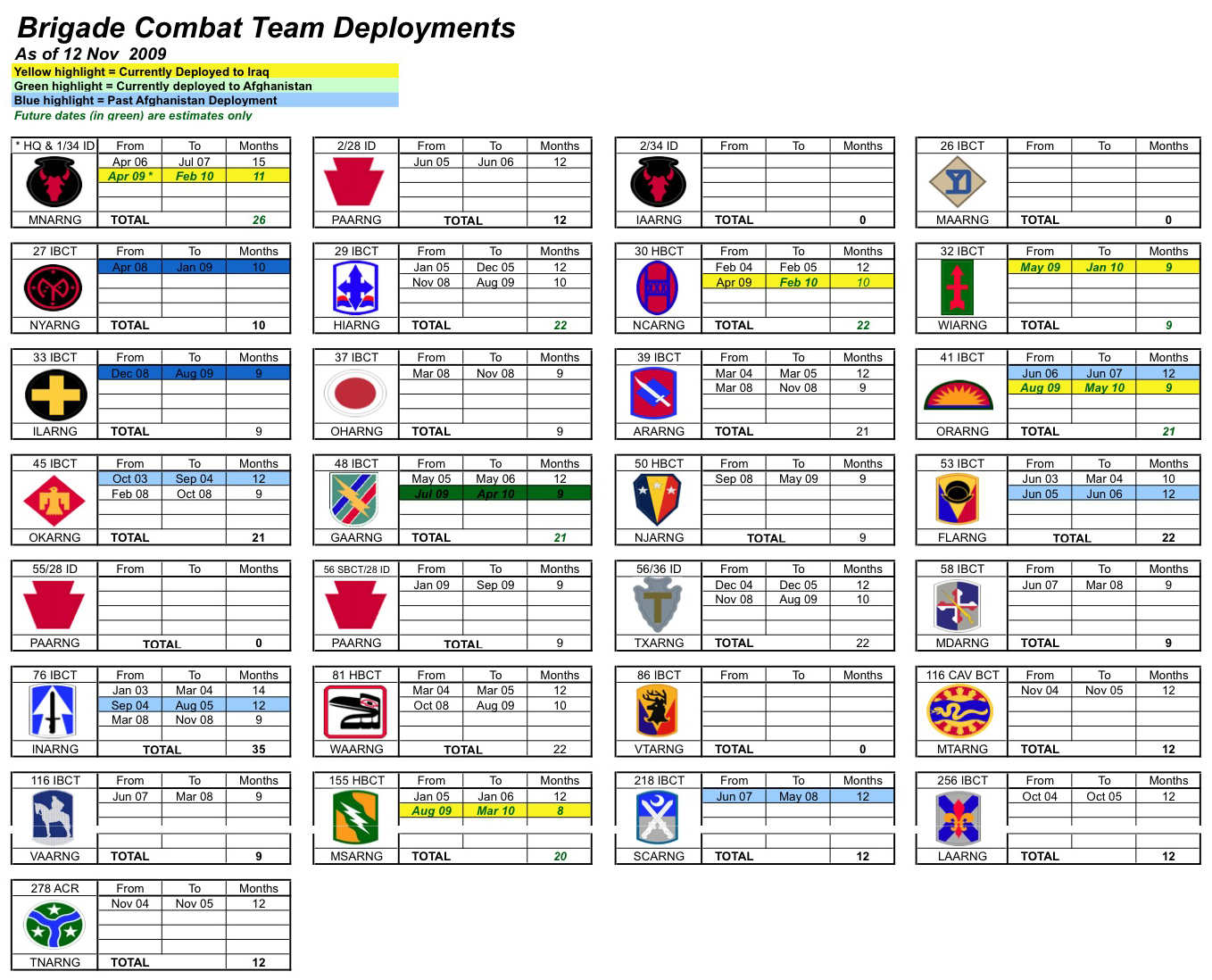

According to information compiled by the U.S. Army for The Washington Independent about the deployment status of active-duty and National Guard Army brigades, as of December 2009, there will be about 50,600 active-duty soldiers, serving in 14 combat brigades, and as many as 24,000 National Guard soldiers available for deployment. All other soldiers and National Guardsmen will either be deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan already or ineligible to deploy while they rest from a previous deployment.

[Security1]Obama is expected to announce a decision on an escalation of troop levels for Afghanistan shortly after returning from his trip to Asia on Friday, which would be the second such escalation of his young presidency. That decision follows a request issued in September from Gen. Stanley McChrystal, commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, in which McChrystal delivered the Obama administration with a palette of different troop-level options to turn around a faltering war effort. While White House officials have cautioned reporters that Obama has made no final choice on the size of a troop increase, a widely re-reported McClatchy story claimedthat the administration was likely to send 34,000 additional troops to Afghanistan, which would raise U.S. troop levels in the eight-year war to an all-time high of 102,000. It is likely that Obama would include members of the other military services, especially the Marines, in any troop increase, but the vast majority of any new troop complement will come from the Army.

The shortage of available combat brigades means that an escalation of between 30,000 and 40,000 troops is “not realistic,” said Lawrence Korb, a former senior Pentagon official in the Reagan administration who now studies defense issues for the liberal Center for American Progress. To send practically all available soldiers into one of the two wars would leave the U.S. with “no reserve in case you had a problem in Korea.”

Click to Enlarge: Army National Guard combat brigade deployment data. (Source: U.S. Army)

Obama would have something of a cushion, but not much, in the early months of 2010. An additional five brigades will finish their 12 months of so-called “dwell time” at home between deployments by April 2010, providing an additional 22,600 troops, but by that time, about 10,200 troops will be scheduled to leave Afghanistan, leaving available a net gain of 12,400. More brigades become available in the summer and fall, although others currently in Afghanistan will be ending their scheduled deployments then as well. Under current Pentagon policy, dwell time for the National Guard varies, but can be no shorter than two years, and so it is possible but not certain that two National Guard brigades composed of 6,800 National Guard soldiers might be available for deployment by March 2010 as well, beyond the 24,000 theoretically available now. Pentagon leaders had hoped to extend dwell time this year, but that was before McChrystal’s request for additional troops.

Click to Enlarge: U.S. Army combat brigade deployment information. (Source: U.S. Army)

Furthermore, not all brigades are the same. Some are built around heavy equipment like tanks, while others are primarily light, mobile infantrymen. According to a September report by the Institute for the Study of War, a pro-escalation think-tank in Washington, no so-called “heavy” brigades have been sent to Afghanistan to date, a condition likely owing to Afghanistan’s lack of paved roads, high elevations and uneven rural terrain, all of which are inhospitable to tanks and other heavy vehicles. But of the 14 brigades available as of December 2009, five of them are heavy brigades, according to the information provided by the Army to TWI, accounting for 19,000 of the available 50,600 active-duty soldiers. There is precedent in Iraq for re-tasking heavy brigades as light brigades by deploying them without their heavy vehicles, as the Institute for the Study of War’s report points out. But there is no precedent for such a thing in Afghanistan. If the Obama administration decides not to re-task heavy brigades as light brigades, the pool of active-duty soldiers immediately available for Afghanistan shrinks to 31,600 soldiers.

Andrew Krepinevich, the president of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, a defense think-tank in Washington, told TWI that an escalation of between 30,000 and 40,000 troops required an inescapable calculation of risk. “The worst thing in the world is to have these people over there getting shot at, not being able to make progress, and the situation [in Afghanistan] just sort of gradually eroding, so it’s that versus the risk of breaking the force, [or] the risk that you’re not prepared for another contingency,” said Krepinevich. “So how do you weigh those risks? There is no formula or algorithm that’s going to give you the answer. It’s going to have to be a judgment call.”

McChrystal wrote in a late August assessment that the U.S. faces a “decisive” moment in Afghanistan. “Failure to gain the initiative and reverse insurgent momentum in the near-term (next 12 months) — while Afghan security capacity matures — risks an outcome where defeating the insurgency is no longer possible,” McChrystal wrote nearly three months ago. While deployment times vary, no brigade can be deployed to Afghanistan overnight, raising questions about how much time remains to turn the war around even if McChrystal gets the 40,000 troops that various news accounts have stated — without official confirmation — that the general wants.

Krepinevich testified on Tuesday before a House Armed Services subcommittee in favor of McChrystal’s proposed counterinsurgency strategy, and appeared to lend support to a troop increase of roughly 40,000. He said that recent steps taken by both the Bush and Obama administrations to increase the total size of the Army and Marine Corps would mitigate against prolonged deployments. “Even if Gen. McChrystal’s request is honored by the president, the combined total of our forces in Afghanistan and Iraq would still be significantly below the levels reached during the Surge,” he told the panel.

But the 2007 troop surge in Iraq was a one-time increase of five combat brigades that ended with those brigades’ tours. By contrast, a troop increase to implement McChrystal’s counterinsurgency strategy is more likely to be a sustained escalation lasting beyond the tours of the initially deployed brigades. And the brigades themselves called upon to implement the troop increase will have already served numerous deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan. Of the 14 active-duty brigades that will be available for deployment in December, five have already served three tours abroad since 2002 and four have already served two. If either the 3rd brigade of the 101st Airborne Division or the 1st brigade of the 10th Mountain Division are asked to deploy to Afghanistan, it will be their fifth tour since 2002.*

Krepinevich said the stress on soldiers called upon to serve repeated tours was a problem for a troop escalation. “You really have to start worrying about greater incidents of post-traumatic stress disorder, [and] that we’re already seeing in terms of the the NCO corps,” he said, referring to non-commissioned officers like sergeants who play crucial leadership roles in enforcing soldier discipline and standards. “Yes, they’re experienced but they’re just so worn out. And that has to be a concern.”

That concern was echoed by Bing West, a Reagan-era senior Pentagon official who traveled to Afghanistan in October. “There is near-unanimous agreement that deployments on the lines over eight months are too long,” West reportedfor the blog Small Wars Journal on Nov. 1, citing interviews with “dozens” of soldiers and Marines. “Aggressive patrolling decreases as the length of tour increases. The troops wear down.”

Korb — who, like Krepinevich, supports the Afghanistan war — said a more realistic troop increase for Afghanistan would be 10,000 soldiers until the drawdown of troops from Iraq “begins in earnest.” There are currently 120,000 U.S. troops remaining in Iraq, almost twice the total in Afghanistan, though Gen. Raymond Odierno, the commander of U.S. troops in Iraq, told Congress in Septemberthat he plans to reduce that total to around 50,000 by August 30, 2010. Alternatively, Korb said, Obama could speed up the pace of redeployment out of Iraq in order to relieve the stress on the force, a point echoed by Krepinevich in an interview with TWI. But under current Pentagon policy, soldiers would still need to receive at least 12 months of recuperation time back in the U.S. before potential assignment in Afghanistan.

The chief of staff of the Army, Gen. George Casey, whose institutional role includes protecting the health of the force, endorsed a troop escalation earlier this month. “I believe that we need to put additional forces into Afghanistan to give Gen. McChrystal the ability to both dampen the successes of the while we train the Afghan civilian forces,” he toldNBC’s “Meet The Press” on Nov. 8. The chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, Adm. Michael Mullen, also has responsibilities for balancing the needs of the Afghanistan war with those of the overall military and threats to the U.S. worldwide. He toldCongress in September that more troops were “probably” needed in Afghanistan as well.

Defense Secretary Robert Gates, a key swing vote in the Afghanistan debate, has told Congress earlier this year that he would seek to lengthen dwell time for the Army in the coming years. In January, he testifiedthat he and Army chiefs wanted to extend dwell time to 15 months at home for every 12 months deployed by October 2010, but in July, he revised that planand indicated that the Army might be able to shift to 15-month dwell times by summer 2010. But Gates reiterated in July a commitment to ultimately giving soldiers at least two years of dwell time by 2011. The Army public-affairs officer who released this information to TWI clarified that no unit was available unless it had ended a previous deployment by at least November 2008, indicating a continued 12-month dwell time policy.

That proposal was devised before McChrystal’s request for additional forces, and it is unclear how the fulfillment of that request will impact the dwell-time policy, if at all. Spokesmen for both Gen. McChrystal and Sec. Gates did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

*Update, 4:35 p.m., Nov. 19: Maj. Stephen Platt, public affairs officer for the 3rd brigade of the 101st Airborne Division, writes to inform me that the brigade has indeed been scheduled to deploy to Afghanistan in “early 2010″ for what will be its fifth combat tour since 2002. I missed a press release from the Pentagon in July announcing the deployment, and word of the upcoming tour was not included in the information provided to me by the U.S. Army. I appreciate Maj. Platt’s clarification.

Camilo Wood

Reviewer

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles