Health Care Primer: A Snapshot of the Toughest Fights Ahead

As hard as the Senate debate promises to be, many of the thorniest conflicts will likely be re-contested when Democratic leaders in both chambers meet to iron out the differences between their bills.

Jul 31, 202021.2K Shares2.1M Views

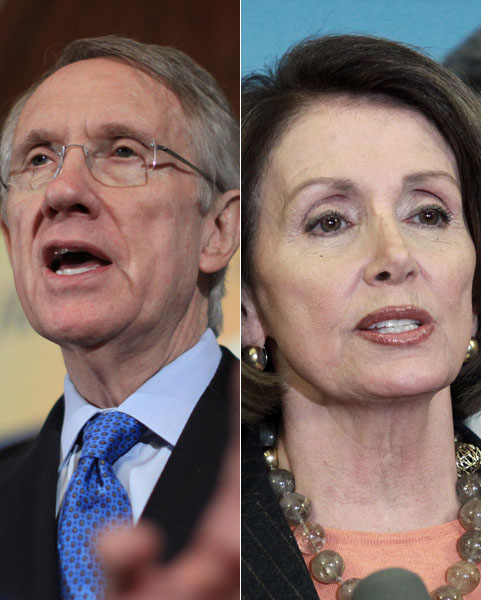

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (WDCpix)

Senate Democrats will return to Washington Monday to begin a long-awaited floor debate on the health-reform bill they hope to pass before Christmas. But it’s hardly the last battle they’ll be forced to wage on the health-care front.

As tough as the upper-chamber debate promises to be, many of the thorniest conflicts will likely be re-contested when Democratic leaders in both chambers meet, probably in January, to iron out the differences between their bills. The legislative disparities revolve around such high-profile topics as the public option and coverage of abortion, but also include lesser-noticed issues, like whether to honor a White House deal with the pharmaceutical industry and how to approach the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Senate Republicans are also eyeing many of these hot-button issues, with hopes of using them to divide the Democrats in order to kill the larger bill. But with the considerable House-versus-Senate discrepancies awaiting conference negotiators, fending off opposition from Senate Republicans in the meantime could prove to be the least of the Democrats’ troubles as they attempt to pass the most consequential health-care reforms in generations.

**Who Pays?

**

Chief among the differences between the Democrats’ bills is how each chamber has proposed to pay the considerable cost of covering tens-of-millions of uninsured Americans. The House pays the freight largely with a 5.4 percent tax on the nation’s highest earners — individuals making more than $500,000 per year, and families pulling in more than $1 million.

The Senate, on the other hand, has proposed an excise tax on the highest-cost insurance plans — those exceeding $8,500 for individual coverage and $23,000 for families. The Senate bill would also apply a 0.5 percent Medicare payroll tax to individuals earning more than $200,000 and families earning more than $250,000.

Liberals and labor unions have supported the House approach, arguing that an unprecedented tax on insurance plans would erode decades of work to secure comprehensive, employer-sponsored health-care coverage for workers. Conservatives, meanwhile, are warning that higher taxes on the wealthy will only exacerbate the nation’s economic troubles in the middle of an employment crisis.

**Coverage vs. Care **

Both the House and Senate bills rely heavily on a Medicaid expansion to cover the country’s poorest uninsured residents. The House would extend eligibility to 150 percent of the federal poverty level (net income), while Senate eligibility would expand to 133 percent of poverty (gross income).

The more significant difference, though, revolves around Medicaid reimbursement, which is so low in some states that many doctorsand dentistsnow refuse to see Medicaid patients. The House bill recognizes the problem, bumping up Medicaid payments for primary care services to 100 percent of Medicare rates by 2012. Despite an effort to get similar language into the Senate legislation, a controversial funding proposal kept the provision out of the final bill.

The reimbursement increase doesn’t come cheap. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the provision would cost $28.7 billion over the next five years and $57 billion over the next 10.

**Abortion **

Rep. Bart Stupak (D-Mich.) lit a firestormearlier in the month when he amended the House bill to prohibit abortion coverage under subsidized exchange plans. The Senate bill would also ban federal funding of abortions, but would allow women receiving exchange-plan subsidies to segregate their premiums and co-payments in order to access abortion services. Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) has already saidthat he’ll offer the Stupak provision on the floor, though supporters will have the difficult task of rallying 60 votes to pass the measure.

Indeed, the Stupak provision is poised to cause more havoc in the House than the Senate, with some House liberals vowingto oppose the larger bill if the language survives the conference negotiations, while Stupak and other anti-abortion Democrats are hinging their support on the provision remaining intact. Satisfying both camps for the sake of the bill’s passage will likely require some delicate wording from Democratic leaders.

**Illegal Immigrants

**

Both chambers propose to screen exchange-plan applicants to ensure that illegal immigrants don’t receive the federal subsidies available to those living below 400 percent of poverty. The Senate bill, however, goes a giant step further, proposing to exclude illegals from purchasing even unsubsidized insurance coverage on the exchange. That provision has riled a number of lawmakersand immigration advocates, who are wondering how allowing folks to buy insurance coverage from private companies with U.S. dollars could harm the country, fiscally or otherwise.

“It makes no sense for anybody,” said Jonathan Blazer, public policy attorney with the National Immigration Law Center. “Nobody’s willing to defend it on policy grounds.”

If the Senate language emerges from the conference negotiations, it will likely lead to a showdown with House members of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, who early in the debate had threatenedto vote against the House bill if it excluded illegal aliens from unsubsidized exchange coverage.

CHIP

Though largely unmentioned throughout the health reform debate, the House bill would terminatethe Children’s Health Insurance Program at the end of 2013, shifting those kids into Medicaid or private plans on the exchange. House leaders — who had championed CHIP for the past 12 years — say their proposal will expand coverage by getting kids and parents under the same plan.

But some children’s health-care advocates have raised alarmsover that strategy, arguingthat the private plans will likely be more expensive, thereby discouraging low-income parents from getting their kids any coverage at all. And Sen. Jay Rockefeller agrees. The West Virginia Democrat — who successfully amendedthe Senate bill to reauthorize CHIP through 2019 — is vowingto fight to keep the program intact.

“Health care reform should improve the coverage children have,” he said, “not take their coverage away.”

Rockefeller, though, has been a lonely voice in support of preserving CHIP, leaving the ultimate fate of his amendment in question.

The Big Deal with Big Pharma

In June, Democratic leaders in the White House and Senate caused a stir when they announced a dealwith the pharmaceutical lobby. Under that bargain, the drug companies promised $80 billion over the next decade to close Medicare’s drug-coverage gap (partially) if the lawmakers agreed to oppose efforts to empower states to negotiate drug prices for residents enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid. The Senate bill keeps that agreement intact, with Finance Committee members shooting downan amendment allowing such price haggling for the sake of closing Medicare’s donut hole altogether.

House Democrats, on the other hand, have said all along that they weren’t a part of the discussions with the drug makers, and they don’t feel bound to any deal they never agreed to. As evidence, the House bill allows states to negotiate drug prices on behalf of their lowest-income seniors — a provision the CBO estimates would save more than $42 billion over the next decade.

The Public Option

At the heart of the debate over health-care reform this year has been the public option — a strategy, popular among liberals and consumer advocates, to create a public, non-profit insurance plan to compete with private companies. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) surprised many political observers last month when he proposedto create such state-based plans in the bill he weaved together from the different proposals passed by the Finance and health committees. Reid’s bill would empower the plans’ administrators to haggle directly with doctors, hospitals and other health-care providers over reimbursement rates, but it would also leave states the option not to participate.

The House bill is similar, but creates a national insurance option rather than numerous state-based plans. Additionally, the House bill doesn’t include the state opt-out language.

Unlike the other topics mentioned here, the toughest fight over the public option seems destined to occur on the Senate floor, rather than in conference. Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.) has repeatedly vowed to filibuster any bill that includes a public plan, whether it’s opt-out, opt-in, trigger-based, or any other configuration. Meanwhile, some upper-chamber liberals — including Sens. Bernie Sanders(I-Vt.) and Roland Burris(D-Ill.) — are hinging their vote for the health reform package on the inclusion of a strong public option.

“This legislation cannot simply be a huge subsidy to private insurance companies that will get millions of new customers and be able to raise their rates as high as they want,” Sanders saidin a statement last week. “I strongly suspect that there are number of senators, including myself, who would not support final passage without a strong public option.”

All of this, of course, could change. Although the House passed its health-care reform bill earlier in the month, the Senate proposal is just hitting the chamber floor today. The upper-chamber is expected to debate the measure through most of December, with hundreds of amendments likely to be offered from both sides of the aisle.

Democratic leaders hope to pass the bill out of the Senate before the holiday recess, pushing the conference negotiations to sometime in January. That 2010 is an election year won’t make those discussions any smoother.

Camilo Wood

Reviewer

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles