Obama Administration Prepares Iran Sanction Options

Any sanctions would seek to curb Iran’s nuclear program.

Jul 31, 2020101.4K Shares1.9M Views

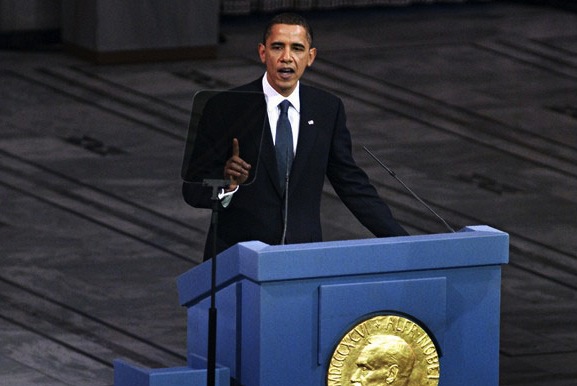

President Obama accepts the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo on Dec. 10. (Guido Ohlenbostel/Action Press/ZUMA Press)

A year’s worth of diplomatic outreach to Iran is on the verge of eclipse, thanks to consistent Iranian refusals to accept President Obama’s offers for a new relationship. As a result, Obama administration officials and their international partners are preparing a package of economic sanctions against Iran for 2010. They prefer to work through the United Nations Security Council, but are prepared to work around it if necessary. Absent a major diplomatic breakthrough in the next few days,new sanctions are considered a near inevitability.

Two senior administration officials, Undersecretary of the Treasury Stuart Levey and Undersecretary of State William Burns, have for months quietly assembled working groups across the government to determine what a sanctions package might contain. The groups examine Iranian vulnerabilities across a variety of economic sectors, “everything from energy to IRGC [the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, an influential and ideological branch of the Iranian military] to financial sector” activity, said a knowledgeable U.S. official who requested anonymity to discuss the unsettled contours of administration policy. The House of Representatives last week approved a bill giving Obama new authority to enact additional unilateral sanctions on Iran’s energy imports.

[Security1]The goal of the new sanctions will be “what is doable” in terms of attracting international support, the U.S. official said, and what “can change Iranian behavior,” particularly over Iran’s nuclear program, which the United States and its allies fear is designed to yield a nuclear weapon.

The U.S. has placed a variety of trade sanctions on Iran ever since a largely anti-American regime came to power in Iran in 1979. Those sanctions have failed to moderate or influence Iranian behavior, largely because they are uncoordinated with Iran’s trading partners — something the Obama administration wishes to rectify with new multilateral sanctions. As much as Obama has said he wanted to explore a new relationship with Iran, Obama said also that even unsuccessful good-faith diplomatic outreach would help bring reluctant nations in line with more punitive U.S. measures. “If we show ourselves willing to talk and to offer carrots and sticks in order to deal with these pressing problems — and if Iran then rejects any overtures of that sort — it puts us in a stronger position to mobilize the international community to ratchet up pressure on Iran,” he said in Israel in April 2008.

In late November, the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Board of Governors voted to censure Iran for its lack of transparency over the program, a move seen as a prelude to a concerted international sanctions effort. Both China and Russia, the two permanent members of the U.N. Security Council least traditionally inclined toward punitive measures on Iran, voted for the censure.

Unless the Iranians unexpectedly accept a deal pushed by the U.S. and its allies before the end of the year to reprocess most of its uranium into a form unsuitable for a weapon, the sanctions push will begin in February, when France, whose government has harshly criticized Iranian nuclear intransigence, assumes its presidency of the Security Council. Still, it is unclear whether the United States and its allies will be able to secure Chinese and Russian support for the sanctions. “The administration is more optimistic than in the past and thinks we’ve moved them in the right direction,” said a U.S. official, who still declined to predict that the two countries would support sanctions.

According to both U.S. and European diplomats, a move in the Security Council authorizing sanctions — or even merely condemning Iran on its nuclear activities — would clear the way for a coalition of nations to enforce a sanctions package. A European diplomat who spoke on the condition of anonymity said the Security Council resolution itself was as important as convincing Iran’s major trading partners to back sanctions.

“Iran’s trade partners, particularly the EU, will add their own layers of sanctions,” the diplomat said. “Some countries will want at least a Security Council resolution to take their own sanctions,” naming South Korea, Japan and the United Arab Emirates. Those countries, along with the European Union, China, India and Russia, make up the vast majority of Iran’s international trading partners.

Among the most controversial of Obama’s positions in the 2008 presidential campaign was his pledge to pursue diplomacy without preconditions with traditional U.S. adversaries like Iran. That effort included at least one private letter from Obama addressed personally to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme Iranian leader, but was met only with rebuke. Administration officials had said throughout 2009 that they were pursuing a “dual track” approach to Iran — diplomatic outreach, combined with more punitive measures in the event outreach was unrequited — but the U.S. official admitted it was bitter to come to terms with Iranian rejection.

“It was disappointing,” the official said. “But the thing is that after the June 12th election, everyone was pretty skeptical.” The regime’s willingness to steal the June presidential election not only made it unlikely that it would accept a more productive relationship with the international community, the official continued, but “people were generally much less excited about engagement because it was so much more unsavory.”

Iranian dissident leaders have been vocal about their rejection of new international sanctions, fearing that the regime will use them as an excuse for additional pressure on the opposition. In response to a question from TWI about Iranian popular rejection of the sanctions, Rep. Howard Berman (D-Calif.), the chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, conceded that sanctions would harm the Iranian people but did not believe that harm should prevent the U.S. from sanctioning Iran. “The notion that you are going to have effective sanctions that don’t impact on the Iranian people, I don’t understand what that means,” said Berman, who sponsored a bill that overwhelmingly passed the House Tuesday giving Obama authority to place new unilateral sanctions on Iran.

But the U.S. official conceded that even sanctions focusing on the finances of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps could still have deleterious and problematic effects on the Iranian people. “It’s a fair critique,” the official said, since sanctions are “an imperfect tool.”

Even if the still-undesigned sanctions package attracts widespread international support, it is still unclear how it would compel the Iranian leadership to give up any unacknowledged ambition for nuclear weapons, and the U.S. official said it also unclear at this point what the Obama administration would consider a successful outcome. The European diplomat framed military action against Iran in opposition to the sanctions, not as their inevitable successor. “Some are afraid sanctions are a first step toward a more confrontational mode, but in fact all Europeans have the view that sanctions are a way of avoiding escalation,” the diplomat said. For years, the Israelis have threatened to attack Iran over its nuclear program.

But the Obama administration has not fully given up on the idea of a diplomatic breakthrough. “Sanctions without outreach – and condemnation without discussion – can carry forward a crippling status quo,” Obama said when accepting the Nobel Peace Prize on Dec. 10. “No repressive regime can move down a new path unless it has the choice of an open door.”

Obama did not specifically mention Iran in his speech, but the speech nevertheless gave a window into the administration’s thinking. “The door will always remain open,” the U.S. official said. “Sanctions are not an end onto itself. They are a means to an end of changing Iranian behavior and the administration is very aware of the trap of falling into a situation where sanctions become the goal and we forget the real goal.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Hajra Shannona is a highly experienced journalist with over 9 years of expertise in news writing, investigative reporting, and political analysis.

She holds a Bachelor's degree in Journalism from Columbia University and has contributed to reputable publications focusing on global affairs, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

Hajra's authoritative voice and trustworthy reporting reflect her commitment to delivering insightful news content.

Beyond journalism, she enjoys exploring new cultures through travel and pursuing outdoor photography

Latest Articles

Popular Articles