Untested Military Commissions Face Challenges

These are all still open issues, said Lachelier. There are so many moving parts.

Jul 31, 2020159.6K Shares2.8M Views

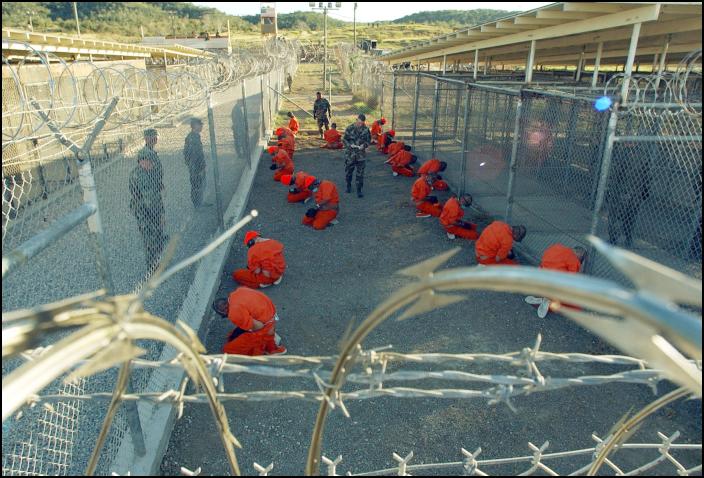

Donald Rumsfeld called the Gitmo detainees "the worst of the worst." (Wikimedia Commons)

In February 2004, Ubrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was charged withconspiring with al Qaeda in Afghanistan, Pakistan and elsewhere to attack and murder civilians and destroy property. The government claimed that al Qosi was an armed guard and driver for Osama bin Laden going back to 1996, provided logistical services and supplies for an al Qaeda compound in Kandahar, and traveled to to Kabul to fight with an al Qaeda mortar crew near the front lines.

Al Qosi was never tried on those charges, however, because in 2006 the U.S. Supreme Court declared the military commissions unconstitutionaland a violation of the Geneva Conventions. Congress re-created the commissions with a new law later that year, and Al Qosi was charged again in 2008.

[Law]Then in January, just after President Barack Obama took office, he suspended the 2006 military commissionswhile he decided what to do with them.

Now, about a dozen military commissions cases that were left in limbo are being revived. And, the government is sending more suspected terror cases for trial there – either at Guantanamo Bay, where they’re currently located, or in Thomson, Illinois, where they could be moved.Judging from recent protests against sending the suspected co-conspirators of the September 11 attacks to civilian trials, some might think that convicting terror suspects in a military commission would be easier. But the new Military Commissions Act, passed by Congress in October and signed by the President, is an untested military system that, like its earlier incarnations, is ripe for constitutional challenge. Whether it will provide the swift justice the Obama administration and others hope for remains to be seen.

The case of al Qosi, now being heard before the new military commission, highlights the sorts of problems that lawyers say are likely to come up in many military commissions trials. Most importantly, they include a range of constitutional challenges to the new military commissions law itself, from whether its jurisdiction inappropriately extends beyond war crimes to include ordinary criminal acts, to whether the law’s permissiveness about the use of hearsay evidence against terror suspects violates their rights to confront and cross-examine the witnesses against them.

Although the case has been pending for almost six years now, at a hearing earlier this month, the government announced for the first time that it wanted to add more charges against al Qosi alleging he participated in a conspiracy with al Qaeda dating back to 1992. That’s also the date that Osama bin Laden allegedly began urging others to attack the United States, according to a U.S. criminal indictment of bin Laden. If the government can show that al Qosi participated in the conspiracy dating back to that time, then he could be held responsible for all of the crimes it committed between 1992 and 2001, when he was captured.

“That’s the way the conspiracy charge works,” said Andrea Prasow, senior counterterrorism counsel for Human Rights Watch, who attended the military commission hearing at Guantanamo Bay in al Qosi’s case earlier this month. “You don’t need to have participated in all of the acts that the conspiracy carried out.”

Advised of the four years’ worth of new charges only hours before the government sought to add them, Navy Cmdr. Suzanne Lachelier, al Qosi’s lead military defense lawyer, protested, calling them “sweeping changes” that would require al Qosi’s defense team to travel to Somalia, Ethiopia and Chechnya to prepare for a trial.

At the hearing, the judge rejected the government’s request to add more charges to the current case against al Qosi, but said it could withdraw the case and refile it with those new claims. If prosecutors do that, however, it will only highlight one of the tenuous bases for the new military commissions, which is its broad jurisdiction.

The crimes the government wants to add in al Qosi’s case did not even take place in the United States or against it. But under the new Military Commissions Act, they can be considered part of a larger conspiracy to attack the United States, and al Qosi’s support for al Qaeda in that period can be considered a war crime.

“It’s absurd in these circumstances,” said Prasow. “But in a conspiracy, the action that the defendant has to take doesn’t need to be criminal. It can be cooking for people, as long as you have a meeting of the minds of all the participants. The government will argue that joining al Qaeda is a meeting of the minds, and a joining of the intent to carry out bad things.”

“We are breaking new ground,” conceded Navy Cmdr. Dirk Padgett, the military commissions prosecutor, at the hearing, according to a blog post Prasow wrote from the hearing at the time. Prasow says the prosecutor defended his bid to reach back to 1992 because “the planning, the conspiracy began years before.”

But are conspiracy to attack and providing substantial support for those attacks even war crimes prosecutable by military commission? That’s not at all clear.

Lachelier last year moved to dismiss the case against al Qosi on the grounds that neither of these charges have traditiionally been considered war crimes, so the military commissions don’t legitimately have jurisdiction to prosecute them.

In fact, that could pose a serious problem for this latest incarnation of the military commissions, as even the Justice Department has acknowledged. In July, Assistant Attorney General David Kris testified before the Senate Armed Services Committeethat “there is a significant risk that appellate courts will ultimately conclude that material support for terrorism is not a traditional law of war offense, thereby reversing hard-won convictions and leading to questions about the system’s legitimacy.”

Congress enacted the Military Commissions Act of 2009 with its broad jurisdiction anyway, and despite senior Justice Department officials’ own doubts, the government is proceeding to prosecute al Qosi for conspiracy and providing “material support” to al Qaeda. Those charges “continue to fly in the face of traditional understandings of law of war violations,” wrote Devon Chaffee, advocacy counsel for Human Rights First, in a blog post she wrote after attending the al Qosi hearing.

Indeed, when the MCA was enacted in October, civil liberties and human rights group objected in large part because it swept into untested military commissions with unknown rules ordinary crimes that have been successfully tried and appropriately belong in federal court.

Now, it’s not clear what is legitimate in the newly reconstituted commissions. “You don’t know what law applies,” Lachelier said of the military commissions. “You pick and choose. You try to draw from international and federal precedent.” How the commissions will use those remains unclear, however.

Another potential challenge to any conviction by the commissions, Lachelier explained, is that the military commissions allow the use of hearsay testimony in circumstances where it would be inadmissible in a federal court. That, too, could become a constitutional problem if convictions are appealed. “The right to confrontation is still significantly diminished in the military commissions,” Lachelier said, referring to the right to the Constitution’s Sixth Amendment right to confront and cross-examine witnesses. If the government claims the witnesses are not available, “these could be trials on paper,” she said.”That’s not what the confrontation clause and the Supreme Court would allow.”

Recently, Lachelier filed four more motions in al Qosi’s case. She claims that the military commission lacks jurisdiction over her client because the prosecutor hasn’t proved he’s an “unprivileged enemy belligerent” — meaning he was a member and substantial supporter of al Qaeda. She also claims that the Military Commissions Act is an unconstitutional Bill of Attainder, meaning a law designed only to punish a certain group of people (in this case unprivileged enemy belligerents), and that it violates the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution because it applies only to aliens (non-citizens).

Many of these claims have been made in military commission cases before. But since this is a new commission with no binding legal precedent, it will have to decide these issues all over again. “The question is, what law applies?” asked Lachelier. “And how will the commission interpret it?”

Ultimately, it may be the Supreme Court that answers these questions, probably several years from now. And if the court holds that Congress and the President overreached in the MCA of 2009, the government’s prosecution of Mahmoud al Qosi, and any other terror suspects charged before the new military commissions, will have to start all over again.

“These are all still open issues,” said Lachelier. “There are so many moving parts.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Hajra Shannona is a highly experienced journalist with over 9 years of expertise in news writing, investigative reporting, and political analysis.

She holds a Bachelor's degree in Journalism from Columbia University and has contributed to reputable publications focusing on global affairs, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

Hajra's authoritative voice and trustworthy reporting reflect her commitment to delivering insightful news content.

Beyond journalism, she enjoys exploring new cultures through travel and pursuing outdoor photography

Latest Articles

Popular Articles