Experts Hope Dems Learn Stimulus Lessons « The Washington Independent

Jul 31, 20201M Shares15.5M Views

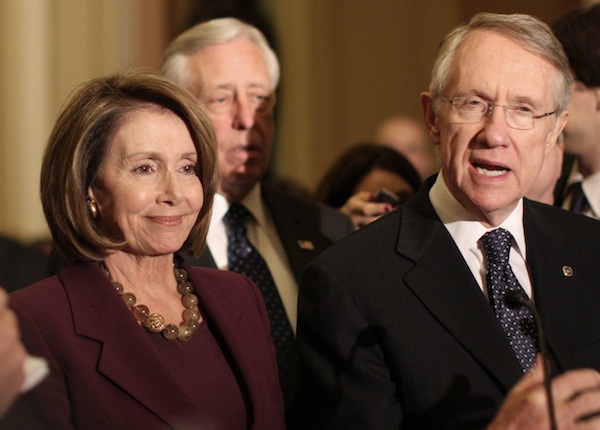

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) (WDCpix)

The failure of Washington lawmakers to recognize the severity of the Great Recession has slowed the recovery and allowed unemployment to reach double-digit levels, according to some of the nation’s leading economists. The experts hope that the latest effort — in the form of a new “jobs bill” being crafted by Democratic leaders — will not only be sizable enough to tackle the problem, but also will focus only on programs providing the most “bang for the buck.”

“In retrospect, they were overly optimistic,” Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a liberal policy group, said of the previous efforts to stimulate the economy. “They just didn’t appreciate the severity of the downturn. … Even now, they don’t seem to get it.”

Image by: Matt Mahurin

Not that lawmakers don’t have some practice at the sport. In February of 2008, with the nation’s unemployment rate at 4.9 percent, President Bush approved$168 billion in direct, $600 tax rebates — much of which, the experts suspect, taxpayers saved rather than spent.

One year later, with unemployment tickling8 percent, President Obama tooka $787 billion stab at the same problem. Many economists maintain that Obama’s stimulus has been heroic in preventing the economy from tanking even further than it has over the past year. Yet, with unemployment now hoveringat 10 percent, they also contend that there is plenty of room for Democrats to improve their stimulus design.

“It is doing what it was intended to do,” said Heidi Shierholz, economist at the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal analysis group. “It just wasn’t big enough. … At the time, we were losing 700,000 jobs a month. There was definitely [the thought that] this $800 billion is not going to do it.”

Also, Shierholz conceded, “There was stuff in there that just wasn’t that efficient as far as spending goes.”

An example, economists say, was the nearly $70 billion to prevent the Alternative Minimum Tax, or AMT, from hitting millions of middle-class Americans last year. That provision might have helped to solve a political dilemma, but it did little to help the ailing economy.

“That crowded out useful stuff,” said Chad Stone, chief economist at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal policy group.

Desmond Lachman, economist at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, was less enthusiastic about last year’s stimulus bill, saying that lawmakers “botched” the effort by allocating too much money to pork-barrel projectssought for political reasons, not economic ones. Now — as Democrats are eyeing yet another large spending package in hopes of curbing the still-rising jobless numbers — Lachman suggested they focus on projects that would get the money out the door more quickly. “You can’t mess it up like you did the last time around,” Lachman said, warning that there’s still a threat the country could slip back into recession.

There were other dubious elements of the $787 billion stimulus bill, economists say. Several billion dollars, for example, went to spur home sales by providing first-time homebuyers with a generous tax credit. Baker, of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, said that provision might have caused a temporary spike in the housing market, but likely won’t increase sales in the long run.

“If you get them to buy in 2009,” Baker said of homebuyers, “that means they’re not going to buy in 2010, or even 2011.”

Yet another stimulus strategy tried by Congress allows businesses to recoup taxes paid in recent years to make up for losses suffered in the recession. Yet research conducted by Mark Zandi, head economist at Moody’s Economy.com, indicates that the so-called “loss-carryback” strategy returns only 21 cents to the economy for every dollar spent by the federal government.

“As far as bang for the buck goes, it’s about the worst you can do,” Shierholz said.

Instead, economists of all political stripes are urging Congress to provide more federal funding for food stamps and Medicaid, while extending unemployment benefits and health coverage under the COBRA program. A simple and well-tested economic rule all but ensures the success of that strategy: Give money to people with little of it and they’ll usually spend it in a hurry.

Indeed, Zandi estimates that expanding unemployment benefits returns $1.61 for every federal dollar spent; increasing food stamps returns $1.74; and direct aid to states — for things like keeping teachers and firefighters employed — yields $1.41.

Baker is also pushing the creation of a federal work-share program, under which employers could reduce the hours of workers rather than laying them off, and the government would make up the difference in lost wages. Workers win, under this plan, because they keep their jobs. Employers benefit because they don’t have to train new part-time workers. And states stand to gain because the resulting payments would be less than the unemployment benefits they’d have to pay otherwise.

There’s some indication that Democratic leaders have already taken some lessons from the shortcomings of the first two stimulus approaches — at least as it pertains to marketing their yet-unveiled bill. For one thing, Democrats have abandoned the “stimulus” label, referring to their latest push instead as the “jobs bill,” lest the public confuse the legislation with the Wall Street bailout.

And another: Democrats haven’t made any grand predictions about the effectiveness of the measure before they even know what’s in it — a departure from last year, when White House economists said the Democrats’ stimulus proposal would keep the nation’s unemployment rate below 8 percent.

“The president’s mistake, and it was a mistake, was to underestimate how bad the situation was we inherited under Bush,” Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) saidthis week. “He should not have said that unemployment would peak at 8 percent.”

Paolo Reyna

Reviewer

Paolo Reyna is a writer and storyteller with a wide range of interests. He graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies.

Paolo enjoys writing about celebrity culture, gaming, visual arts, and events. He has a keen eye for trends in popular culture and an enthusiasm for exploring new ideas. Paolo's writing aims to inform and entertain while providing fresh perspectives on the topics that interest him most.

In his free time, he loves to travel, watch films, read books, and socialize with friends.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles