The ‘Mullen Doctrine’ Takes Shape

Mullen says the military should not be deployed without a complementary civilian effort.

Jul 31, 2020391.5K Shares5.2M Views

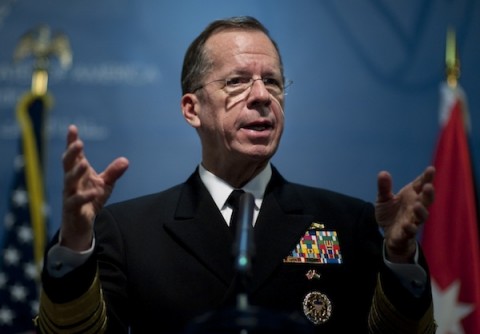

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Navy Adm. Mike Mullen (Defense Department photo)

It’s not the Mullen Doctrine — yet. But in a recent speech that’s attracted little notice outside the defense blogosphere, Adm. Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, offered the first set of criteria for using military force since Gen. Colin Powell held Mullen’s job nearly 20 years ago. And Mullen’s inchoate offerings provide something of an update — and something of a refutation — to Powell’s advice.

[Security1] Mullen’s speech, delivered to Kansas State University on March 3, was not intended to provide an inflexible blueprint for how the U.S. ought to use its military, aides to the chairman said. Instead, the speech meant to draw conclusions from Mullen’s three years as chairman advising two administrations about the scope — and, Mullen’s aides emphasize, the limitations — of military force in an era of stateless and unconventional threats after nine years of continuous warfare.

“This is his legacy,” said Patrick Cronin, a defense analyst with the Center for a New American Security. “He has articulated the Pentagon’s rediscovery of limited war theory.”

Perhaps Mullen’s most provocative “principle,” as he called it in the speech, is that military forces “should not – maybe cannot – be the last resort of the state.” On the surface, Mullen appeared to offer a profligate view of sending troops to battle, contradicting the Powell Doctrine’s warning that the military should only be used when all other options exhaust themselves. Powell’s warning has great appeal to a country exhausted by two costly, protracted wars, one of which was launched long before diplomatic options had run out.

But Mullen’s aides said the chairman was trying to make a subtler point, one that envisioned the deployment of military forces not as a sharp change in strategy from diplomacy but along a continuum of strategy alongside it. “The American people are used to thinking of war and peace as two very distinct activities,” said Air Force Col. Jim Baker, one of Mullen’s advisers for military strategy. “That is not always the case.” In the speech, Mullen focused his definition of military force on the forward deployment of troops or hardware to bolster diplomatic efforts or aid in humanitarian ones, rather than the invasions that the last decade saw.

“Before a shot is even fired, we can bolster a diplomatic argument, support a friend or deter an enemy,” Mullen said. “We can assist rapidly in disaster-relief efforts, as we did in the aftermath of Haiti’s earthquake.”

As much as it seems as though Mullen’s first principle allows for an era of increased conflict, his additional principles flowing from that insight would appear to place constraints on the military. Mullen’s major proposal is that the military should be deployed for future counterinsurgencies or other unconventional conflicts “only if and when the other instruments of national power are ready to engage as well,” such as governance advisers, development experts, and other civilians. “We ought to make it a precondition of committing our troops,” Mullen said, warning that “we aren’t moving fast enough” to strengthen the institutional capacity of the State Department and USAID in order to lift the greatest burdens of national security off the shoulders of the military.

“We shouldn’t start something unless we have the capacity to bring everybody on board,” Baker elaborated, highlighting the “precondition” as among the most important aspects of Mullen’s speech. “I almost read that as more of a cautionary note.” That, at least, is commensurate with the spirit of the Powell Doctrine’s cautions about a national over-reliance on military force. “If you’re going to have anything to sustainable to resolve a conflict, then there’s got to be something that follows,” Baker added, “or you’re going to dump it on the military.”

Stating the position from another — and more controversial — angle, Mullen contended in his speech that foreign policy had become “too dependent upon the generals and admirals who lead our major overseas commands,” an implicit rebuke of the structural factors resulting in the increased diplomatic profile of military leaders like Gen. David Petraeus of U.S. Central Command and Adm. James Stavridis of U.S. European Command. In other words, if State and USAID don’t like being outshined by officers like Petraeus, they need to show a greater assertiveness and capacity to respond to foreign policy challenges before a president turns to the military to solve a problem.

“There is an imbalance in our civilian capacity to work alongside the military in fragile states,” said Cronin, a former senior official at USAID. “The combatant commands are regionally based out in the world, and we don’t have any civilian equivalent of that. So we have to find a way to connect our civilian organization, which is essentially a country team centered on an ambassador, with the interagency represented underneath, with the combatant commander, who has broad swaths of geography and can work across boundaries — which is necessary when you’re dealing with non-state and mobile threats.”

Significantly, Mullen, the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to embrace the theorist-practitioners of counterinsurgency— who contend that the loyalties of a civilian population are decisive in a conflict between a government and internal rebels — offered insights that reflected the worldview of the counterinsurgents. “Force should, to the maximum extent possible, be applied in a precise and principled way,” Mullen said, because the contemporary battlefield is “in the minds of the people.” That’s the first time a chairman has embraced the concept of “population-centric” warfare, a departure from the “enemy-centric” focus of doctrines like Powell’s, with its focus on applying “overwhelming force” to vanquish an adversary. Mullen also implicitly departed from Powell’s conception that war should be conducted with minimal “interference” from civilian policymakers by arguing that the current threats the U.S. faces require an “iterative” process, requiring “near constant reassessment and adjustment.” He said victory in contemporary warfare would feel “a lot less like a knock-out punch and a lot more like recovering from a long illness.”

Mullen is no stranger to offering broad reconsiderations of American strategy. Before becoming chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — the president’s senior military adviser — in 2007, Mullen was the nation’s highest-ranking Naval officer, and in 2006 he embraced a concept called the “thousand ship navy,” a way of thinking about global security partnerships. Mullen definedthe idea as “a global maritime partnership that unites maritime forces, port operators, commercial shippers, and international, governmental and nongovernmental agencies to address mutual concerns” in an October 2006 op-ed in the Honolulu Advertiser. Similarly, using the handle @thejointstaff, Mullen might be the senior military leadership’s most prolific Twitter user.

Some of the counterinsurgents whom Mullen has embraced have grappled with how to interpret Mullen’s speech. Andrew Exum, author of the popular blog Abu Muqawama, tweeted, “Is this speech by Adm. Mullen a big deal or nothing particularly earth-shattering?” Robert Haddick, one of the editors of the influential Small Wars Journal blog, declared Mullen’s speech to have buried the Powell Doctrineby presuming “low-level warfare is an enduring fact of life.” Other bloggers have dissected whether it’s even fair to characterize the speech as a “Mullen Doctrine.”

If it’s not the Mullen Doctrine yet — “That’s your guys’ judgment,” Baker said — it might form the basis for one. Baker said that he would encourage his boss to expand the speech and develop its ideas for a longer essay in one of the major foreign-policy journals. “He felt like he had something to say here,” Baker added, “so he went out and said it.”

Paolo Reyna

Reviewer

Paolo Reyna is a writer and storyteller with a wide range of interests. He graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies.

Paolo enjoys writing about celebrity culture, gaming, visual arts, and events. He has a keen eye for trends in popular culture and an enthusiasm for exploring new ideas. Paolo's writing aims to inform and entertain while providing fresh perspectives on the topics that interest him most.

In his free time, he loves to travel, watch films, read books, and socialize with friends.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles