Will Military Commissions Under Obama Differ From the Bush Era?

It’s going to be a nightmare for the government if they have to constantly close the hearing to talk about things that are embarrassing to the government, says David Frakt, former defense counsel for a juvenile held at Guantanamo Bay.

Jul 31, 2020212.1K Shares3M Views

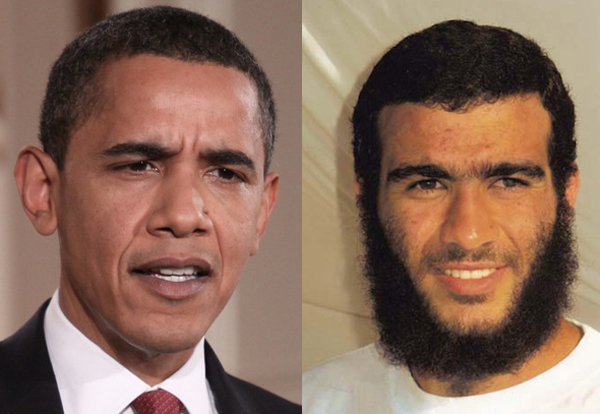

President Obama and Omar Khadr (WDCpix, The Toronto Star/ZUMApress.com)

Starting this week, something will happen that was never supposed to when Barack Obama took the oath of office. A military commission meeting at Guantanamo Bay nearly five months after Obama said the detention facility would cease to exist will hold a pre-trial hearing for Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen captured by U.S. forces in Afghanistan in 2002 and accused of throwing a grenade that killed a U.S. soldier. At the end of the hearing, it will likely be possible to tell whether Obama’s changes to the military commissions created and advocated by George W. Bush — and most congressional Republicans — are substantive or cosmetic.

[Security1]Khadr, a teenager when initially detained, has been held for nearly half his life at a facility that the Obama administration has pledged to close. He will be tried in a legal venue that Obama rejected as a Senator and embraced, in reformed fashion, as president. What happens this week at Guantanamo will determine whether Obama’s pledge that the new, revised military commissions can deliver internationally-recognized justice is meaningful: the pre-trial hearing in Khadr’s case will provide the first in-depth examination of whether Khadr’s treatment in U.S. custody amounts to torture; will determine whether prosecutors can use evidence against him acquired under abusive, coercive circumstances that civilian courts would never allow; and whether additional statements made by Khadr in subsequent and less-coercive circumstances are fair game or inextricable from his overall abuse.

On November 7, 2008, three days after Obama won the presidency, Khadr’s military lawyers introduced a motion to suppress evidence commission prosecutors sought to produce that came from Khadr’s interrogations in Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay. Under the commissions, evidence obtained under torture cannot be used, but the scope of the commissions’ allowance for coercively-obtained testimony remains largely unclear. Since their creation in 2002, the commissions have only produced three convictions, one of which was the result of a plea deal; the Supreme Court has twice ruled that the commissions provide insufficient due process rights for defendants.

Khadr’s attorneys charge that the teenaged detainee underwent over 40 interrogations in 2002 at Bagram Air Field in Afghanistan after being shot and suffering shrapnel wounds in a battle with U.S. forces in July 2002 in the eastern Afghan province of Khost. During those interrogations, Khadr was given limited pain medication; had his head hooded while “interrogators brought barking dogs into the interrogation room”; was placed in stress positions despite his gunshot and shrapnel wounds; and was threatened with rape. After 90 days, U.S. military officials flew him to Guantanamo Bay, where he was again placed in stress positions; had his hair torn out; threatened again with rape; and was even used as “a human mop” by military police after he urinated on the floor of his interrogation room after being placed in stress positions for a prolonged period of time.

Information that emerged from those interrogation sessions — basically, what Khadr told his interrogators while being tortured — comprises a substantial portion of the prosecution’s case against him. It isn’t clear how much of the government’s case against Khadr relies on what he told his interrogators after his abusive treatment. The government will call witnesses who will attest to seeing Khadr throw the grenade that killed Sgt. First Class Christopher J. Speer. (At least one, Sgt. Layne Morris, has come forward in the press.) And the government will probably also seek to introduce statements Khadr made that it maintains were not the result of torture. But Khadr’s lawyers contended in their November 2008 motion that “all statements made by Mr. Khadr subsequent to any statement he made in response to coercive interrogation must also be suppressed as fruit of the poisoned tree,” a legal concept holding that the taint of improperly acquired evidence extends to any secondary evidence it produced.

It’s a crucial question for the military commissions. Every detainee who will be tried before the commissions encountered periods where they were harshly interrogated but then later faced less-coercive interviews, “so this is a real test case for the viability of other prosecutions,” said David Frakt, a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserve judge-advocate general corps who used to be defense counsel for Mohammed Jawad, another juvenile held at Guantanamo Bay. For instance, if Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and the other 9/11 conspirators who were initially held in undisclosed CIA prisons are brought back to military commissions, Khadr’s hearing may determine whether everything they have told their interrogators — even long after being abused — is inadmissible before the commissions. To Jennifer Turner, a human-rights researcher with the ACLU who will travel to Guantanamo Bay to observe the Khadr hearing, if the judge rules that Khadr’s statements to his interrogators can be used against him, “it will show the military commissions under Obama are no different than those under Bush.”

Indeed, it is because of Obama that the issue has remained unsettled. Upon taking office in January 2009, Obama issued executive orders banning enhanced interrogation; vowing to close Guantanamo Bay within a year; and suspending the military commissions while his administration decided how it would deal with the approximately 240 Guantanamo detainees it inherited from the Bush administration. That suspension, coupled with Senator Obama’s objections to the commissions on constitutional grounds, raised hopes among civil libertarians that the administration would ultimately scrap its predecessors’ ad hoc approach to terrorism prosecutions.

Instead, in a May 2009 speech, Obama pledged to reform the commissions, not abandon them. Among the reforms he promised was to “no longer permit the use of evidence — as evidence statements that have been obtained using cruel, inhuman, or degrading interrogation methods.” By October, Congress passed and Obama signed the Military Commissions Act of 2009.Section 948(r) indeed enshrines the ban on statements made owing to those methods. But it gives judges leeway to enter into evidence “other statements of the accused… only if the military judge finds” that they are indeed voluntary.

And that’s where Khadr’s defense motion comes in. While there have been at least two other pre-trial procedural hearings since Obama opted to retain the commissions, none have had the significance of Khadr’s. There are ten days’ worth of hearings scheduled for the prosecution and the defense to tussle over the motion to suppress and what the Military Commissions Act of 2009 requires for it. The Washington Independent will be at Guantanamo Bay for the proceedings, and will provide frequent reports — in blog posts, stories, photo and video — about what they determine for the future of the military commissions in the age of Obama.

There are at least two additional complicating factors. First is that while the commissions have a new law authorizing them, the military has yet to issue a new manual for officers of the court to understand how the procedures under the 2009 law are to be implemented. “If you go to the website for the military commissions,” noted Air Force Col. Morris Davis, a former chief prosecutor for the commissions, “there is no information on who is heading up the military commissions, no information about a new Manual for Military Commissions that implements the changes Congress made in late 2009, and no information about revised Rules for Military Commissions.” As a result, Davis said, “it appears we’re still trying to lay the tracks after the train has left the station, which is no way to run a railroad or a criminal justice system.”

Maj. Tanya Bradsher, a spokeswoman for the commissions, said that “a revised Manual will be issued shortly,” but added that the manual was less important than the law. “The standards for the admissibility of statements are set out in the Military Commissions Act of 2009, and any procedural or evidentiary rules cannot change the standards set by Congress,” Bradsher said.

Frakt said it isn’t that simple. “The military commission rules of evidence have been substantially changed by the Military Commissions Act of 2009, particularly with regard to the standards to be applied to determining the admissibility of a statement,” he said. “The Manual will have significant additional guidance and discussion, because it’s the implementing regulations for this. It’s possible the judge will gather all the evidence and simply sit around and wait for the Manual to come out before issuing a ruling.” In terms of actually arguing the motion, though, “it’s still unclear what rules apply.”

A second complication is how much detail about Khadr’s treatment a judge will allow the outside world to see. There has never before been a two-week court session to examine, in large part, whether the treatment a detainee suffered in a U.S. facility amounts to “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment,” the standard in the Military Commissions Act for inadmissibility. “This will be one of the first really in-depth looks into the treatment of detainees in the early days of the war on terror,” Frakt said. “There are going to be a lot of press and observers [at Guantanamo]. It’s going to be a nightmare for the government if they have to constantly close the hearing to talk about things that are embarrassing to the government.”

Davis, the former chief military commissions prosecutor, holds little sympathy for Khadr, whom the government says a videotape shows emplanting improvised explosive devices in Afghanistan. (The video does not implicate him in the death of Sgt. Speer.) But he said his problem was with the Obama’s claim that it needs to keep the options of both federal courts and military commissions to handle terrorism prosecutions, a claim that struck him as both politically motivated and unjust.

“It’s too bad that the Obama administration is back on its heels in a defensive crouch, afraid to go toe-to-toe with the Cheney right-wing fanatics, and continues to try to have it both ways with the option of military commissions and trials in federal courts still in play,” Davis said. “Hopefully, at some point they’ll grow a pair and make a choice, but this double standard where we’ll give a detainee as much justice as we can and still ensure we get a conviction shows how hypocritical we are when it comes to the rule of law. We talk the talk, but we don’t walk the walk.”

*Correction: *This piece initially stated that there were two plea deals in the military commissions since 2002; there was only one.

Rhyley Carney

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles