America’s Global Outlook, at an ‘Inflection Point’

Ben Rhodes argues that the U.S. must channel our strength and influence to reshaping an international order.

Jul 31, 2020272.7K Shares8.2M Views

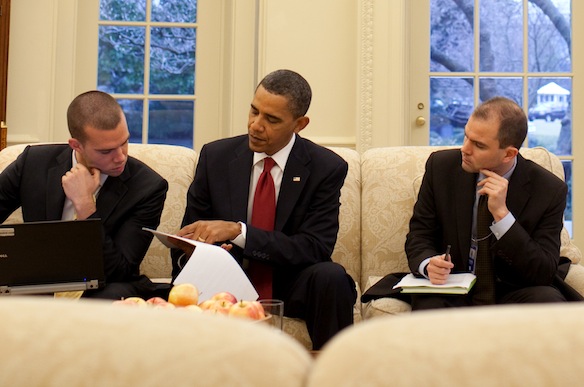

Ben Rhodes, right, in the Oval Office with Director of Speechwriting Jon Favreau and President Obama (White House photo)

“We’re at an inflection point,” Ben Rhodes observed about the United States’ global outlook, a year and a half into the Obama presidency.

Rhodes speaks from a unique vantage point. He’s the deputy national security adviser for strategic communications, a title that obscures his importance as one of President Obama’s closest and most influential foreign policy advisers. He’s been with Obama since the beginning of his presidential campaign, helping shape and explain the contours of Obama’s foreign policy. And he’s the author of the National Security Strategy of 2010, that policy’s foundational text.

[Security1] The Washington Independent spoke with Rhodes about the document, its implications for American national security, and the “inflection point” it addresses. A lightly edited transcript follows.

The Washington Independent: The National Security Strategy pledges, “We must pursue a rules-based international system that can advance our own interests by serving mutual interests.” How do you build a constituency in the U.S. for that, after decades of that system being caricatured — sometimes accurately — as ineffectual?

Ben Rhodes: The tradition in the United States is actually the opposite. Look at the moment of our maximum global power after World War II. We had a clean slate and we chose to build an architecture of international institutions, international standards, international rules, to include the United Nations, to include NATO, to include international financial institutions, treaties, and to apply our power to strengthening that architecture so that it could solve common problems. And I think there was basically a pretty broad, bipartisan consensus that America was served well by an international architecture that could keep the peace and advance prosperity. Sure, there was skepticism about it — there’s always some skepticism about the international order in parts of the American political culture — but I think there’s a broad tradition of support for that because I think the American people are smart enough to know that if we don’t act within that context, we bear a far greater burden ourselves.

**

TWI: So this is a matter of reminding people of what’s worked in the past.**

Rhodes: We’re at an inflection point. We’re clear-eyed about the shortcomings. We’re not starry-eyed about the efficacy of the international system as it is today. As the president has said many times, it’s in some instances buckling under the weight of challenges it wasn’t designed for. However, that presents you with a choice. And that choice is you can say there are emerging challenges like terrorism, like nuclear proliferation, climate, a global economy that’s more interwoven. We can deal with those challenges by saying that the international system is fatally flawed and we’re going to step outside the lines and deal with these issues on our own on an ad-hoc basis. Or you can say we are going to channel our strength and influence to reshaping an international order where we can effectively deal with these challenges.

**

TWI: Secretary Clinton said at the Brookings Institution yesterday that the document’s main takeaway should be its assertion that American power is fundamentally tied to the sources of our strength domestically. But we’re still in the midst of extraordinarily challenging economic times, and there are parts of the dignity promotion section about food security, global health and priorities that previous strategies considered peripheral. Is the agenda too ambitious?**

Rhodes: No, I don’t think so. We’re actually demonstrating this kind of collective action, in our first 15 months, that we’re trying to describe in the actual document. So international economic coordination can no longer be effectively implemented through the G-8, it’s got to be a broader spectrum of nations at the table, to include both China and India, but also your South Africas, your Brazils, your Indonesias, so it’s the G-20. Climate change can’t be dealt with simply by the Kyoto signatories. You’ve got to bring in all major economies, again, to include China, to include India. So that’s the framework we’ve tried to begin through the Major Economies Forum, through the Copenhagen Accord. It includes us, India, China. So we’re already trying to broaden the circle responsibility to deal with these challenges.

There is a rebalancing of the application of American resources that this administration is pursuing that we describe in the document. We’re rebalancing in terms of the capabilities that we apply to our problems, in the sense that we are prioritizing investments and factors like education, clean energy that have been under-resourced over the years. Our commitment to draw down in Iraq and our plans to go over the hump in Afghanistan will represent a long-term rebalancing of our military deployments, which obviously take up a good deal of resources. So we have already begun to see shifts in resources that we project over time.

The second and very important thing, and this gets back to your first question, is an international order that can successfully deal with challenges necessitates less of an allocation of American resources. You were talking about how you make your case to the American people. You make the case to the American people that collective action is far cheaper to America than unilateral action. I mean, that’s just a fact. And if you look at something like the Food Security Initiative, certainly it’s going to take resources, but we pursue that through the G-8 and into the G-20 to try to leverage greater international action.

Similarly, if you look at the thrust of the dignity promotion and the development policies, a lot of it is trying to see capacity in partners. So that we’ll focus development policy on the kind of economic and social progress that we see as a human rights issue as well as a security issue and a prosperity issue. But frankly, by focusing on building the capacity of our partners, we’re trying through our investments to see progress that will diminish the necessity of foreign assistance over time, insofar as we’re building up the ability of nations to not just combat individual diseases, but to develop their own public health systems. We’re not just trying to help them feed their people in a humanitarian emergency, but the premise of the Food Security Initiative is to help them develop the technique and technologies that will allow them feed themselves over time.

So I think again the burden sharing is a critical aspect of the kind of force multiplication that you can get, again, through an effective international order. Similarly, just as we want more responsible action by a broader circle of nations, we want more capable partners, so that over time that’s the means through which we’re managing these problems.

TWI: I noticed some similaritiesbetween the National Security Strategy and the Army/Marine Corps Field Manual on Counterinsurgency, from the focus on legitimacy of action; on taking responsibility for promoting dignity in at-risk populations; and in its recognition that too much hard power can be counterproductive. Did you draw on any of the counterinsurgency lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan when writing the document?

Rhodes: Yeah, absolutely. As the president alluded to at West Point, the war in Afghanistan today is very different in some ways than the war that began nine years ago, as it relates to the nature of the fight and the tactics of the enemy and the lessons that we’ve learned in the application of our power in Afghanistan. And certainly the same would be true in Iraq, that we ended up fighting a war that was different than the kind of war that we, that many people felt like we’d be fighting at the beginning.

So the lessons, I think, we all learned included the importance of the legitimacy of our actions, as it relates not just to the international community but most immediately from the populations of the countries within which we’re operating. So that certainly informs Gen. McChrystal’s approach in Afghanistan, but it informs, again, our approach more broadly, as it relates to Iraq and also other partners that we’re also going to be having to cooperate with on security issues going forward.

TWI: As a strategic communicator, what do you want someone living in Miran Shah, in the tribal areas of Pakistan, who might be caught between the Haqqani network and a government program to degrade that network, to get out of this document?

Rhodes: That the United States is not seeking to control events where they live. Nor do we view their future narrowly through a purely counterterrorism lens. In the first instance, we’re trying to develop the capability in their local area, as well as their national government, to manage the threats within their borders rather than the United States doing so. In the second instance, that we have a broader agenda. We want to speak to their aspirations. America cannot by itself deliver a better life, but it can tilt the scales, as it were, in the direction of greater opportunity, greater human dignity.

We don’t simply have a negative agenda. We have a positive agenda that is focused upon both the capacity of their institutions to manage problems, as well as the dignity that they seek in their own lives.

TWI: If, as the document says, the force of American values is foundational for guiding international cooperation, is there a tension with its embrace of indefinite detention without charge?

Rhodes: Let me take a step back and look at the issues that are touched by this.

We do believe that post-9/11 there were new realities that Americans were going to have to deal with as it related to terrorism and our response to it. Part of the problem is that we have not been able to, as a nation, forge sustainable, durable approaches to dealing with those issues that were effective and that were in line with our values. Now what we’re trying to wrestle with as an administration is the fact that we do need to recognize that there are unique threats that we’re now facing, but that we have to approach those threats and how we deal with them in line with certain principles. And what this administration has said is there may be circumstances where certain individuals who uniquely pose a threat that is demonstrable but that precludes criminal prosecution.

Now, we need to figure out a way to deal with this issue in a way that builds in oversight, that is not simply subject to the decisions of one person or the executive branch, but that is basically embedded in the principles of checks and balances, of oversight, of judicial review, that are at the core of our system. And as the document makes clear at the end, in some of these issues are going to take the actions of all three branches of government, because the executive branch alone can’t make these decisions. That’s been part of the problem in the past. So there needs to be buy-in from the executive branch and from the legislative branch and trying to forge a framework that, again, is durable, that can stand up to the test of our laws, that can protect our security and that, again, can be sustained for future administrations so that we’re not continuing to deal with these issues on an ad-hoc basis but rather within a framework that can absorb the threat of terrorism without overturning the principles of our system.

TWI: Do you expect the guy in Miran Shah to understand that?

Rhodes: I think so. If you are demonstrating that you’re affording rights to individuals and that you are operating within America’s system of checks and balances, of review and oversight, then that’s the case that you make. But I mean, that’s something that we still need to work at as a country. And again, that’s a responsibility that falls squarely on the executive branch but also falls on all three branches of government because this touched on very fundamental but new issues.

TWI: Peter Feaver, who helped write the 2006 NSS, bloggedthat he had some deja vu reading the 2010 version. His document called for “effective, action-oriented multilateralism to address the challenges of the day: to ‘strengthen alliances to defeat global terrorism and work to prevent attacks against us and our friends’ and to ‘develop agendas for cooperative action with the other main centers of global power.’” Is it fair to say there’s some overlap with the 2006 document?

Rhodes: I’d say a couple of things about that. Number one, there’s always certain forms of continuity in American foreign policy. Number two, there were approaches that were pursued in the latter years of the Bush administration that are certainly closer to the approaches that we’ve pursued than some of the decisions that were taken in the first years of the Bush administration.

But number three, there are also clear distinctions in the approaches that this administration has taken. I mean, I don’t think anybody could stack up the priorities that are embedded in this document as it relates to the focus on the domestic economy as a source of our strength in the world; as it relates to how we define our enemy as narrowly as “al Qaeda and its affiliates”; as it relates to our efforts to end the war in Iraq; as it relates to our focus on climate change and clean energy. I could kinda stack up a whole on a whole number of issues.

And that’s not even meant to be a criticism of Peter’s document, which I think is a good document. It’s meant to say that this document uniquely represents the worldview and the priorities of this president and this administration, which are different in some respects from the previous administration. And I also do think that, again, the cooperative approaches that we’re trying to foster are ones that we believe do represent more specifically the challenges of our times: the global economy, the focus we place on our nonproliferation agenda, the centerpiece of our efforts to apply pressure to nations like Iran. So, you know, I think that, sure, there are areas of continuity in American foreign policy, areas of continuity to, again, the latter years of the Bush administration, and then there are areas of increased distinction and different priorities that are natural to any worldview.

TWI: Finally, one of the criticismsI’ve seen of the National Security Strategy is that it doesn’t prioritize amongst its wide-ranging goals. As a foundational text across the national security bureaucracy, how will the government know how to implement the document?

Rhodes: Within the document you have a clear sense of the focus of the administration and how that relates to resource allocation. We’ve sent pretty clear signals about areas that are going to be prioritized going forward, while also recognizing the limits of what any one nation can do around town. Which again gets to some of the rebalancing around our military deployments, it gets to some of the burden sharing that we’re trying to foster, it gets to some of the deficit reduction that’s embedded in health care and other things that we’re doing.

On implementation, the Bush documents are much shorter. We made the decision to encompass what really are our key priority initiatives, so that the things that are listed in here represent our priorities This document can basically serve as a measuring stick that I think we would be happy to turn to in six months or a year or several years and say: How did we do in implementing this part of what we said was fundamental to our National Security Strategy? I think that it does stake out those priority areas that are important to us, that are important to American national security, and that we expect to measure ourselves against going forward. So it starts as a strategy document and then it turns into an implementation document.

Now, aside from that, I think these are actions that need to be taken in concert with other nations. And to try to make them into a list wouldn’t kind of effectively capture the nature of national security in 2010. We are moving in a concerted way on just about everything that is in that document. So I think we’re providing the blueprint.

**TWI: Oh, good, because that allows me to make the Jay-Z reference.

**

Rhodes: Yeah, exactly. *Blueprint 4: the National Security Strategy. *

Dexter Cooke

Reviewer

Dexter Cooke is an economist, marketing strategist, and orthopedic surgeon with over 20 years of experience crafting compelling narratives that resonate worldwide.

He holds a Journalism degree from Columbia University, an Economics background from Yale University, and a medical degree with a postdoctoral fellowship in orthopedic medicine from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Dexter’s insights into media, economics, and marketing shine through his prolific contributions to respected publications and advisory roles for influential organizations.

As an orthopedic surgeon specializing in minimally invasive knee replacement surgery and laparoscopic procedures, Dexter prioritizes patient care above all.

Outside his professional pursuits, Dexter enjoys collecting vintage watches, studying ancient civilizations, learning about astronomy, and participating in charity runs.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles