Did McCain Learn From the S&L Crisis?

The GOP presidential nominee’s role in the Keating Five scandal raises questions about his fitness to handle Wall Street’s meltdown.

Jul 31, 2020115.1K Shares5.4M Views

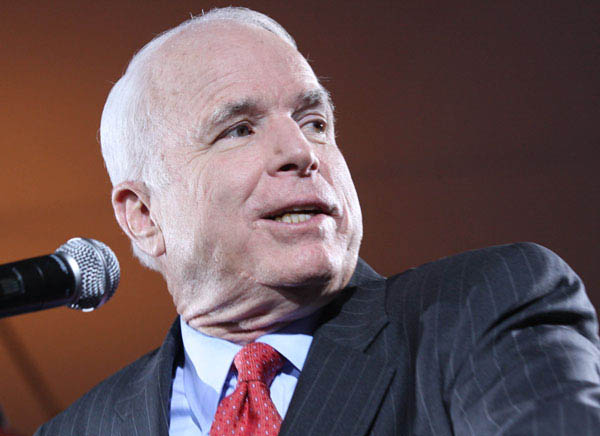

Sen. John McCain (WDCpix)

PHOENIX—In April 1987, William Black watched five U.S. senators, including Sen. John McCain, now the Republican presidential nominee, try to strong-arm federal-thrift regulators on behalf of Charles H. Keating Jr., a Phoenix businessman who owned Lincoln Savings & Loan.

At the time, Black was deputy director of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, which oversees the nation’s thrift institutions. He had joined his boss, Edwin Gray, in the meeting with the five senators, who took turns pressuring Gray to exempt Lincoln from a regulation on how much capital the thrift could directly invest in assets — a regulation Keating vehemently opposed.

Gray’s regulators had found that, by the end of 1986, Lincoln Savings had exceeded the investment regulation by $600 million — and had unreported losses of more than $130 million.

Two years later, press reports about the meeting triggered Common Cause, a non-partisan watchdog group, to request that Congress investigate into whether the senators violated ethics rules by pressuring Gray.

The Senate Ethics committee began an investigation; leading to a high-profile, 23-day hearing in late 1990, during which the media labeled the senators the “Keating Five.” In February 1991, the committee rebuked McCain for exercising “poor judgment” by being at in the meeting — a decision McCain later agreed was appropriate. It was “the wrong thing to do,” McCain acknowledged.

Black, now an associate professor of economics and law at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, said in a telephone interview Wednesday that McCain’s long-standing opposition to regulation of the financial markets and his support for relaxed accounting standards that allow institutions to mask losses makes him unqualified to handle the financial crisis that threatens an economic Armageddon for the country.

“McCain has gotten this stuff wrong from the beginning,” Black said. “One his first acts as a member of the House was trying to stop the re-regulation of the thrift industry” by opposing efforts by regulators to increase capital reserves and reduce the amount of money thrifts could invest, as well as other revisions sought by regulators.

McCain was elected to the House in 1982, and served two terms before moving on to the Senate in 1986. “McCain was very much in favor of accounting forbearance — to game the accounting system,” Black said. “That was his position in 1983. And here we are 25 years later. And he’s learned nothing.”

Black asserts that McCain’s behavior remains unchanged because of McCain’s call last March for a meeting of the nation’s top accountants to relax accounting rules that would allow financial institutions to delay accounting for the decline in value of assets.

Black has been a longtime critic of McCain. He labeled McCain the most culpable of the senators who attended the April 9 meeting in the office of former Sen. Dennis DeConcini, an Arizona Democrat. In addition to McCain and DeConcini, Sens. Alan Cranston (D-Calif.), John Glenn (D-Ohio) and Don Riegle (D-Mich) were also there.

The week before, on April 2, Gray had met with McCain, Glenn, Cranston and DeConcini, who kicked off the proceedings with a reference to “our friend at Lincoln.” Keating had ties to all five senators. He and employees of his companies had contributed $1.3 million to the senators’ campaigns and other related groups, including get-out-the-vote efforts.

All five senators had close relationships with Keating. Keating’s holding company, American Continental Corp., was based in Phoenix and was a major employer there — which drew McCain and DeConcini into his circle. Lincoln Savings, meanwhile, was based in Cranston’s home state of California.

Glenn also viewed Keating as a constituent, because the banker had a business headquartered in Ohio and was a protege of the Cincinnati business icon Carl Lindner. Riegle was a member of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, and Keating had a big hotel investment in Michigan.

Lincoln Savings failed in 1989 because of bad loans and mounting losses in direct investments, ultimately costing taxpayers more than $3 billion. Keating was convicted on 73 federal counts of wire and bankrutpcy fraud in 1993, and spent four years in prison before his conviction was overturned on appeal. Faced with a second trial, he pleaded guilty to four counts of fraud, and was sentenced to time served.

While McCain and Glenn received the mildest rebukes from the ethics committee, Black contends that McCain’s long-term relationship with Keating made him the only senator who stood to personally benefit from getting regulators to back off from Lincoln Savings.

McCain’s wife, Cindy, and his father-in-law had a $360,000 investment with Keating and others in a shopping center at the time of the 1987 meeting. If the Federal Home Loan Bank Board moved to enforce the direct investment regulations on Lincoln Savings, Keating may have had to dispose of that property at a possible loss. McCain has dismissed Black’s self-dealing allegation — stating that he and his wife maintain separate finances through a prenuptial agreement.

But Keating was also a close friend of McCain. The high-flying banker had paid for McCain and his family to vacation with him in the Bahamas on several occasions. McCain paid Keating $13,400 to cover expenses after the 11 trips were disclosed, years later.

Keating and employees of American Continental, which controlled Lincoln Savings, had also contributed $112,000 to McCain’s campaigns. The Arizona senator has said that Keating’s contributions to his first House campaign, in 1982, played an important role in that win.

Black says that the two meetings in April of 1987 were among a series of actions, including opposition to increasing capital requirements and tighter regulation of assets, taken by McCain that helped contribute to the S&L crisis, which ultimately required a $125-billion taxpayer bailout.

In an interview Tuesday with National Public Radio’s “Here and Now”, Black was particularly critical of McCain’s role to support the Reagan administration’s unsuccessful effort in getting two Keating associates appointed to the Federal Home Loan Bank.

“I’ll tell you the biggest thing Sen. McCain — then Rep. McCain — tried to do,” Black said on NPR. “The administration attempted to give Charles Keating control over the federal agency regulating savings and loans. There were three presidential appointees and there were to be two members chosen by Charles Keating. Sen. McCain was not only aware of that effort but supportive of it. Had that occurred, the savings and loan crisis, instead of being $125 billion to $150 billion, would have been over a trillion dollars. It would have probably still been our worst political scandal in history.”

Black said on the phone Wednesday that McCain opposed the bank board’s effort to tighten regulations on the S&L industry, which had grown rapidly after Congress gave thrifts additional lending powers in the early 1980s.

Thrifts began lending to, and in some cases, making direct investments in, risky projects — including racetracks, office buildings in cities with high vacancy rates and undeveloped land. The boom was not accompanied by enhanced supervision, Black said.

By the mid-1980s, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board sounded an alarm: depositors’ funds — insured by the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corp. up to $100,000 — were at risk.

To head off a crisis, the bank board regulators moved to institute tougher accounting standards and increase the amount of capital that thrifts had to hold in reserve. But Congress resisted. According to Black, McCain supported the continuation of accounting rules –- dubbed “Keating accounting” by Black– that allowed thrifts to mask their losses for years by overstating the value of their assets, including intangibles like “goodwill” in the thrift’s net worth.

When the subject of the Keating Five came up in McCain’s interview with WKYC-Cleveland reporter Tom Beres last week, the GOP presidential nominee did not say, as he had previously, that attending that April 1987 meeting with Gray was “the wrong thing to do.” Instead, he insisted the “key” to the episode was that Robert Bennett, the lead investigator of the Senate Ethics Committee, recommended that Glenn and McCain be dropped from the case.

“I had done nothing wrong…I was kept in that investigation for political purposes,” McCain told Beres. “It was a very unhappy period in my life,” McCain continued. “But the fact is that I moved forward, and I have been the greatest voice for reform and against corruption in Washington than anybody.”

But Black said McCain has still not learned the lessons of strong financial regulation and strict accounting standards. As evidence, he points to the senator’s March 25 speech on the housing crisis. McCain called for a national meeting of accounting professionals to discuss changing the “current mark to market” accounting system — that requires lending institutions to price assets at current market value.

“We are witnessing an unprecedented situation as banks and investors try to determine the appropriate value of the assets they are holding,” McCain said, “and there is widespread concern that this [mark-to-market] approach is exacerbating the credit crunch.”

These were terrifying words to the former banking regulator, who had witnessed firsthand the consequences of accounting rules that did not accurately value the assets of thrifts. “McCain’s answer,” Black charges, “is to get the accountants in the room to make sure we create phony capital by not recognizing our losses.”

The current financial crisis and credit crunch, Black said, is the result of a loss of trust in financial markets that began when investors and financial institutions refused to take each others’ word that the prices of their assets were accurate. “Once the trust is lost, it’s very hard to get it back without regulation,” he said. “Why would you trust a fellow banker when you know you are cheating?”

But Black isn’t confident that Congress and the administration will come up with an effective plan to unclog the financial system’s arteries. He is no friend of the Bush administration’s $700-billion bailout proposal. He worries that the government will buy toxic assets at prices far above their market value. “The government gets to be the chump in the market and taxpayers get to bear the losses,” he said.

He also isn’t confident that the crisis will spur widespread regulatory reform and tougher accounting rules. McCain, Black believes, certainly doesn’t understand the need for regulatory reform and rigorous accounting.

“When you deregulate, you just are not losing the ability to find individual losses and frauds,” Black said. “You lose the scouting function that tells you the lay of the land.”

Without knowledge of what may lurk over the horizon, disaster can strike. “That’s when you walk into ambushes,” Black said.

Dexter Cooke

Reviewer

Dexter Cooke is an economist, marketing strategist, and orthopedic surgeon with over 20 years of experience crafting compelling narratives that resonate worldwide.

He holds a Journalism degree from Columbia University, an Economics background from Yale University, and a medical degree with a postdoctoral fellowship in orthopedic medicine from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Dexter’s insights into media, economics, and marketing shine through his prolific contributions to respected publications and advisory roles for influential organizations.

As an orthopedic surgeon specializing in minimally invasive knee replacement surgery and laparoscopic procedures, Dexter prioritizes patient care above all.

Outside his professional pursuits, Dexter enjoys collecting vintage watches, studying ancient civilizations, learning about astronomy, and participating in charity runs.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles