As 2010 Midterms Approach, Politicians Ask Whether Pork Really Brings Home the Bacon

“‘I have the experience, the seniority, I’ve delivered for the state.’ There are nine out of ten elections in which that works. There’s one election in which it wont,” says G. Terry Madonna of Franklin and Marshall College.

Jul 31, 202018K Shares1.2M Views

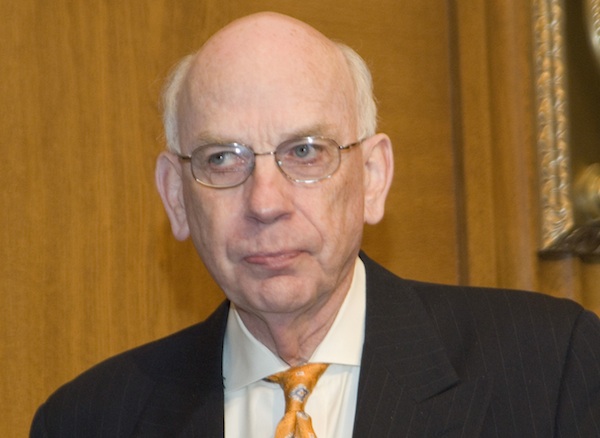

Sen. Bob Bennett (R-Utah) lost in the primary after his opponent criticized his earmark spending. (Vivian Ronay/ZUMA Press)

During Utah’s bruising Republican Senate primary battle, challenger Mike Lee repeatedly attacked longtime incumbent Bob Bennett for his habit of requesting earmarks. But Lee also pledged to fight to keep NASA’s Constellation program — a big source of jobs in Utah — alive through congressional spending. Bennett tried in vain to point out the inconsistency of Lee’s statements, but to no avail. He lost his party’s nomination in June.

[Congress1] The cause for Bennett’s downfall was by no means limited to earmarks — his vote for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which bailed out Wall Street banks, arguably played a much bigger role — but it highlights the increasingly thorny political calculus around the longstanding practice of requesting federal funds for specific projects in one’s state or district. Earmarks represent a minuscule portion of the federal budget. But they are acting as potent weapons in political contests this midterm election season, given the widespread concern about the national debt and the yawning budget deficit.

For challengers, the issue is easy: Pick an earmark, describe it as a waste of taxpayer dollars and paint your opponent as fiscally irresponsible. For incumbents, choosing a response is difficult: Swear off the practice and risk appearing hypocritical for accepting prior funds, argue for specific projects but advocate loudly for reform or double down and brag about the benefits of earmarks.

Once considered as natural in politics as kissing babies, earmarks took increased political significance in the run up to the 2006 midterm elections. When a number of scandals involving Republican lawmakers and the beneficiaries of their congressionally directed funds came to light, Democrats seized upon them as a sign that Republicans were hopelessly corrupt. As a result, Democrats rode a wave of anti-corruption, anti-earmark fervor into office and quickly instituted a number of reforms to make the process more transparent.

In a year where the electorate has acquired — or at least politicians believe the electorate has acquired — a maniacal fascination with spending and deficits, however, earmarks have taken on another sense of importance: tangible signs of at times reckless and wasteful spending that politicians can single out in a time of painful belt-tightening for the electorate.

“The population is feeling really antsy for the first time about the deficit and the debt,” notes Steve Ellis, vice president at Taxpayers for Common Sense. “It’s hard to get your head around big entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security, but it’s easy to talk about a million dollar boondoggle.”

Further amplifying politicians’ fears are the surprising number of incumbents known for being “big providers” for their home states — typically considered the safest kind — who have lost their primary races. Along with Sen. Bennett, Sen. Arlen Specter (D-Pa.) was a longtime member on the Senate Appropriations committee and has since lost his primary election. In the House, Reps. Allan Mollohan (D-W.V) and Carolyn Kilpatrick (D-Mich.) also both sat on the Appropriations Committee — and lost their chance to represent their party this November as well.

All these politicians faced extenuating circumstances ranging from switching parties to the appearance of corruption, but together their fate is making candidates and pundits fear that bringing home the bacon isn’t the same proposition that is used to be.

“The point it that it isn’t a guarantee that it’ll help,” says Ellis. “It’s not as big a positive that people have often made it out to being. If earmarks equal votes, these people would be bulletproof at the ballot box.”

Both Republicans and Democrats in the House moved early to avoid the stigma, adopting measures among their caucus to voluntarily restrict or ban the use of earmarks for fiscal year 2011. Sen. Jim DeMint’s (R-S.C.) efforts to do something similar in the Senate have fallen flat, however, forcing candidates for the august body to chart out their own path on the issue.

One of the first Senate candidates to swear off earmarking was Rep. Paul Hodes (D-N.H), who recently pointed out the fact that he came out against the practice before his likely GOP challenger, former state attorney general Kelly Ayotte.

“The difficulty for Hodes is that he’s at a point where this whole question of who owns the fiscally conservative mantle [in New Hampshire] is really up for grabs right now,” notes Dante Scala, professor of political science at the University of New Hampshire. After the Bush tax cuts, and the Obama stimulus, voters truly aren’t sure, and “he’s trying to say I’m not the typical Democrat. I’m different from that.”

Hodes denies that he stopped requesting earmarks as a political move. Rather, he describes it as the logical conclusion of a reformist who encountered Washington. “I’ve been in Washington long enough to see what’s broken, but not long enough to be contaminated,” he told MSNBC. But Ayotte, naturally, isn’t buying it, and has seized in a press release on his previous earmarks record as a “glaring example of [his] hypocrisy.”

In Pennsylvania, too, candidates face a changed electoral landscape from the one that elected Specter to five consecutive terms, partly on the basis of the infrastructure and health funding he faithfully channeled to the state. “‘I have the experience, the seniority, I’ve delivered for the state.’ There are nine out of ten elections in which that works. There’s one election in which it wont,” says G. Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin and Marshall College, referring to the present midterm election cycle.

Independent voters living in the suburbs — many of whom voted for Obama but now fret about deficits — are the key demographic both Rep. Joe Sestak (D-Pa.) and former Rep. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) are fighting over, notes Madonna, and the earmarks issue is “part of the larger mosaic in which Republicans will try to tie [Sestak] to debt and deficits.”

As a result, Sestak is attempting to walk a fine line, pushing legislation for all earmarks to be scrapped in favor of a system of competitive grants, but in the meantime still advocating for projects in his district.

“Joe is not going to take away the opportunity for projects to help people in his district when there really isn’t the mechanism for funding them otherwise,” says Jonathon Dworkin, his campaign spokesperson. “And as he’s working to change the system to remove political influence, he’ll work [within it] in as transparent a way as possible.”

It hasn’t stopped Toomey, however, from challenging Sestak to sign a pledge to not accept earmarks and arriving on Independence Mall in downtown Philadelphia with a small pig to make the announcement.

“I also want to welcome Porky,” he told the crowd. “Everyone can say hello to Porky, who symbolizes waste that we see in Washington all the time. If he were life size, in that sense, of course there wouldn’t be enough room in Philadelphia for him.”

The backlash against earmarks has at times burned Republicans, as well, however — like Rep. Roy Blunt in Missouri. Running for the open senate seat now held by Sen. Kit Bond (R-Mo.), he’s had to be accommodating to the legendary Missourian’s way of doing things.

“Earmarks have been a tried-and-true method of congressmen serving their constituents as long as the republic has been around and Bond has been really good about making sure central Missouri is getting its slice of the pie,” says L. Marvin Overby, professor of political at the University of Missouri-Columbia. “That makes it difficult for Republicans running in the state, because he is the icon among Republican politics here… so someone like Blunt trying to take his place has to tread carefully around that legacy.”

Indeed, Blunt has stuck largely to the same path regarding earmarks as Bond, refusing to repudiate his own record or Bond’s on the issue, and he’s drawn heat from Tea Party groups and Democrats alike as as result. Blunt edged out a number of tea party candidates who challenged him on the issue in the primary, but he now faces Democrat and Missouri Secretary of State Robin Carnahan, who made a pledge to ban earmarks a central part of her campaign.

“Congressman Blunt has long supported the wasteful earmarking process and, during his tenure in Washington, earmarks have increased seven-fold from just 1,596 earmarks in 1997 to nearly 12,000 in 2008 and costing taxpayers over $228 billion,” Carnahan charged recently. “It is time for Washington politicians like Congressman Blunt to put fiscal responsibility before their pet projects.”

But then there are states like Nevada, where Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid is too entrenched in Democratic leadership and the state’s political machinery to do anything but double down on the issue of earmarks — and brag about it.

“Reid made a comment in which he said something like, ‘It’s not because I’m special, but because of where I’m at, I can do things for Nevada that a new senator cannot. As a political scientist I’m like ‘Yeah, you’re right,’” says Eric Herzik, chair of the political science department at the University of Nevada-Reno.

Reid’s challenger, tea party favorite Sharron Angle, has vowed to not request earmarks for Nevada and pillories him for the practice, but she also often attacks Reid for not doing enough for Nevadans in the same breath.

By all accounts, it’s a bad year to be known for one’s appropriations, but that doesn’t mean the reputation can’t still hold sway among voters, especially in small states with a big chip on their shoulders.

“I think the Nevada electorate is far more accepting of the earmark process because we’re a small state that’s often ignored and here we have a guy who can deliver for us,” says Herzik. “Three states that are historically very accepting of the [earmark] process are West Virginia, Nevada, and Alaska. When you have a senior senator who delivers, often the anti-earmark rhetoric is less successful.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles