The Cost of Jail to America’s Working Population

This week, the Pew’s Economic Mobility Project is up with an astonishing report on the financial damage incarceration does to inmates and the broader economic

Jul 31, 2020460 Shares459.9K Views

This week, the Pew’s Economic Mobility Project is up with an astonishing reporton the financial damage incarceration does to inmates and the broader economic opportunity locked up in America’s prisons. The United States currently jails one in every 100 adults — the highest rate in the world. That costs one in every 15 state general fund dollars, more than $50 billion a year.

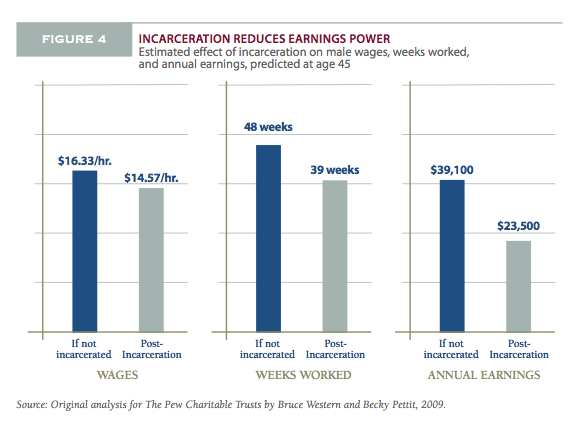

Jail isn’t just costly to the taxpayer. It’s also costly to the inmate. Time in jail reduces an inmate’s earnings 40 percent, on average. It limits their future economic mobility. And it hurts the fortunes of their children — a lot of children, given that 1 in every 28 has a parent behind bars (including one in nine black children).

“On average, incarceration eliminates more than half the earnings a white man would otherwise have made through age 48, and 41 and 44 percent of the earnings for Hispanic and black men, respectively,” the report says. “Of note, these losses do not include earnings forfeited during incarceration; they reflect instead a sizable lifelong earnings gap between former inmates and those never incarcerated.”

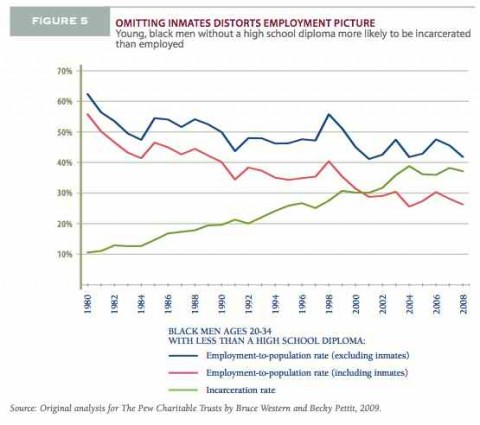

The report also notes that the United States incarcerates so many working-age people — 2.3 million of them — that it distorts the employment and unemployment figures. “[C]onventional methods of assessing employment exclude the men and women behind bars, resulting in an incomplete picture,” the report says. The biggest impact is on the employment-to-population ratio, a way of gauging how economically productive the workforce is. When prisoners are included in the standard calculation, the EPOP changes dramatically. For working-age black men, it falls from 67 to 61 percent. For 20 to 34-year-old black men, it falls from 66 to 58 percent. Jail has become so common for black men, in fact, that they are more likely to be in jail than at work, if they are young and don’t have a high-school diploma.

The flip side of all of this, of course, is that the United States could do a lot of financial good for itself and its citizens if Congress took up prison reform. (Notably, it’s a bipartisan issue, if not a popular one. Fiscal conservatives and social-justice-conscious liberals can get behind it.)

The report has some commonsense recommendations:

- Proactively reconnect former inmates to the labor market through education and training, job search and placement support and follow-up services to help former inmates stay employed.

- Enhance former inmates’ economic condition and make work pay by capping the percent of an offenders’ income subject to deductions for unpaid debts (such as court-ordered fines and fees), and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit to include non-custodial, low-income parents.

- Screen and sort people convicted of crimes by the risks they pose to society, diverting lower-risk offenders into high-quality, community-based mandatory supervision programs.

- Use earned-time credits, a proven model that offers selected inmates a shortened prison stay if they complete educational, vocational or rehabilitation programs that boost their chances of successful reentry into the community and the labor market.

- Provide funding incentives to corrections agencies and programs that succeed in reducing crime and increasing employment.

- Use swift and certain sanctions other than prison, such as short but immediate weekend jail stays, to punish probation and parole violations, holding offenders accountable while allowing them to keep their jobs.

Some states are taking cost-saving reforms into their own hands. Missouri, for instance, gives judgescost-of-sentence guidelines while they are deliberating.

“„For someone convicted of endangering the welfare of a child, for instance, a judge might now learn that a three-year prison sentence would run more than $37,000 while probation would cost $6,770. A second-degree robber, a judge could be told, would carry a price tag of less than $9,000 for five years of intensive probation, but more than $50,000 for a comparable prison sentence and parole afterward. The bill for a murderer’s 30-year prison term: $504,690.

Camilo Wood

Reviewer

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles