Book Banning: Why Take Away Prisoners’ Tiny Solace?

Why would several American prisons resort to book banning? What would they get out of it? Also, what kind of books do they even ban in the first place?

Author:Dexter CookeReviewer:Hajra ShannonDec 16, 202128.1K Shares1M Views

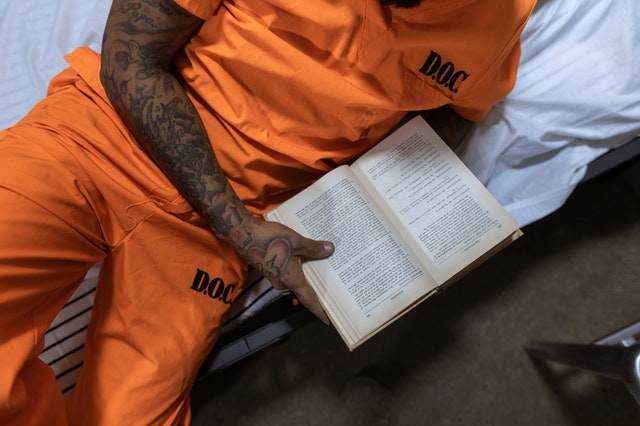

If “books are everything in prison,” as claimed by Robbie Pollock, what happens now if that “everything” gets taken away from prisoners in a book banning spree happening in America?

Pollock, program manager of the prison writing program of PEN America (est. 1922), remarked about the crucial role of books in the lives of prisonersin an April 2021 interview with Iowa Public Radio.

“Books are also dangerous to the status quo,” he added.

That status quo seems to be the force behind the recent book banning in U.S. prisons.

Popular books are banned in U.S. prisons

Book Banning In Prisons

African American slave-turned-U.S. marshal Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) once said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.”

Imagine how literate incarcerated people might react to that quote while serving their sentence in a prison that implements book banning.

In an essay he wrote for Protean Magazine, Pennsylvania-based freelance writer Alex Skopic offered his views regarding the implementation of book banning by different correctional facilities in the U.S.

The Michigan prison system defended its decision by saying that books could be used to hide “‘contraband which poses a threat to the security, good order, or discipline of the facility,’” as quoted by Skopic.

Though Skopic acknowledged contraband smuggling in jails, he argued that it was “a flimsy justification” for book banning and accused jail guards as the ones behind the proliferation of contraband.

Skopic based his allegation from a survey conducted by Prison Policy Initiative, a non-profit organization in Massachusetts working against “mass incarceration and overcriminalization,” according to its Twitter profile (@PrisonPolicy).

Prison Policy Initiative’s 2018 survey revealed that jail staff, not in-person visitors, are the ones who smuggle contraband – apparently to be sold to inmates. In 2018, twenty jail staff from eight different states were arrested for smuggling drugs such as marijuana and meth, cigarettes, and phones.

Speaking of making profit out of cash-strapped prisoners, Skopic identified “profit” as the great motivator behind book banning in prisons.

Prisons normally received donated books. Banning books from public donors will mean that prison libraries will need to buy books. Of course, it’s the jail administrators who will get to choose and approve which retail book vendors their facility would purchase from.

In Iowa, according to Skopic, one prison orders books from two giant bookstore companies: Books-a-Million and Barnes & Noble. He added that they sell books at the manufacturer's suggested retail price (MSRP).

Business as usual.

So, prisoners need to cough up more of their hard-earned money just to buy a single copy.

Skopic said that $20 could only be enough for one book. That amount could already buy “three or four used ones.”

How about e-books?

In 2018, Florida-based I.T. provider JPay gave free tablets to 52,000 inmates at the New York Department of Corrections, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

The non-profit organization Appalachian Prison Book Project (APBP) in West Virginia reported that the Virginia-based telecom companyGlobal Tel Link likewise provided free tablets to West Virginia prisons.

These acts, however, weren’t benevolent at all.

APBP said that based on the Prison Policy Initiative’s report, by 2021, JPay would have pocketed $16 million from its contract – part of which was the free tablets – with the New York Department of Corrections.

The supposed generosity of Global Tel Link, according to APBP, was only a profit-making effort in disguise.

Global Tel Link charges prisoners 5 cents per minute when they read the books uploaded in the tablet they gave.

A “5% commission on gross revenue” awaits the West Virginia Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the one that entered a contract with Global Tel Link.

For Skopic, all these book banning schemes simply lead “to rampant price-gouging and profiteering on an industrial scale.”

Do Prisoners Have To Pay To Read?

From what Skopic and the Appalachian Prison Book Project (APBP) revealed, yes, prisoners have to pay to read, whether it’s an actual book or one from a tablet.

In short, because of book banning, prisoners need money first before they can read something.

“The idea of spending 3 cents a minute on a book was impossible. I didn't have 3 cents,” wrote Chris Wilson in an opinion piece published by USA Today in February 2020.

Wilson – imprisoned at 18 – emphasized that prisoners need money for a lot of things, such as for phone callsand clothing necessities.

A prisoner’s wage in the U.S. for the labor they do varies from one state to another.

In California, prisoners receive as low as 8 cents per hour for a regular/non-industry job, according to a 2017 article by Prison Policy Initiative. That would be 9 cents for Illinois prisoners and 10 cents for those locked up in Idaho.

They’re still lucky, though. Prisoners in Alabama (for a regular/non-industry job), Arkansas, and Georgia don’t receive a single cent at all.

Books Banned In U.S. Prisons

The United States prison system has been guilty of book banning for many years already.

In September 2018, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections told the public to stop mailing books to prisoners, according to Slate. Alex Skopic wrote that Michigan prisons also banned booksthat same year.

In the second quarter of 2019, Book Riot said that Washington and Ohio started book banning.

This year, the Iowa Department of Corrections started to ban people from sending books, reported Iowa Public Radio.

According to Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative, which shares similar aims with Prison Policy Initiative, below are some of the books banned in U.S. prisons:

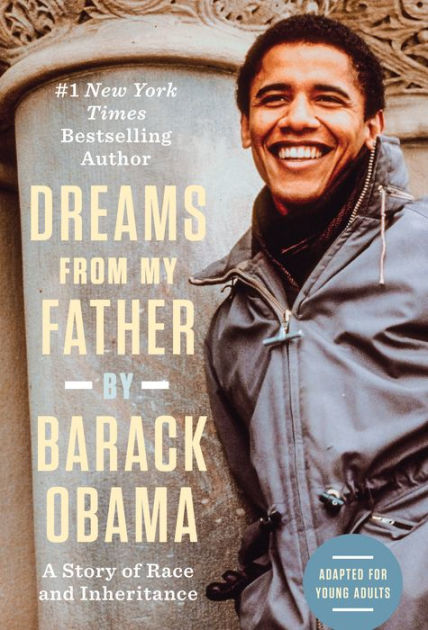

(1) Dreams From My Father (1995, Barack Obama)

(2) Kindred (1979)

(3) Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

(4) She’s Come Undone (1992)

(5) The Bluest Eye (1970)

If you’ve noticed, most of them are classics.

Oh, Mosby’s Medical Dictionary (2005) also made it on the list. Yes, it did.

A New York prison, reported The Guardian in September 2019, banned an atlas of the moon because prisoners might use it as a reference for an escape plan.

In Wisconsin, “100 Years of Lynchings” (1962) got banned, according to Equal Justice Initiative. In Illinois, there are 10,000 banned books, including “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America” (2017).

In 2019, the Danville Correctional Center in Illinois banned “Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant” (2014), reported NPR. In a Kansas prison, “The Hate U Give” (2017) was banned; in New Hampshire, it's “The Lovely Bones” (2002).

Authors whose work got caught up with book banning are mostly Black ones, according to the Equal Justice Initiative. These Black authors include:

(1) Michelle Alexander

(2) James Baldwin (1924-1987)

(3) Octavia Butler (1947-2006)

(4) Alex Haley (1921-1992)

(5) Malcolm X (1925-1965, born Malcolm Little)

Kate Cauley, an assistant professor at The City University of New York, described the American prison system’s book banning as “overly complex and unsound.”

She wrote that in her article, “Banned Books behind Bars: Prototyping a Data Repository to Combat Arbitrary Censorship Practices in U.S. Prisons,” published by Humanities in October 2020.

Cauley said that the “unregulated” book banning could be violating the First Amendment rights of U.S. prisoners.

Banned Books In Florida Prisons

Florida prisons embrace book banning tightly.

Their list of banned books reached over 8,000 titles, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, from 2012 through 2019.

One of them was “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010),” said Cauley.

Some of the others – you might be surprised! – are the following, per online resource Florida Today:

(1) The Wright Brothers: How They Invented the Airplane (1991)

(2) The Zombie Combat Manual: A Guide to Fighting the Living Dead (2010)

(3) Woman: Your Body, Your Health (1989)

(4) Women’s Guide to Household Emergencies (2013)

(5) Writing Winning Business Plans (2005)

(6) YouTube Channels For Dummies

(7) Zenspirations Coloring Book: Birds & Butterflies (2015)

Banned Books In Texas Prisons

According to Kate Cauley’s article, the Texas prison system banned more than 10,000 books.

The New York-based National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) listed the following banned civil rightsbooks in Texas prisons:

(1) A History of Black America (1994)

(2) Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age (2004)

(3) Finding Oprah’s Roots, Finding Yours (2007)

(4) Politics of Rage: George Wallace and the Origins of New Conservatism (1995)

(5) Race: How Blacks and Whites Feel About the American Obsession (1992)

NCAC added that Texas prisons likewise banned these rehabilitation books:

(1) Handbook of Clinical Intervention in Child Abuse (1982)

(2) Men Who Rape: The Psychology of the Offender (1979)

(3) Stopping Rape: A Challenge for Men (1993)

(4) Too Scared to Cry: Psychic Trauma in Childhood (1990)

(5) Why Me? Help for Victims of Child Sexual Abuse Even If They Are Adults Now (1984)

Conclusion

Though he didn’t explicitly express it in his opinion piece for USA Today, it could be presumed that Chris Wilson didn’t favor book banning.

Now “a successful entrepreneur,” according to the American Libraries Magazine, and an author, Wilson partly owed his post-prison successto reading books.

In Wilson’s experience while serving time in jail for 16 years, he said, “The best way for prisoners to fill that time is to read."

"Reading opens up access to instruction across any subject. It teaches job skills. It reminds those left behind that a world exists beyond the cage.”

With book banning, what will happen now to incarcerated people whose only world they know as of the moment is a caged world called prison?

Dexter Cooke

Author

Dexter Cooke is an economist, marketing strategist, and orthopedic surgeon with over 20 years of experience crafting compelling narratives that resonate worldwide.

He holds a Journalism degree from Columbia University, an Economics background from Yale University, and a medical degree with a postdoctoral fellowship in orthopedic medicine from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Dexter’s insights into media, economics, and marketing shine through his prolific contributions to respected publications and advisory roles for influential organizations.

As an orthopedic surgeon specializing in minimally invasive knee replacement surgery and laparoscopic procedures, Dexter prioritizes patient care above all.

Outside his professional pursuits, Dexter enjoys collecting vintage watches, studying ancient civilizations, learning about astronomy, and participating in charity runs.

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Hajra Shannona is a highly experienced journalist with over 9 years of expertise in news writing, investigative reporting, and political analysis.

She holds a Bachelor's degree in Journalism from Columbia University and has contributed to reputable publications focusing on global affairs, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

Hajra's authoritative voice and trustworthy reporting reflect her commitment to delivering insightful news content.

Beyond journalism, she enjoys exploring new cultures through travel and pursuing outdoor photography

Latest Articles

Popular Articles