Royalty Exchange: Can you buy your favorite artist's music rights?

If you haven’t heard about Royalty Exchange, today you will know that you can earn royalties from buying your favorite artist’s music rights. Yes--you can actually buy Miley Cyrus’s music rights and make money when people use the music anywhere else, whether it’s Spotify or TV commercials.

Author:Paolo ReynaReviewer:Iram MartinsJun 30, 2021160.9K Shares2.1M Views

Aside from crypto, stocks, forex, gold, and silver, what else can you buy with your money?

If you haven’t heard about Royalty Exchange, today you will know that you can earn royalties from buying your favorite artist’s music rights. Yes--you can actually buy Miley Cyrus’s music rights and make money when people use the music anywhere else, whether it’s Spotify or TV commercials.

Although not so new, only a few know Royalty Exchange, and those who are in the music field are only the ones who discover how big earnings can be when you find the right royalty source.

Now, here are facts about Royalty Exchange and some analysis on whether it’s legit or not.

What Is The Royalty Exchange?

When consumers look forward to a rising future, the Royalty Exchange gives songwriters, in particular, the ability to commercialize their catalogs now. The allure of prosperity isn't the only thing that attracts investors; the prospect of long-term consistency is also appealing.

According to Antony Bruno, Director of Communications for the Royalty Exchange, royalties are charged on a set schedule. It's not the same as a dividend. You realize it will arrive at a certain period and that the prices are predetermined-they're predetermined and regulated. There's no doubt about what the royalty rate is.

Moreover, the royalty amount would not change if the equity price falls. If bond stocks are down, royalty prices remain unchanged. If you have capital in royalties, you should rely on a royalty report to arrive on a daily basis. When you're aiming at a larger fund, that's a good hedge.

The Market

The eXchange is the place where royalty agreements are made. It's a free, accessible, and inclusive ecosystem that brings together developers and investors according to their own terms.

At any one moment, over 30,000 active investors utilize The eXchange to search for hundreds of royalty offerings and make deals directly to authors and other rights holders, who may approve or counteroffer if they see fit.

The end effect is a frictionless activity that enables both buyers and sellers to see the maximum potential of their concepts.

How Does It Work?

A piece of music has two copies rights: one for the composer and one for the performer. Both can be owned by artists who compose their own music. One is sometimes owned by a record company. Each copyright has many royalty sources associated with it, depending on how the music is used: how often it is heard on the radio, how frequently it is downloaded, whether it is used in a film, whether it is used in advertisements, and so on.

The Royalty Exchange allows artists and songwriters to auction/sell some part of their profits, monetizing potential earnings today. It may be a new means of income for songwriters in particular.

Selling The Royalty Source To Shareholders

Any artist who has a royalty source will offer a part of it to a shareholder. That may be 100%, 5%, or whichever percentage they choose to try to make accessible. They will even offer the share to an individual, who will also be the owner of the royalty stream in the future.

Whatever the artist does not sell, he or she keeps. If the performer is a well-known name, they will go on tour. They would be able to make sponsorship agreements. If they continue to raise funds, they have other options. They don't have the same chances as a songwriter, who is relatively unknown. As a result, they will have to depend on their catalog, which is their only resource.

Royalty Exchange Works Directly With The Songwriter

The Royalty Exchange has sold at auction rights to tracks by Bette Midler, Ariana Grande, and 2Pac, among others. Currently, investors should consider Miley Cyrus' "Wrecking Ball" for development opportunities and invest accordingly.

In general, the Royalty Exchange works exclusively with the songwriter, not with a record company or with the musicians.

Photography, stock video recordings, an audio book, and other ventures have all been completed through Royalty Exchange. However, with over 300 sales in the last two years, they are now concentrating on the music side.

Is It Real Or A Scam?

A Legit Exchange

Royalty Exchange, a venture-backed company established in North Carolina in 2011, was sold to new ownership headquartered in Denver in 2015. Among alternative investing platforms, their public auction concept sticks out.

According to one blogger, who has worked as a book publisher for 20 years and has seen firsthand how most commercial rights deals in the publishing industry are far from straightforward, Royalty Exchange deserves credit for working to improve access and opportunities for both rights holders and consumers.

The Royalty Exchange places itself as the most accessible entry point into a rapidly rising demand for acquisitions in a market that is otherwise unrelated to conventional money.

With this brief information about the company, we can conclude that it exists and it has something to offer to its investors., therefore, a legit exchange. However, that doesn’t mean that it has no risks at all.

Risks Attached To Royalty Exchange

Overvalued Royalty Sources

Unfortunately, owing to the naivete of the market, the simplicity of buying music royalties allows royalty purchasers to significantly overvalued the royalty source.

Someone could, for example, see a royalties swap listing for an independent band that made $7,000 in the previous year and decide that $35,000 is a fair price to pay.

The total price charged was around 5x profits, according to analysis of the ten latest offerings on the royalty exchange platform. While this rationale seems to be rational, it lacks the intense deflation that is inherent in the essence of music.

According to studies of music as a capital asset, 75% of projected copyright revenue happens in the first year after publication, depreciates at a 10% annual pace between years 1 and 5, and then reaches near-zero (i.e. annual royalties of less than $750) from year 6 on.

This suggests that by the moment a royalty is rendered available for sale, the majority of the immediate revenue has already been provided for the holder of the musical commodity, and the dealer is hoping that an ambitious buyer can do an appraisal that overestimates the first-year results to proceed throughout the post-sale ownership period.

Buy-back Option

Where a seller has a "buyback incentive" provision in the selling deal, such as "The seller holds the right to buy this royalty at 125 percent of the purchase price at any point within 5 years of the date of purchase hereof," the seller reclaims the upside thereby shifting all liability to the buyer.

A buyback opportunity essentially eliminates even the remote chance of profiting from music royalty investments. The holder of the royalties would be on the road to owning the near-immediately depreciated 75 percent income stream, so if anything occurs to show that a significant profit can be made, the seller will jump back in and take advantage of the opportunity.

A buyback incentive is fantastic for a seller because it allows you to recover possession if the asset sold turns out to make high returns down the line. If it doesn't, you've already received your money and don't have to pursue the decision.

However, there are just a few appealing scenarios for buying from the buyer's perspective. It's technically likely that royalties could skyrocket for all of the factors mentioned above, and the seller will refuse to use the buyback incentive, but depending on the other side of a deal, being clueless is not a wise investing technique.

Types Of Royalties Provided By Real Exchange

Royalties From Copyright

Although the nuances differ from sale to sale, you're essentially participating in a potential revenue stream resulting from copyright fees, mainly for music. Any auctions, for example, are for the "production" rights to a catalog of music, such as TV, satellite radio, or Pandora streaming.

Royalties From Synchronization And Mechanical Sales

Other privileges come from "synchronization," such as whether one of the songs is used in a television program, a film, or an advertisement, or from "internet sync" on YouTube. Other royalties come from "mechanical" purchases, such as the actual selling of a CD or vinyl album or the use of an on-demand subscription service (like Pandora or Spotify).

Permanent Royalties

A performance society (such as ASCAP or BMI) collects royalty and distributes the funds to the rights owner.

Such profits are for perpetual royalty, and most are for a fraction of a catalog’s sales. Other purchases are only temporary, act as an incentive for the artist, and only grant the seller tax rights for a set period of time, such as the next ten years, before reverting to the initial rightsholder.

Multiple bidders may buy stock in a catalog on the Royalty Exchange, particularly if they are greater than the standard selling the auction system supports.

Rights deals can be complicated, but investors can make sure they know just what they're getting and just how long they're getting it.

What Do You Actually Get From It?

Royalty Investments

Royalty investments are contracted guarantees on potential royalties due to a copyright holder who has agreed to license out any or more of the claim. The bidder would only have access to the per rata share bought if the sale is for a limited or diminished amount of royalty rights.

Investors are charged a $500 buyer payment via Royalty Exchange. Buyers will pay $4,500 to become an "All Rights Investor" to avoid the $500 charge, as well as get other perks such as priority bidding and access to additional details.

After a profitable bid, Royalty Exchange receives a commission from the copyright buyers. The auction material includes information about any extra costs.

Making Money From Royalty Investments

Royalty payments are usually rendered periodically or semi-annually, either directly through ASCAP or BMI, or by Royalty Exchange. The number of returns varies widely based on the catalog. Older royalty streams have a tendency to stay consistent over time, with some room for development.

Since certain copyright rights last for the author's lifespan plus 70 years, certain revenue sources have the ability to last for a long time. Other royalties can be available over a set period of time, like ten years. The duration of the rights would be specified in the relevant listings.

Testimonies

The success of the company can be seen through its partnership with big music and production brands.

Last March 2021, Royalty Exchange partnered with Vydia, a well-known digital distributor. According to Lydia’s CEO, "This relationship helps us to give indie labels and musicians an option to secure a major label contract after they achieve popularity with a viral hit." "These musicians have already shown that they know how to smash a song, but this capital gives them the ability to push their careers to the next stage."

There are a few other closed auctions that looked like a much better bargain for the performer than for the investor.

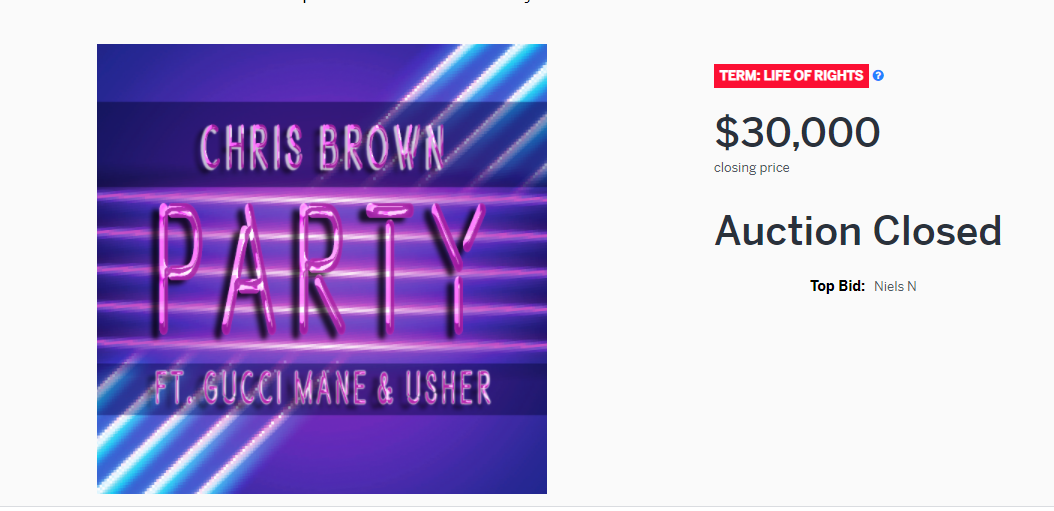

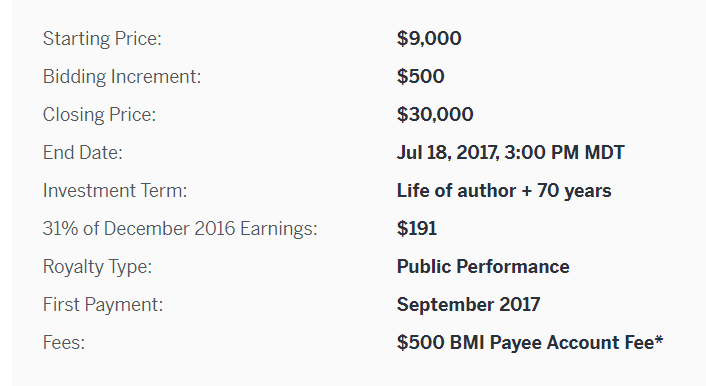

For example, songwriters Christopher Dotson and Floyd E. Bentley III previously received $40,000 and $30,000, respectively, for their portion of royalties from Chris Brown's single "Party" —despite the fact that the song was only published in December 2016 and netted the pair only $544 in royalties at the time of the auction, meaning that the commodity hadn't yet proved itself in the marketplace.

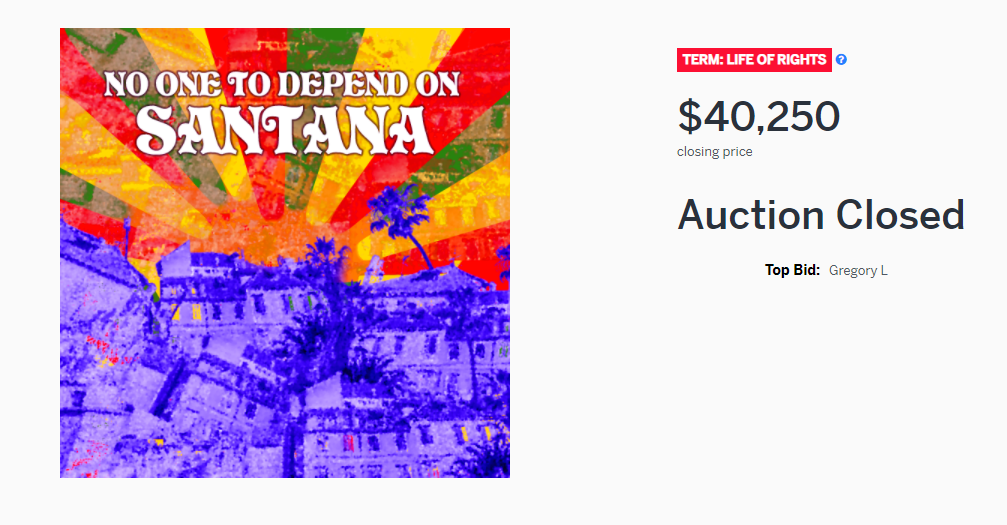

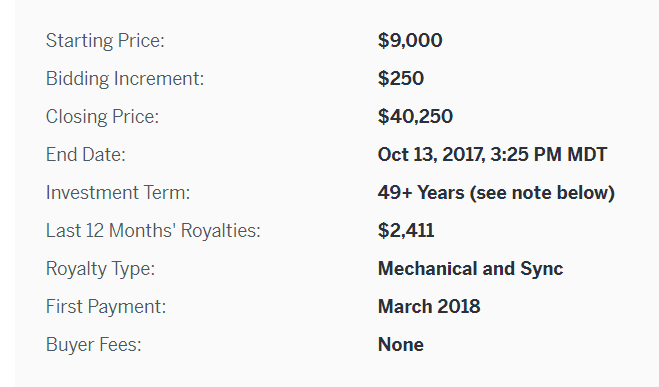

In another case, an investor charged a 17x multiple on the 12-month royalty profits from Santana's "No One To Rely On" drummer Thomas "Coke" Escovedo's portion, despite the fact that revenues have been declining since 2008 and 97 percent of sales have come from only one of two songs in the catalog, indicating a lack of diversification.

Example

Enation was an indie rock band established in Battle Ground, Washington in 2004. Until 2012, Michael Galeottiwas the keyboardist in the band. Unfortunately, he died away. Not only was he known as the ex-husband of actress and singer Bethany Joy Lenz, but he was also referred to as such.

Wrapping Up

Like any other investment, Royalty Exchange doesn’t always guarantee results. There are success and failure stories behind the praise of people. If you plan to invest in music soon, make sure you have enough knowledge about what you are venturing into. You are investing your hard-earned money and you deserve to know if you are going to earn it or not. Be a wise investor! Or, if you plan to sell your music right, be a wise seller!

Paolo Reyna

Author

Paolo Reyna is a writer and storyteller with a wide range of interests. He graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Media Studies.

Paolo enjoys writing about celebrity culture, gaming, visual arts, and events. He has a keen eye for trends in popular culture and an enthusiasm for exploring new ideas. Paolo's writing aims to inform and entertain while providing fresh perspectives on the topics that interest him most.

In his free time, he loves to travel, watch films, read books, and socialize with friends.

Iram Martins

Reviewer

Iram Martins is a seasoned travel writer and explorer with over a decade of experience in uncovering the world's hidden gems. Holding a Bachelor's degree in Tourism Management from the University of Lisbon, Iram's credentials highlight his authority in the realm of travel.

As an author of numerous travel guides and articles for top travel publications, his writing is celebrated for its vivid descriptions and practical insights.

Iram’s passion for cultural immersion and off-the-beaten-path adventures shines through in his work, captivating readers and inspiring wanderlust.

Outside of his writing pursuits, Iram enjoys learning new languages, reviewing films and TV shows, writing about celebrity lifestyles, and attending cultural festivals.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles