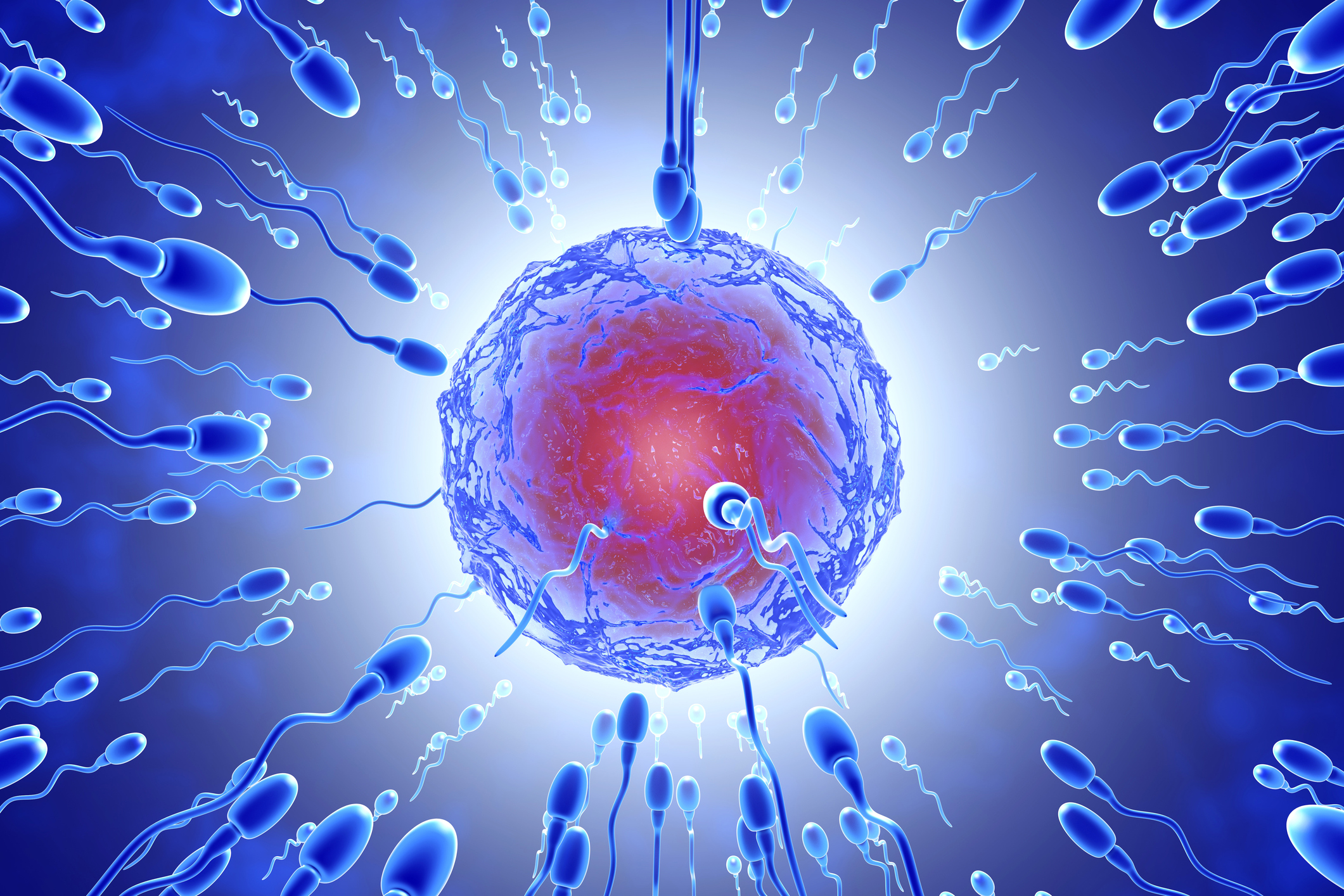

Clusters Of Cooperating Sperm Outpace Solitary Sperm In The Mating Race

A new study reveals that bull sperm move more efficiently in groups, which may have implications for understanding human fertility. A team led by physicist Chih-kuan Tung and colleagues found that this behavior improves the likelihood that clusters of cooperating sperm outpace solitary sperm in the mating race in simulated reproductive tracts of animals like cattle and humans.

Author:Camilo WoodReviewer:Dexter CookeOct 12, 20227.4K Shares493.3K Views

A new study reveals that bull sperm move more efficiently in groups, which may have implications for understanding human fertility. A team led by physicist Chih-kuan Tung and colleagues found that this behavior improves the likelihood that clusters of cooperating sperm outpace solitary sperm in the mating racein simulated reproductive tracts of animals like cattle and humans.

Despite common belief, the advantages of clustering are not solely a function of increased processing speed. Tung of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro claims that "they are not faster." According to the author, they move "In terms of speed, they are comparable or slower" as sperm that is on its own.

It's not the fastest sperm that win, but the ones that can stay on target, like a race between a group of tortoises and an individual hare. Since the shortest route between two sites is a straight line, the fact that sperm, when left to their own devices, take circuitous routes, is problematic.

Conversely, sperm that congregate in groups of two or more use more direct pathways when swimming. This phenomenon was first seen by the same team of scientists when they followed sperm as they swam in a stationary fluid. However, this would only benefit clusters of sperm if they happened to be moving in the desired direction.

The researchers didn't realize the full potential of sperm clustering until they built an experimental setting that included fluid flow. To reach the ovum, sperm in mammals like humans and cattle must swim against a mucus current that flows from the cervix and away from the uterus.

Clustering's potential benefits are hard to investigate from within live organisms since you'd be swimming against the current. So, Tung and his coworkers made a replica of it in the lab, a 4-centimeter-long, shallow pipe that researchers used to control the flow of a thick fluid that was meant to mimic natural mucus. Sperm have an innate tendency to move upstream, whether they are isolated or in a group.

In the experiment, however, sperm clusters did a better job of swimming upstream into the mucus flow than solitary sperm. Even though some sperm moved faster than others, the progress of sperm loners was slowed by the fact that they couldn't move upstream as quickly as sperm clusters.

Even in the presence of a torrent of mucus, the clusters maintained their path. Individual sperm were lost when researchers increased the flow rate in their equipment. Clusters of sperm had a significantly lower chance of being carried away by currents.

Despite the fact that the sperm used in the study was bovine, Tung believes that the benefits of clustering should apply to human sperm as well. Both species' sperm are around the same size.

Usually, many sperm swimmers will battle over a single ovum. Human and bovine sperm both begin their journey to the uterus in the vagina, unlike pigs and other species whose semen is deposited straight into the uterus. Tung argues that difficulties with sperm motility may be uncovered by studying them in fluids that mimic the moving mucus found in reproductive systems.

One possible benefit of this research is improved diagnostics, which could lead to a deeper understanding of the causes of infertility in humans. Fertility researcher Christopher Barratt of the University of Dundee in Scotland, who was not involved with the study, says that simulating natural conditions for sperm in the lab could one day help couples who are having problems conceiving.

Conclusion

According to Christopher Barratt:

“„How a sperm cell responds to its surroundings and how that may change its behavior is a very important subject. This type of technology could be used, or adapted, to select better quality sperm, for people in need of fertility assistance. That would be a very big deal.- Fertility researcher Christopher Barratt of the University of Dundee in Scotland

Jump to

Camilo Wood

Author

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Dexter Cooke

Reviewer

Dexter Cooke is an economist, marketing strategist, and orthopedic surgeon with over 20 years of experience crafting compelling narratives that resonate worldwide.

He holds a Journalism degree from Columbia University, an Economics background from Yale University, and a medical degree with a postdoctoral fellowship in orthopedic medicine from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Dexter’s insights into media, economics, and marketing shine through his prolific contributions to respected publications and advisory roles for influential organizations.

As an orthopedic surgeon specializing in minimally invasive knee replacement surgery and laparoscopic procedures, Dexter prioritizes patient care above all.

Outside his professional pursuits, Dexter enjoys collecting vintage watches, studying ancient civilizations, learning about astronomy, and participating in charity runs.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles