George Washington - Biography Of America's First President

Beyond cherry trees and wigs, delve into the real George Washington. Explore his military genius, political triumphs, and complex legacy in this comprehensive biography.

Author:Emily SanchezReviewer:Elisa MuellerJan 02, 2024335 Shares66.9K Views

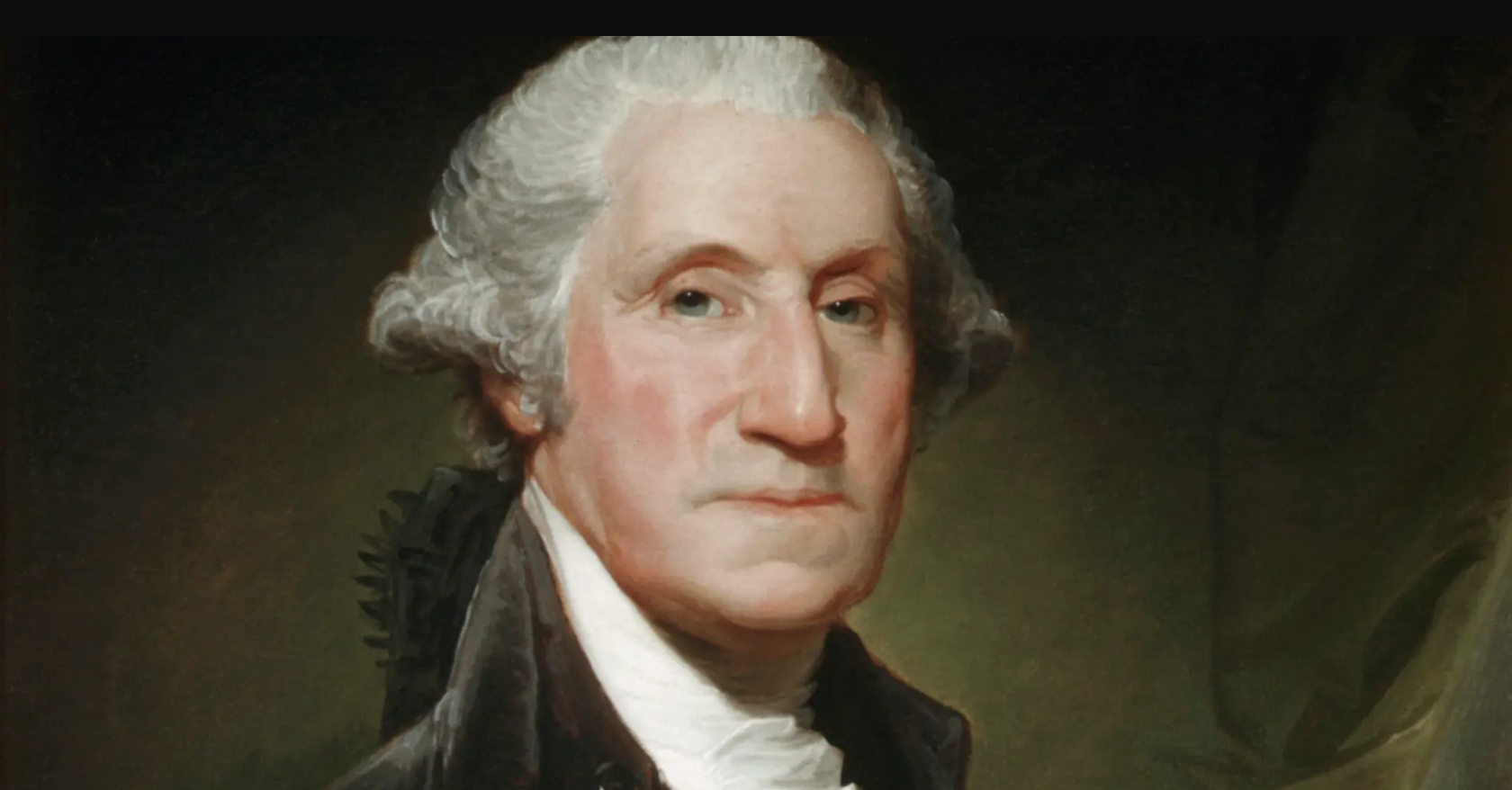

Forget the cherry tree and the powdered wig. The real George Washingtonis far more captivating, a figure etched not just in marble but in the very fabric of American history. He was a man of contradictions, a Revolutionary General, a cautious strategist who dared to defy an empire, and a reluctant president who shaped a fledgling nation.

His story is one of unwavering determination, forged in the wilderness of Virginia and tested on the battlefields of the American Revolution. It's a tale of political acumen, as he navigated the treacherous waters of a new republic and laid the cornerstone for American democracy. And it's a journey of human complexities, where personal ambition intertwined with profound responsibility, leaving behind a legacy as multifaceted as the man himself.

The Early Years Of George Washington

When Was George Washington Born - Where Was George Washington Born

George Washington, born on February 22, 1732, at his family's estate on Pope's Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia, was the first child of Augustine Washington (1694-1743) and Mary Ball Washington (1708-89). His childhood was primarily spent at Ferry Farm, a plantation near Fredericksburg, Virginia. Following the death of his father at the age of 11, it is likely that Washington played a role in assisting his mother in managing the plantation.

While specific details about Washington's early education are limited, it is known that children from affluent families, like his own, were typically educated at home by private tutors or attended private schools. Washington is believed to have concluded his formal education around the age of 15.

During his teenage years, Washington, displaying a talent for mathematics, found success as a surveyor. His surveying ventures in the Virginia wilderness proved lucrative, enabling him to accumulate land holdings. In 1751, he embarked on his sole journey outside of America, traveling to Barbados with his older half-brother Lawrence Washington (1718-52), who was seeking relief from tuberculosis in the warm climate.

George contracted smallpox during the trip but survived, albeit with permanent facial scars. In 1752, Lawrence, Washington's mentor educated in England, passed away. Washington eventually inherited Lawrence's estate, Mount Vernon, situated on the Potomac River near Alexandria, Virginia.

How Tall Was George Washington

Determining George Washington's exact height is a bit of a historical mystery. While there are various estimations and claims, no definitive measurement exists. Here's what we know:

Estimates

- 6 ft 0 in (1.83 m) -This is the most commonly cited height, based on various accounts and comparisons to furniture and other objects.

- 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m) -Some sources suggest this slightly shorter stature, based on European clothing measurements of the time.

- 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) -This taller estimate comes from anecdotal accounts and comparisons to portraits and statues.

Officer And Gentleman Farmer

What Did George Washington Do

In December 1752, Washington, lacking any prior military background, was appointed as a commander of the Virginia militia. Engaging in the French and Indian War, he eventually assumed leadership of all of Virginia's militia forces.

By 1759, Washington had stepped down from his military position, returned to Mount Vernon, and secured a seat in the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he served until 1774. In January 1759, he entered matrimony with Martha Dandridge Custis (1731-1802), a prosperous widow with two children. Despite not having any biological children together, Washington became a dedicated stepfather to her offspring.

Over the subsequent years, Washington transformed Mount Vernon from a 2,000-acre property into an expansive 8,000-acre estate encompassing five farms. Cultivating a variety of crops such as wheat and corn, he also engaged in mule breeding and maintained flourishing fruit orchards and a successful fishery. Washington's profound interest in farming led him to consistently experiment with new crops and innovative land conservation methods.

George Washington In The American Revolution

Washington demonstrated greater prowess as a general than as a military strategist during the American Revolution. His strength lay not in tactical brilliance on the battlefield but in his skill at maintaining cohesion within the struggling colonial army.

Faced with poorly trained troops lacking essential provisions such as food, ammunition, and even shoes in winter, Washington's leadership provided direction and motivation. His notable leadership during the harsh winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge showcased his ability to inspire his men to persevere.

Having personally witnessed the impact of escalating taxes imposed by the British on American colonists in the late 1760s, Washington came to the conviction that declaring independence from England was in the best interests of the colonists. Serving as a delegate to the First Continental Congressin 1774 in Philadelphia, Washington was appointed commander in chief of the Continental Army when the Second Continental Congress convened a year later, coinciding with the earnest onset of the American Revolution.

Throughout the challenging eight-year conflict, the colonial forces secured few victories but consistently held their ground against the British. In October 1781, with support from the French, who allied with the colonists against the British, the Continental forces successfully captured British troops led by General Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) in the Battle of Yorktown. This pivotal action effectively concluded the Revolutionary War, and Washington was hailed as a national hero.

The First President Of The United States

When Did George Washington Became President

In 1783, following the signing of the Treaty of Paris between Great Britain and the U.S., Washington, feeling that he had fulfilled his duty, relinquished command of the army and returned to Mount Vernon, intending to resume his life as a gentleman farmer and family man. However, in 1787, he was called upon to participate in the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and lead the committee tasked with drafting the new constitution. His remarkable leadership during this time convinced the delegates that he was the most qualified individual to become the nation's inaugural president.

How Old Was George Washington When He Became President

Initially hesitant, Washington desired to return to a peaceful life at home and delegate the governance of the new nation to others. However, overwhelming public support eventually persuaded him to accept the role.

The first presidential election took place on January 7, 1789, and Washington emerged as the clear winner. John Adams (1735-1826), who garnered the second-largest number of votes, became the nation's first vice president. The 57-year-old Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, in New York City.

Since Washington, D.C., the future capital of America, had not yet been constructed, he resided in New York and later Philadelphia. During his presidency, he signed a bill establishing a future permanent U.S. capital along the Potomac River, a city later named Washington, D.C., in his honor.

George Washington's Achievements

Upon assuming office, Washington faced the challenge of leading a small nation comprising 11 states and approximately 4 million people, with no established precedent for presidential conduct in domestic or foreign affairs.

Mindful that his actions would shape expectations for future presidents, Washington diligently worked to exemplify fairness, prudence, and integrity. In foreign affairs, he advocated for amicable relations with other nations while maintaining a stance of neutrality in international conflicts.

On the domestic front, he nominated the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, John Jay (1745-1829), endorsed the establishment of the inaugural national bank, the Bank of the United States, and established his presidential cabinet.

His notable cabinet members included Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), who held opposing views on the role of the federal government.

While Hamilton supported a robust central government as part of the Federalist Party, Jefferson favored stronger states' rights within the Democratic-Republican Party, precursor to the Democratic Party. Washington recognized the importance of diverse perspectives for the well-being of the new government but expressed concern about the emerging partisanship.

Washington's presidency marked several significant firsts, including the signing of the first United States copyright law to protect authors' rights and the issuance of the first Thanksgiving proclamation designating November 26 as a national day of gratitude for the end of the war for American independence and the successful ratification of the Constitution.

During his term, Congress enacted the first federal revenue law, imposing a tax on distilled spirits. In response to the 1794 "Whiskey Rebellion" in Western Pennsylvania, Washington deployed over 12,000 militiamen, demonstrating the authority of the national government.

Under Washington's guidance, the states ratified the Bill of Rights, and five new states joined the union: North Carolina (1789), Rhode Island (1790), Vermont (1791), Kentucky (1792), and Tennessee (1796).

In his second term, Washington issued the proclamation of neutrality to avoid involvement in the 1793 war between Great Britain and France. The signing of Jay's Treaty in 1795 averted war with Great Britain but stirred controversy domestically, particularly with opposition from Jefferson and Madison.

Washington's administration also signed influential international treaties, including Pinckney's Treaty of 1795, establishing friendly relations with Spain, and the Treaty of Tripoli in 1796, providing American ships access to Mediterranean shipping lanes in exchange for an annual tribute to the Pasha of Tripoli.

George Washington's Retirement, Return To Mount Vernon, And Passing

After two presidential terms and a decision to decline a third term in 1796, George Washington retired from political life. In his farewell address, he advised the new nation to uphold the highest domestic standards and minimize involvement with foreign powers. This address is still annually recited in the U.S. Senate each February to commemorate Washington's birthday.

When Did George Washington Die - How Did George Washington Die

Returning to Mount Vernon, Washington focused on restoring the plantation's productivity to its pre-presidential levels. Although over four decades of public service had taken a toll on him, he remained a commanding figure. In December 1799, he contracted a cold while inspecting his properties in the rain. The cold developed into a throat infection, leading to Washington's passing on the night of December 14, 1799, at the age of 67.

Where Is George Washington Buried

He was interred at Mount Vernon, which attained national historic landmark status in 1960.

Washington left an enduring legacy as the "Father of His Country." His likeness graces the U.S. dollar bill and quarter, and numerous U.S. schools, towns, counties, the state of Washington, and the nation's capital city are named in his honor.

Frequently Asked Questions - George Washington

Was George Washington A Slave Owner?

Indeed, George Washington was a slave owner. Born into a Virginia planter family, he inherited 10 enslaved individuals after his father's death in 1743. In 1761, Washington obtained a farmhouse known as Mount Vernon, later expanding it into a five-farm estate.

The number of enslaved individuals on the estate grew from 49 in 1760 to over 300 by 1799. Eventually, Washington emancipated the 123 people he owned, stipulating in his will that they be freed "upon the decease of my wife".

Did George Washington Have Wooden Teeth?

Contrary to popular belief, George Washington did not have wooden teeth. This is a persistent myth that can be traced back to the 19th century. In reality, his dentures were made from a variety of materials, including Hippopotamus ivory, Human teeth, Animal teeth and Metal alloys.

Was It True That George Washington Chopped Down His Father's Cherry Tree?

For years, a narrative circulated about the first U.S. president involving a hatchet, a cherry tree, and a young Washington renowned for "cannot tell a lie." The legend sought to portray George Washington as a paragon of honesty, virtue, and piety.

However, the tale is not based on reality. It was crafted by a 19th-century bookseller named Mason Locke Weems, who aimed to provide a moral exemplar for American readers. This legend, like several others about Washington, is a fabrication.

Conclusion

George Washington's life wasn't a neatly packaged narrative, but a tapestry woven with threads of brilliance and folly, courage and contradiction. He was a man of the wilderness who led a nation, a revolutionary general who grappled with the complexities of liberty, a cautious strategist who dared to dream of a new republic.

His legacy transcends the granite monument on the Potomac. It lives in the foundations of American democracy, the checks and balances that ensure liberty for all. It echoes in the echoes of "No taxation without representation!" and the quiet dignity of stepping down from power. It whispers in the rustle of flags carried by soldiers inspired by his unwavering resolve.

George Washington was not flawless, but he was exceptional. He dared to build a nation where none had existed before, and in doing so, he etched his name not just in stone, but in the very soul of America.

Jump to

The Early Years Of George Washington

Officer And Gentleman Farmer

George Washington In The American Revolution

The First President Of The United States

George Washington's Achievements

George Washington's Retirement, Return To Mount Vernon, And Passing

Frequently Asked Questions - George Washington

Conclusion

Emily Sanchez

Author

Emily Sanchez, a Fashion Journalist who graduated from New York University, brings over a decade of experience to her writing. Her articles delve into fashion trends, celebrity culture, and the fascinating world of numerology.

Emily's unique perspective and deep industry knowledge make her a trusted voice in fashion journalism.

Outside of her work, she enjoys photography, attending live music events, and practicing yoga for relaxation.

Elisa Mueller

Reviewer

Elisa Mueller, a Kansas City native, grew up surrounded by the wonders of books and movies, inspired by her parents' passion for education and film.

She earned bachelor's degrees in English and Journalism from the University of Kansas before moving to New York City, where she spent a decade at Entertainment Weekly, visiting film sets worldwide.

With over 8 years in the entertainment industry, Elisa is a seasoned journalist and media analyst, holding a degree in Journalism from NYU. Her insightful critiques have been featured in prestigious publications, cementing her reputation for accuracy and depth.

Outside of work, she enjoys attending film festivals, painting, writing fiction, and studying numerology.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles