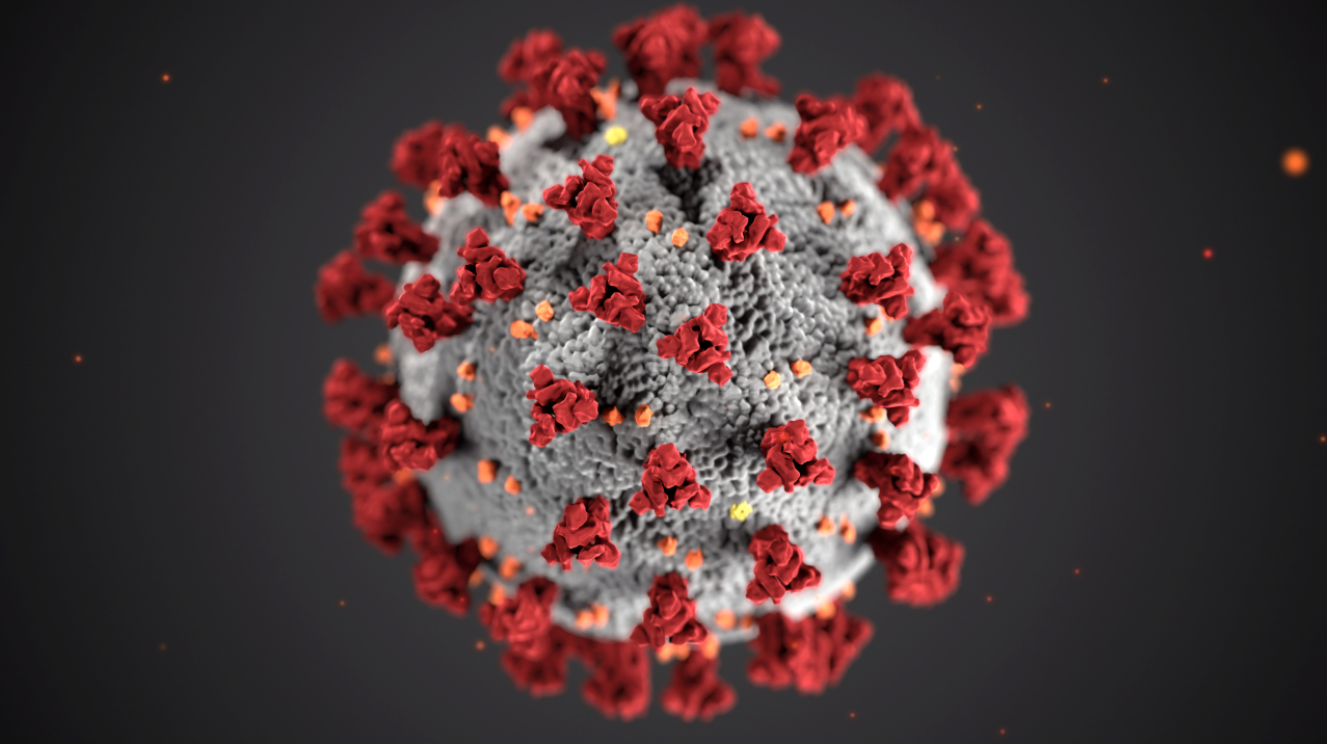

Sneaky Omicron Mutation Could Lead To An Outbreak Of COVID-19 This Fall

Winter and fall have not been kind to us in recent years, but a sneaky omicron mutation could lead to an outbreak of COVID-19 this fall. In 2020, COVID-19 instances started to increase in October. And last year, we were, in a sense, in the quiet before the storm as the omicron variety started on its path to global dominance at the end of November, while the delta-driven case counts were steadily declining. What will happen as omicron continues to develop and many people stop using masks in our third pandemic winter?

Author:Karan EmeryReviewer:Daniel JamesOct 18, 2022145.4K Shares2.1M Views

Winter and fall have not been kind to us in recent years, but a sneaky omicron mutation could lead to an outbreak of COVID-19 this fall.

In 2020, COVID-19 instances started to increase in October. And last year, we were, in a sense, in the quiet before the storm as the omicron variety started on its path to global dominance at the end of November, while the delta-driven case counts were steadily declining. What will happen as omicron continues to develop and many people stop using masks in our third pandemic winter?

Time will only tell. But there are already some indicators that we might be in for yet another wave of illnesses, hospitalizations, and fatalities. One is that some European nations, like the United Kingdom, are seeing an increase in cases and hospitalizations.

Typically, what occurs abroad foretells what will take place in the US. Cases are still declining both nationally and in most states. As temperatures drop and more people assemble indoors, where the coronavirus is more prone to spread, researchers are concerned that this may not be the case for very long. For instance, coronavirus levels in wastewater have sharply increased in some Northeastern states, indicating an increase in transmission even if it hasn't yet been captured in official case counts.

This year's wild card further complicates things. Numerous omicron variants exist. How might they alter the impending course of the pandemic?

Answering that question is difficult. On the one hand, with additional medicines available and an omicron-specific booster, we're in a significantly different position than we were two years ago or even last year. But the coronavirus has a history of throwing us some unexpected curveballs. Winter is predicted to bring yet another wave, although it's unclear what it will look like or how high it will peak.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said during a webinar on October 4 in Los Angeles hosted by the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, "Although we can feel good that we are going in the right direction, we can't let our guard down."

The majority of people have been exposed to the virus, whether by immunization, an infection, or both of those less favorable routes. That implies that the virus's mug photo is present in our immune systems. As soon as the coronavirus enters our noses, throats, or lungs, our antibodies and T cells are programmed to go into high gear.

The bad news is that the omicron variety has acquired a few disguises over the past year in the form of mutations that assist the virus in evading our immune systems. Over the course of the summer, a version known as BA.5 overtook its relatives BA.2 and BA.2.12.1 to take over. Researchers are currently monitoring a new alphanumeric form of the omicron family.

Conclusion

As happened in 2021 with the delta and omicron variants, it is feasible for a brand-new unsettling variant to sporadically emerge and outcompete all of its relatives. "pi" would be the next name on the list.

Another, maybe more plausible, scenario is that during the coming months, a swarm of novel varieties will capture our attention rather than a single lineage that spreads over the globe. That's in part due to the competition between the virus and our immune systems.

Jump to

Karan Emery

Author

Karan Emery, an accomplished researcher and leader in health sciences, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals, brings over two decades of experience to the table. Holding a Ph.D. in Pharmaceutical Sciences from Stanford University, Karan's credentials underscore her authority in the field.

With a track record of groundbreaking research and numerous peer-reviewed publications in prestigious journals, Karan's expertise is widely recognized in the scientific community.

Her writing style is characterized by its clarity and meticulous attention to detail, making complex scientific concepts accessible to a broad audience. Apart from her professional endeavors, Karan enjoys cooking, learning about different cultures and languages, watching documentaries, and visiting historical landmarks.

Committed to advancing knowledge and improving health outcomes, Karan Emery continues to make significant contributions to the fields of health, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals.

Daniel James

Reviewer

Daniel James is a distinguished gerontologist, author, and professional coach known for his expertise in health and aging.

With degrees from Georgia Tech and UCLA, including a diploma in gerontology from the University of Boston, Daniel brings over 15 years of experience to his work.

His credentials also include a Professional Coaching Certification, enhancing his credibility in personal development and well-being.

In his free time, Daniel is an avid runner and tennis player, passionate about fitness, wellness, and staying active.

His commitment to improving lives through health education and coaching reflects his passion and dedication in both professional and personal endeavors.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles