Soil Carbon Sequestration - Conventional And Non-Conventional Techniques For Negative Emission Strategy

Soil carbon sequestration is increasing the amount of carbon stored as organic matter in soil, especially in agricultural and grazing regions.

Author:Camilo WoodReviewer:Dexter CookeOct 10, 2023271 Shares271.2K Views

Soil carbon sequestrationis increasing the amount of carbon stored as organic matter in the soil, especially in agricultural and grazing regions.

To 1 m deep, global soils contain about 1,500 Gt of organic carbon and 2,400 GtC to 2 m depth. Most farmland mineral soils have lost 30-50% of their carbon stocks in soil layers (0-30 cm) compared to their natural state.

Grassland soils may or may not have had comparable carbon losses, depending on how they are maintained. The soil and crop management strategies used in managed ecosystems influence the rate of carbon input and soil carbon loss.

Soil carbon stocks gravitate toward a new equilibrium state; hence, carbon increases attenuate after a few decades, becoming progressively minor over time.

Soil organic matter has a very narrow C:N stoichiometry in most mineral soils, ranging from 8 to 20.

Many farmland soils in North America, Europe, China, India, and Southeast Asia now lose a large quantity of additional N via gaseous losses and nitrate leaching.

What Is Carbon Sequestration?

Soil carbon sequestration removes CO2 from the atmosphere and stores it in the soil carbon pool.

Plants predominantly mediate this process via photosynthesis, with carbon stored in the form of soil organic carbon.

Soil carbon sequestration may also occur in dry and semi-arid regions due to the conversion of CO2 from air found in soil into inorganic forms such as secondary carbonates; however, the rate of inorganic carbon creation is very modest.

Conventional Conservation Practices For Soil Carbon Sequestration

Numerous field tests and comparative observations have shown the conservation measures that may lead to increased soil carbon reserves.

Several activities are categorized based on their primary mechanism of action in either enhancing carbon inputs to soils or decreasing carbon losses.

Improving Crop Rotations And Cover Cropping

Farmers may plant high-residue crops, seasonal cover crops/green manure, engage in continuous cropping (lower fallow frequency), and plant permanent or rotating perennial grasses to boost carbon inputs into soils.

Farmers leave their fields fallow in many arid regions every year to save soil moisture and maintain stable grain harvests.

In such systems, intensifying and diversifying crop rotations may enhance average annual carbon inputs, resulting in greater soil carbon stores than in high fallow frequency systems.

Adding 2–3 years of perennial hay/forage crops to row crop rotations in wetter areas enhances carbon inputs from fine roots and raises soil organic carbon reserves.

Adding Manure And Compost In The Soil

The soil carbon sequestration depends on increasing the quantity of carbon stored as organic matter in the soil. 45% of the world's soils are used for agriculture. Where anaerobic conditions inhibit plant breakdown, organic soils develop.

Most agricultural soils (both mineral and organic) contain less carbon than natural ecosystems. Most farmland soils have lost 30–50% of their topsoil carbon stores.

Grazing-managed grassland soils may or may not have experienced comparable carbon losses. The rate of detrital carbon inputs in native ecosystems depends on the type (annual vs. perennial, woody vs. herbaceous) and the productivity of the vegetation.

The pace of decomposition is determined by several elements, including soil temperature and moisture. Typically ranging between 8 and 20, soil organic matter's C:N ratio is relatively narrow.

Numerous farmland soils in North America, Europe, China, India, and Southeast Asia now lose a substantial quantity of nitrogen (from fertilizer, manure, and N-fixation) via gaseous losses and leached nitrate.

Improving Tillage Practice

Tillage is the primary form of soil disturbance in annual croplands and is used by farmers to manage crop leftovers and prepare a seedbed for crops.

Tillage technology and agronomic practice advancements have enabled farmers to minimize tillage frequency and intensity.

Some farmers have abandoned tillage, a technique known as "no-till." No-till systems offer a 66% lower Global Warming Potential and a 71% lower greenhouse gas intensity (greenhouse gaseous emissions per unit of produce) than traditionally tilled systems.

One-time deep inversion tillage in humid and subhumid croplands may be particularly successful in promoting a considerable rise in soil carbon stores.

This method requires burying carbon-rich surface horizons to 60-80 cm depth and transferring low-carbon subsurface material to the surface.

"Traditional" carbon sequestering strategies, such as no-till and high residue crops, have the potential to develop fresh carbon stocks in surface soil layers quickly.

Converting Carbon To Perennial Grasses And Legumes

We see an increase in carbon inputs and a decrease in soil disturbance when croplands are converted to perennial vegetation (grasses, trees). Set-aside lands are those that have been removed from arable production.

The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) in the United States pays farmers to retire marginal and highly erodible croplands, with a peak cumulative enrolment of little over 35 million acres.

According to the Environment Protection Agency's National Greenhouse Gas Inventory report, Conservation Reserve Program land significantly contributes to agricultural soil carbon sinks in the United States.

Initial rates of soil organic carbon accumulation may be significant. Long-term field investigations have shown that accumulations can last for decades, nearing native soil organic carbon stock levels.

Carbon Sequestration Through Rewetting Organic Soils

Organic soils are peat and muck-derived soils whose total bulk is mainly composed of organic materials.

Organic soils do not experience saturation in the same manner as mineral soils do. Organic soils are often drained, limed, and fertilized when used for agriculture.

Although they may be quite productive for yearly cropping, conversion to agriculture results in significant CO2 emissions.

Carbon Sequestration Through Improved Grazing Land Management

Non-forested grazing areas in the United States are generally classified into pastures and rangelands.

Because pastures are often made up of non-indigenous and non-native plants, they provide more intense and diversified management alternatives (e.g., fertilization, irrigation, plant species introduction, and grazing management).

Rangelands are grasslands dominated by native plants often found in arid areas. Increasing soil organic carbon primarily depends on increasing carbon inputs from plant roots and residues.

There is interest in intensive grazing strategies that use high animal stocking rates for short periods to improve productivity and soil quality on grazing pastures.

Such management approaches are labeled with various labels such as rotation grazing, mob grazing, or adaptable multi-paddock grazing.

Some research implies that adaptable multi-paddock grazing systems significantly affect productivity, soil physical characteristics, and soil carbon reserves.

Others have argued that adaptable multi-paddock/rotational grazing systems are inferior to well-managed continuous grazing systems.

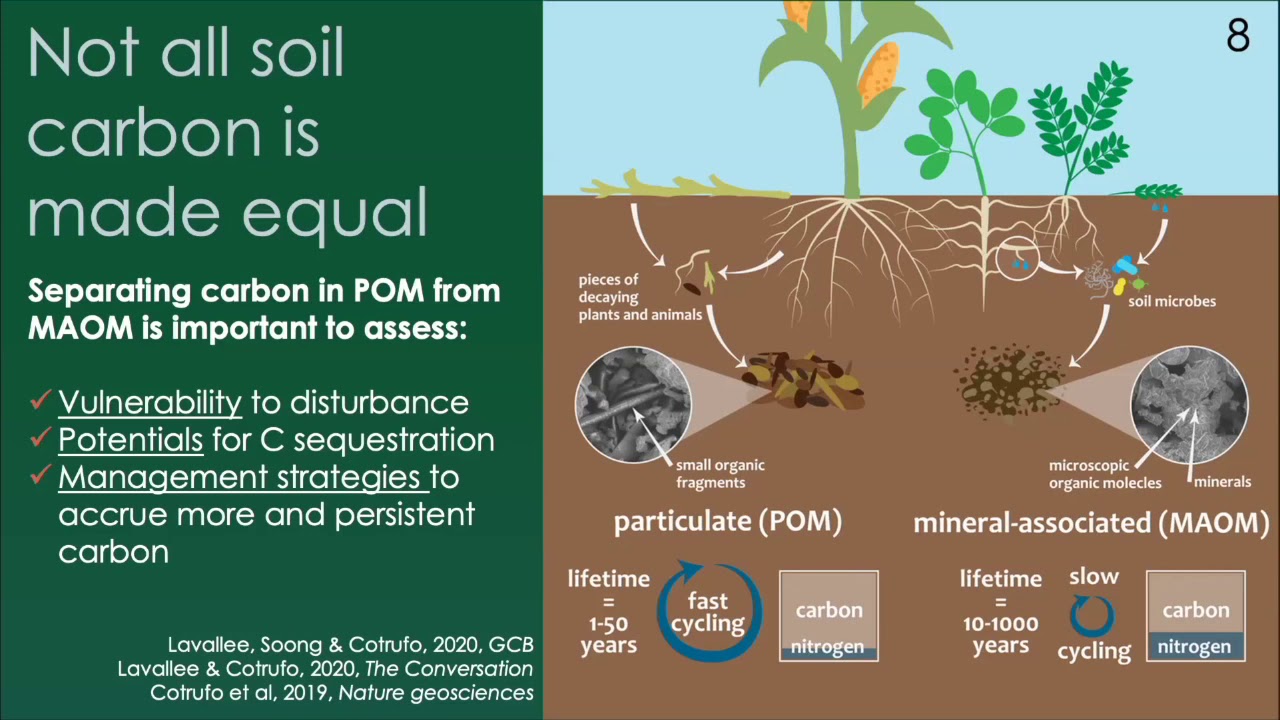

Carbon sequestration in soils | Francesca Cotrufo | Global Carbon Management Workshop

Non-conventional Management Practice For Soil Carbon Sequestration

"Non-traditional" management approaches have great potential for creating negative emissions, but more study is needed to develop the requisite technologies.

Among the technologies under consideration are biochar application to farmland soils, deployment of perennial grain crops, and adoption of annual crops designed to develop deeper and more extensive root systems for increased carbon inputs.

Addition Of Biochar

Biochar is a carbon-rich solid from biomass by pyrolysis, a thermochemical conversion process. Many fire-prone environments, such as grasslands, savannas, and forests, include biochar in their soils.

When biochar is put into the soil, most of the mass (80-95%) is resistant to microbial degradation. Biochar is a carbon stock that, once applied to soil, has a long shelf life.

Biochar additions may also interact with the local organic matter already present in soils, accelerating or slowing decomposition.

The effects of biochar inputs on plant production might vary greatly depending on biochar properties and soil/plant variables.

The principal influence of biochar amendment on greenhouse gas balance is connected with the biochar's long-term storage when applied to the soil.

There is a growing agreement that biochar treatments assist in lowering N2O emissions on average.

The reduction depends on the biochar life cycle, biomass feedstock production, and harvesting emissions.

Perennial Grain Crops DevelopDevelopment

Perennial crops would eliminate the requirement for tillage and the detrimental consequences on soil organic carbon stocks and soil erosion.

More extensive and deeper root systems may help minimize nitrate leaching losses to rivers and N2O emissions to the atmosphere.

Because carbon inputs to soil are substantially higher than annual crops, soil organic carbon reserves will be much higher.

Perennial grain yields are minimal, making economic sustainability uncertain if scaled out. Intermediate wheatgrass yields are generally 1,000 kg/ha, 5-10 times lower than annual wheat yields in the same sites.

Other concerns include grain breaking, lodging, tiny seed size, and a lack of agronomics understanding.

Perennial grains promise to expand the range of ecosystem services given by agriculture. Still, more effort has to be made to develop cultivars with consistent regrowth and acceptable grain yields.

Opportunities for the successful first commercialization of perennial grain crops include the potential for mixed grain and forage production and the exploitation of marginal areas.

Development Of Deeper And Larger Root Systems In Crops

Future crops could have more significant carbon inputs to soil and deeper root distributions, increasing soil carbon storage.

In 2012, Kell laid out a rationale for the potential to direct plant breeding efforts toward developing varieties for our major grain crops with greater carbon allocationcarbon storage rates, native soil organic carbon stock levels to roots, and deeper root distribution.

Widespread adoption of annual crop phenotypes could yield soil carbon stock increases of 0.5 Gt CO2/ha/y on the current US cropland.

Estimates Of CO2 Sequestration And Removal In Soils

Global and US soil carbon sequestration potentials are estimated. Most projections are based on heavily aggregated land-use and climatic data.

Global estimations show that optimum conservation management methods might sequester 2–5 Gt CO2 per year.

Agricultural areas may use various management strategies to extract CO2 and convert it to soil organic matter.

According to estimates, widespread BMPs might save 4–5 Gt CO2 annually.

These carbon storage rates might last 2–3 decades before declining when soil carbon levels reach a new equilibrium.

Most estimates are based on highly aggregated data on the total area by land-use type, stratified into widely defined climatic categories, and applying per ha soil carbon sequestration rates.

Lower estimates involve less acreage (e.g., farmland exclusively) and fewer practices. Global estimates show optimum conservation management methods might save 2–5 Gt CO2 per year.

People Also Ask

What Is The Best Way To Sequester Carbon?

The best way to get rid of carbon is to put it back where it belongs, in places like forests, grasslands, and soil.

To meet the 1.5°C goals, we need to quickly improve the ability of natural carbon sinks to pull carbon out of the air.

This is also needed to stop the land from becoming a desert.

What Crops Sequester The Most Carbon?

Grasses had the highest carbon allocation to roots (Rc/Sc = 1.19 ± 0.08), followed by cereals (0.95 ± 0.03), legumes (0.86 ± 0.04), oil crops (0.85 ± 0.08), and fiber crops (0.50 ± 0.07).

Plant carbon stores were high in crops produced on carbon-rich clayey soils in humid tropical areas.

Does Grass Sequester More Carbon Than Trees?

According to University of Florida research, well-maintained lawns capture much less carbon than less-maintained natural environments.

Indeed, lawns with greater grass cover than tree canopy may begin to generate carbon.

Conclusion

There is a lot of evidence from science that agricultural soils will take in a lot of carbon over the next few decades.

There are many ways to store carbon; the best depends on the climate, soil, and land farm.

Based on existing technologies, a strong policy could be put in place immediately to start an international effort to increase the amount of carbon stored in the soil.

Many countries could move to implement negative emission strategies in the agricultural sector and improve the health and resilience of their soils at the same time.

This would help keep average global temperature increases to 2°C by boosting and encouraging global efforts.

Much of the infrastructure needed for a sound MRV system for soil carbon sequestration could be put together quickly and with only a tiny amount of money spent on research and development.

Camilo Wood

Author

Camilo Wood has over two decades of experience as a writer and journalist, specializing in finance and economics. With a degree in Economics and a background in financial research and analysis, Camilo brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to his writing.

Throughout his career, Camilo has contributed to numerous publications, covering a wide range of topics such as global economic trends, investment strategies, and market analysis. His articles are recognized for their insightful analysis and clear explanations, making complex financial concepts accessible to readers.

Camilo's experience includes working in roles related to financial reporting, analysis, and commentary, allowing him to provide readers with accurate and trustworthy information. His dedication to journalistic integrity and commitment to delivering high-quality content make him a trusted voice in the fields of finance and journalism.

Dexter Cooke

Reviewer

Dexter Cooke is an economist, marketing strategist, and orthopedic surgeon with over 20 years of experience crafting compelling narratives that resonate worldwide.

He holds a Journalism degree from Columbia University, an Economics background from Yale University, and a medical degree with a postdoctoral fellowship in orthopedic medicine from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Dexter’s insights into media, economics, and marketing shine through his prolific contributions to respected publications and advisory roles for influential organizations.

As an orthopedic surgeon specializing in minimally invasive knee replacement surgery and laparoscopic procedures, Dexter prioritizes patient care above all.

Outside his professional pursuits, Dexter enjoys collecting vintage watches, studying ancient civilizations, learning about astronomy, and participating in charity runs.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles