The Importance Of The Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is an Egyptian canal (Arabic:, Qan al-Suways, French: Le Canal de Suez). It is located to the west of the Sinai Peninsula. The canal is 163 kilometers long (101 miles) and 300 meters broad at its narrowest point (984 ft). It connects the Mediterranean Sea's Port Said (Br Sa'd) to the Red Sea's Suez (al-Suways).

Author:Paolo ReynaReviewer:James PierceOct 06, 202119.6K Shares364.6K Views

The Suez Canal is an Egyptian canal (Arabic:, Qan al-Suways, French: Le Canal de Suez). It is located to the west of the Sinai Peninsula. The canal is 163 kilometers long (101 miles) and 300 meters broad at its narrowest point (984 ft). It connects the Mediterranean Sea's Port Said (Br Sa'd) to the Red Sea's Suez (al-Suways). It was constructed by a French firm. The canal was constructed between 1859 and 1869. It is a sea-level waterway that connects the Mediterranean and Red seas and runs north-south across Egypt's Isthmus of Suez.

The canal connects Africa and Asia, and it is the shortest maritime route between Europe and the countries bordering the Indian and western Pacific oceans. It is one of the busiest shipping waterways on the planet. Between Port Said (Br Sad) in the north and Suez in the south, the canal stretches 193 kilometers (120 miles), with dredged approach channels north of Port Said, into the Mediterranean, and south of Suez. The canal does not take the shortest path through the isthmus, which is only 121 km (75 miles) (75 miles).

Instead, it utilizes multiple lakes: from north to south, Lake Manzala (Buḥayrat al-Manzilah), Lake Timsah (Buḥayrat al-Timsāḥ), and the Bitter Lakes—Great Bitter Lake (Al-Buḥayrah al-Murrah al-Kubrā) and Little Bitter Lake (Al-Buḥayrah al-Murrah al-Ṣughrā). Although there are enormous straight sections, the Suez Canal is an open cut with no locks, and there are eight major bends. The Nile River's low-lying delta lies to the west of the canal, while the Sinai Peninsula lies to the east, higher, mountainous, and desert. Suez, which had 3,000 to 4,000 inhabitants in 1859, was the sole significant community prior to the canal's completion (in 1869). With the probable exception of Al-Qanarah, the rest of the settlements along its banks have sprung up since then.

What Country Owns And Operates The Suez Canal?

Today, the Suez Canal is currently being operated by the Egyptian government. A quick history about the canal: The Suez Canal was completed in 1859 after a ten-year construction period by the Universal Suez Ship Canal Company. The first ship to travel through the canal did so on February 17, 1867, and for this occasion, Giuseppe Verdi composed the classic opera, Aida. There were just 486 transits in 1870, the canal's first full year of operation, or less than two per day. There were 21,250 in 1966, with an average of 58 per day, and net tonnage increased from 444,000 metric tons (437,000 long tons) in 1870 to almost 278,400,000 metric tons in 1966. (274,000,000 long tons).

The number of daily transits had dropped to an average of 50 by the mid-1980s, but the net yearly tonnage was still around 355,600,000 metric tons (350,000,000 long tons). In 2018, there were 18,174 transits, totaling approximately 1,139,630,000 metric tons (1,121,163,000 long tons). The canal was blocked after the 1967 Six-Day War and remained closed until June 5, 1975. Since 1974, a UN peacekeeping force has been stationed in the Sinai Peninsula to prevent further hostilities.

The original canal did not enable two-way travel, so ships had to stop in a passing bay to let ships in the opposite direction pass. The average transit time back then was 40 hours, but by 1939, it had dropped to 13 hours. In 1947, a convoy system was established, with one northbound and two southbound convoys every day. Despite convoying, transit duration increased to 15 hours in 1967, indicating the rapid growth in tanker traffic at the time. Since 1975, when the canal was widened, journey times have averaged from 11 to 16 hours. Ships are assessed for tonnage and cargo upon entering the canal at Port Said or Suez (passengers have been free since 1950) and are overseen by one or two pilots for actual canal transit, which is increasingly controlled by radar.

Southbound convoys moor in Port Said, Al-Ball, Lake Timsah, and Al-Kabrt, where bypasses allow northbound convoys to travel through without stopping. Because of aircraft competition, passenger traffic has decreased from an all-time high of 984,000 in 1945 to minimal levels today. The movement of Australasian trade from Europe to Japan and East Asia resulted in a further drop in canal traffic. However, some oil flow has persisted, primarily to India, from refineries in Russia, southern Europe, and Algeria, and the shipment of dry goods such as grain, ores, and metals has grown. Container and roll-on/roll-off (ro-ro) traffic through the canal has increased in recent years, primarily bound for the Red Sea and Persian Gulf's congested ports. Crude petroleum and petroleum products, coal, ores and metals, and fabricated metals, as well as wood, oilseeds and oilseed cake, and cereals, are the main northbound cargoes. Cement, fertilizers, manufactured metals, grains, and empty oil tankers make up the southbound trade.

Each year, around 15,000 ships sail through the canal, accounting for about 14% of global commerce. The canal might take up to 16 hours for each ship to cross. A center section of the canal was extended in 2015 to allow bigger ships to pass through and move faster. The canal made it feasible to carry commodities across the globe quickly and easily. The canal also made it possible for Europeans to go to East Africa, which was quickly conquered by European powers.

The Suez Canal's success inspired the French to attempt to construct the Panama Canal. They did not, however, complete it. Later, the Panama Canal was completed.

Where Is It And Why Is It Important?

The canal allows ships and boats to transit from Europe to Asia without passing through Africa. It was constructed to connect Egypt and the Indian Ocean. The Suez Canal is a man-made waterway in Egypt that runs north-south through the Suez Isthmus. The Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea, making it the quickest sea route from Europe to Asia. It has become one of the most heavily utilized maritime lanes on the planet since its completion in 1869.

4 Facts About The Suez Canal

Physiography & Geology Of The Canal

The Isthmus of Suez, the only land bridge connecting the continents of Africa and Asia, is geologically young. Both continents were once part of a single large continental mass, but during the Paleogene and Neogene periods (66 to 2.6 million years ago), the Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba developed great fault structures, resulting in the opening and subsequent drowning of the Red Sea trough as far as the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba. There was a significant sea-level fluctuation in the following Quaternary Period (about the last 2.6 million years), eventually leading to the creation of a low-lying isthmus that spread northward to a low-lying open coastal plain. The Nile delta once extended further east due to periods of abundant rainfall during the Pleistocene Epoch (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago), and two river arms, or distributaries, once crossed the northern isthmus, one branch reaching the Mediterranean Sea at the narrowest point of the isthmus and the other entering the sea 14.5 kilometers (9 miles) east of present-day Port Said.

The Isthmus of Suez is not uniform in terms of topography. Lake Manzala, Lake Timsah, and the Bitter Lakes are three shallow water-filled depressions; despite being divided into Great and Little Lakes, the Bitter Lakes create one continuous sheet of water. In the south of the isthmus, a number of more resistant bands of limestone and gypsum protrude, and a small valley running from Lake Timsah southwestward toward the middle Nile delta and Cairo is another notable feature. Marine sediments, coarser sands, and gravels deposited during early periods of heavy rainfall, Nile alluvium (particularly to the north), and windblown sands make up the isthmus.

History Of The Canal

When first completed in 1869, the canal consisted of a channel barely 8 meters (26 feet) deep, 22 meters (72 feet) broad at the bottom, and 61 to 91 meters (200 to 300 feet) wide at the top. To allow ships to pass each other, passing bays were built every 8 to 10 km (5 to 6 miles) (5 to 6 miles). During construction, 74 million cubic meters (97 million cubic yards) of sediments were excavated and dredged. The narrowness and tortuousness of the canal resulted in around 3,000 ship groundings between 1870 and 1884. Major renovations began in 1876, and by the 1960s, the canal had a minimum width of 55 meters (179 feet) at a depth of 10 meters (33 feet) along its banks and a channel depth of 12 meters (40 feet) at low tide, thanks to consecutive widenings and deepenings.

Passing bays were also greatly enlarged and new bays were built during that time period, bypasses were built in the Bitter Lakes and at Al-Ball, stone or cement cladding and steel piling for bank protection were almost entirely completed in areas particularly prone to erosion, tanker anchorages were deepened in Lake Timsah, and new berths were dug at Port Said to facilitate the grouping of ships in congested areas. The Arab-Israeli conflict of June 1967, during which the canal was shut, overtook plans for additional enlargement that had been established in 1964. The canal was shut down until June 1975, when it was reopened and upgrades were started. In 2015, the Egyptian government completed a roughly $8.5 billion project to improve the canal and greatly expand its capacity; the canal's initial length of 164 km was increased by almost 29 km (18 miles) (102 miles).

The Container Ship That Got Stuck In The Canal

What Really Happened at the Suez Canal?

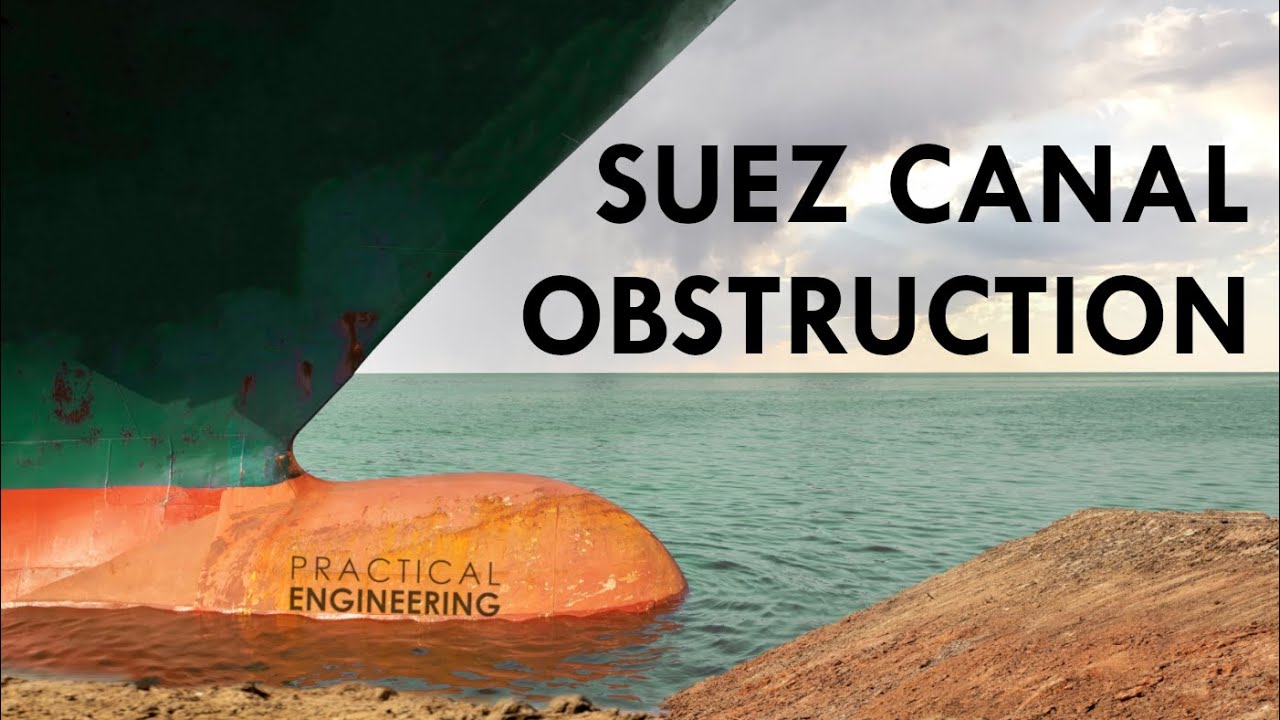

On March 23, 2021, a massive container ship, Ever Given, ran aground in the Suez Canal. The wedged vessel obstructed the entire channel, blocking one of the most important trade routes of the world for nearly a week. The cause and details of this event are still under investigation, but there’s a lot of speculation online as to the real cause of this event. But let’s dive first into some facts that ships have to know to successfully navigate through the canal.

The canal is a relatively straightforward structure: essentially a trapezoidal channel cut through the sand of the low-lying Suez Isthmus and taking advantage of the existing Great Bitter Lake at the center. Unlike the Panama Canal which uses locks to raise vessels up for transit, the Suez Canal is entirely at sea level with no gates or locks. Minor differences in level between the Mediterranean and Red Seas create gentle currents in the canal, but they’re not strong enough to trouble ships. In 2016, an expansion to the canal opened, essentially doubling its capacity.

The project involved a second shipping lane to part of the canal and deepening and widening some of the choke points so larger ships could pass through. It’s now about 200 meters (700 feet) wide and about 24 meters (80 feet) deep. All ships that pass through the canal are required to have a Canal authority pilot to help navigate each step. These pilots aren’t fully responsible for the safety of the ship during transit, but they have special knowledge about the processes, procedures, and challenges required to navigate these massive vessels through the canal. It’s tricky, and ships have been stuck in the canal before, including a 3-day blockage in 2004.

So, each ships’ Master (sometimes called the Captain) and the canal authority pilot work together to maneuver the ship through. It takes about half a day to get from one end to the other, and on average, about 50 ships make their way through the canal each day. Navigating the Suez Canal is a careful dance since some parts of the channel only have a single shipping lane with no room to pass. That’s why ships are required to go through in convoys. Early each morning, the convoys line up to enter the canal.

The southbound group begins their journey from about 3 am to 8 am at Port Said, following the western channel. At around the same time, the northbound enters the canal at Suez. on a normal day, everything is carefully timed so that the two convoys can pass each other in the Great Bitter Lake and the dual lane section of the canal without any stopping or interruptions. Unfortunately, March 24rd was not a normal day. One of the ships in the northbound convoy, Ever Given, had barely entered the canal when it veered into the eastern bank, smashing its bow to the sandy embankment and wedging the massive vessel diagonally across the channel’s entire width. Amazingly, there was not a single injury and the cargo was completely unharmed.

Now, here’s where the different speculations come in about the true cause of the incident. But let’s talk about some information about the ship.

Leased and operated by international shipping company Evergreen, the Ever Given is one of the eleven Golden Class container ships. These ships are truly massive. In fact, the Ever given will never get a chance to go through the Panama Canal because it’s too long for the locks at 400 meters (or over 1,300 feet long). If you remember the lesson on buoyancy, you know that a ship displaces its own weight in water. That means for every pound of steel and cargo aboard, a pound of water below the ship has to get out of the way.

For the Ever Given, that is hundreds of thousands of liquid being pushed to either side of the ship as it cuts through the water. On the open sea, that’s not a problem. The displacement forms a wake, but the water otherwise doesn’t have trouble finding a place to go. In a shallow canal though, things are a little different. In a shallow canal, all the water displaced by a ship has to essentially squish through the small areas along the side and the bottom of the vessel.

The smaller the area, the faster the water has to move out to get of the way. When traveling in a shallow area, the squished and sped-up flow below the hull creates a suction force pulling the ship further into the water, a phenomenon known as “squatting”. One massive ship even used the effect by speeding up as it went below the Great Belt bridge in Denmark to create some extra margin above the deck. But the same effect can happen on the side of a ship well. If a vessel gets too close to the bak of a shallow canal, the water it displaces on that side essentially has nowhere to go. It has to pick up speed as it squishes through the narrow gap, lowering the pressure, thus pulling the ship toward the bank.

Different social media were littered with a lot of amusing memes about a topic that everyone seemed to understand: A boat was stuck in a canal. It was in the way of other boats to get through. Simple as that. So, why did it take so long to dislodge? Humanity has a long and storied history of driving stuff to the ground so it will stay in place. It’s pretty intuitive how this works. The pullout force is resisted by the friction between the soil and the anchor. The ability to resist pullout is the function of the pressure against the soil and the surface area of the anchor. And when your anchor is a ship the size of a skyscraper, you have both of those in abundance. It’s really no wonder that salvage crews struggled to get the Ever Given unstuck. But, there is another geotechnical phenomenon that has not been yet proven but can be considered.

Memes About The Stuck Container Ship In The Canal

Paolo Reyna

Author

James Pierce

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles