A New Study Questions The Value Of Colonoscopy Screening

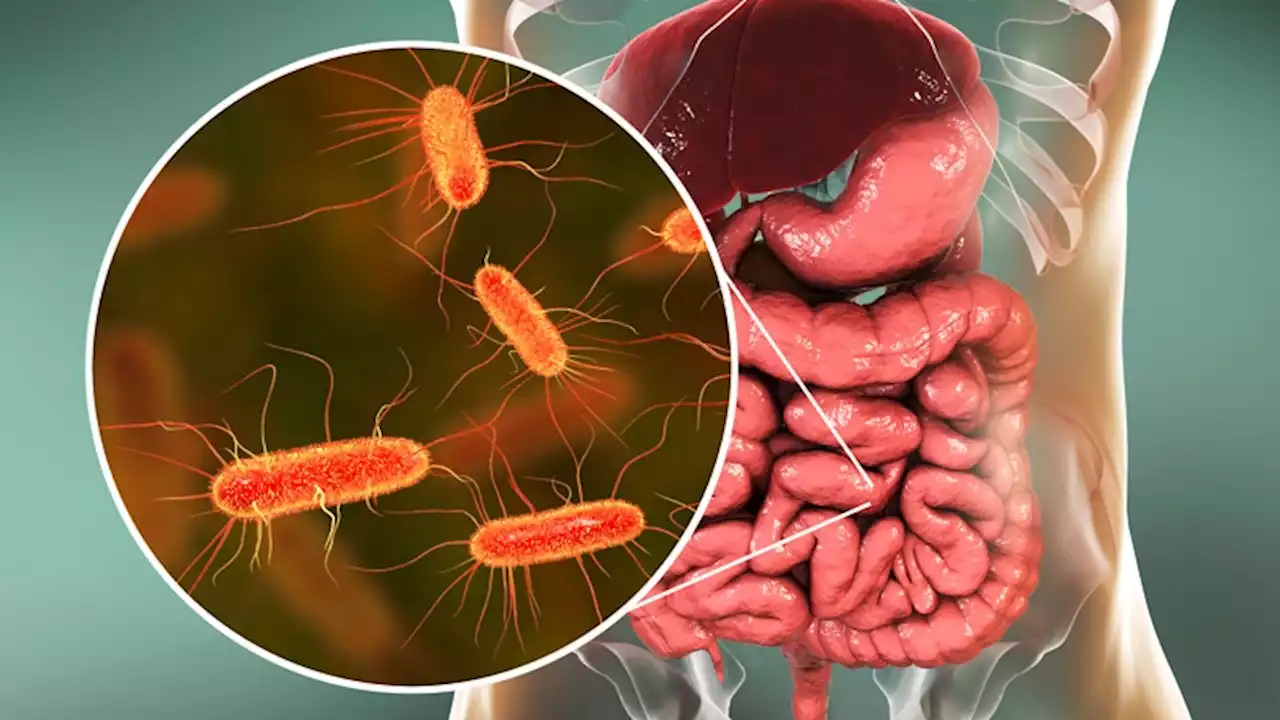

The key outcome of the experiment was the no value of colonoscopy screening in lowering cancer mortality over a 10-year period, which sparked a media frenzy. This finding contradicts the widely held idea that universal participation in this screening would effectively eradicate the vast majority of cases of colorectal cancer.

Author:Karan EmeryReviewer:Daniel JamesOct 23, 202254.3K Shares733.9K Views

The preliminary findings from major research evaluating the impact of inviting individuals to colonoscopy screening were published in the New England Journal of Medicine on Sunday. STAT's article about the report sparked a lot of interest and discussion in the medical community, as well as a lot of heated debate about how important the trial's results were and how the media covered the story.

The key outcome of the experiment was the no value of colonoscopy screeningin lowering cancer mortality over a 10-year period, which sparked a media frenzy. This finding contradicts the widely held idea that universal participation in this screening would effectively eradicate the vast majority of cases of colorectal cancer.

Despite the controversy, there was widespread agreement among specialists on the study and on colonoscopy screening in general. Even if the research found that invitations to colonoscopy were not very compelling, the essential fact remains: colonoscopy screening may reduce colorectal cancer and cancer-related mortality.

This research does not contradict the large body of literature that supports colonoscopy. The study added to the evidence that colonoscopy is a good way to prevent cancer, and experts all agreed that colonoscopy screening is a good idea.

The First Colonoscopy Randomized Study

The NordICC (Northern-European Initiative on Colon Cancer) research comprised 84,000 men and women aged 55 to 64 from Poland, Norway, and Sweden. None of them had ever undergone a colonoscopy. Between June 2009 and June 2014, people were given the chance to take part in a screening colonoscopy or be followed for the duration of the study without being tested.

In the ten years after enrolment, the group that was asked to get colonoscopies had an 18% lower risk of colorectal cancer than the group that was not. Overall, the screening group experienced a small decrease in their risk of dying from colorectal cancer, but the difference was not statistically significant, suggesting that it may just be due to chance.

Prior to the NordiCC study, the advantages of colonoscopies were determined by observational studies that compared the frequency of colorectal cancer diagnosis in those who underwent colonoscopies with those who did not.

Because these studies are prone to bias, experts prefer randomized trials in which participants are randomly allocated to one of two groups: those who will get intervention and those who will not. These studies then track both groups throughout time to discover whether there are any changes. For colon cancer, which can grow slowly and take years to notice, it has been hard to run these trials.

The researchers plan to continue following individuals for another five years. Because colon malignancies may develop slowly, additional time may assist in improving their findings and reveal greater advantages for colonoscopy screening.

Dr. LaPook on new colonoscopy screening study

Important Caveats

Telling someone to undergo a colonoscopy isn't enough due to the inherent hurdles. Poland, Norway, and Sweden do not test for colorectal cancer via colonoscopies. Colonoscopies were offered to 30% of the 84,000 research participants from these countries. 42% of invited participants had the procedure. Most invitees declined.

“„If you don’t actually have the test, it can’t possibly protect you.- Aasma Shaukat, New York University Grossman School of Medicine gastroenterologist

Time limits the new research. Colitis develops slowly. It takes 10 years or more for polyps to turn malignant. Cancer spreads slowly and kills. Shaukat argues the study's 10-year follow-up isn't long enough to assess colorectal cancer fatalities.

The research colonoscopies ranged in quality. The adenoma detection rate is the number of colonoscopies that find a precancerous polyp, or adenoma, divided by the total number. In the most recent study, more than 30% of the doctors who did surgeries had rates lower than the minimum qualifying rate.

The research acknowledges these limitations in its publication. They believe colonoscopy-by-invitation may have understated its advantages. The researchers will publish data again after 15 years, expecting cancer risk reductions to occur before death risk decreases. Additionally, practitioner quality criteria may have influenced cancer detection.

Shaukat believes the current research should be studied with prior evidence of screening colonoscopies' efficacy. The risk of getting colorectal cancer and dying from it was cut by about 70%, according to a study published in the British Medical Journal in 2014.

Another observational study examined a colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and FIT screening program. A 2018 study in Gastroenterology found that from 2000 to 2015, the program increased screening and cut colorectal cancer cases by 25% and deaths by 52%.

A US randomized controlled experiment compares screening with colonoscopy or FIT in average-risk patients. More data is coming. may believe the latest research isn't definitive. "Colonoscopy isn't dead."

Final Words

According to the CDC, 1 in 5 US individuals between 50 and 75 have never been checked for colorectal cancer. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends many colorectal cancer screening options for those who are uncomfortable with colonoscopies.

It suggests screening with stool tests for blood and/or cancer cells every one to three years; a CT scan of the colon every five years; a flexible sigmoidoscopy every five years; a flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years with yearly stool blood tests; or a colonoscopy every 10 years.

Because younger people are getting colorectal cancer, the task group dropped the recommended screening age from 50 to 45 in 2021. From more than 278,000 patients registered between March 2014 and 2020, 35% of the colonoscopy group obtained one, compared to 55% of the stool test group. Stool testing has found somewhat more malignancies than colonoscopy.

Karan Emery

Author

Karan Emery, an accomplished researcher and leader in health sciences, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals, brings over two decades of experience to the table. Holding a Ph.D. in Pharmaceutical Sciences from Stanford University, Karan's credentials underscore her authority in the field.

With a track record of groundbreaking research and numerous peer-reviewed publications in prestigious journals, Karan's expertise is widely recognized in the scientific community.

Her writing style is characterized by its clarity and meticulous attention to detail, making complex scientific concepts accessible to a broad audience. Apart from her professional endeavors, Karan enjoys cooking, learning about different cultures and languages, watching documentaries, and visiting historical landmarks.

Committed to advancing knowledge and improving health outcomes, Karan Emery continues to make significant contributions to the fields of health, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals.

Daniel James

Reviewer

Daniel James is a distinguished gerontologist, author, and professional coach known for his expertise in health and aging.

With degrees from Georgia Tech and UCLA, including a diploma in gerontology from the University of Boston, Daniel brings over 15 years of experience to his work.

His credentials also include a Professional Coaching Certification, enhancing his credibility in personal development and well-being.

In his free time, Daniel is an avid runner and tennis player, passionate about fitness, wellness, and staying active.

His commitment to improving lives through health education and coaching reflects his passion and dedication in both professional and personal endeavors.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles